Genes Of ‘Sea Aliens’ Stir Up Theory Of Evolution And Offer New Insight Into Origin Of Life On Earth

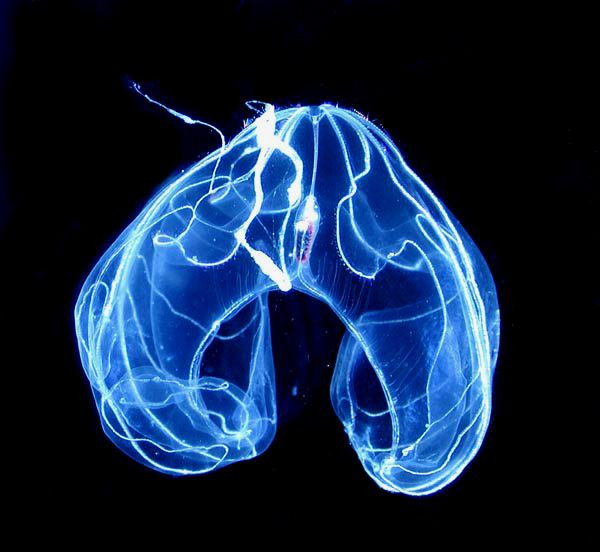

Comb jellies, a widely distributed group of marine animals known as “aliens of the sea,” have caused scientists to reconsider what we know about early evolution.

New research into the genetics of these sea aliens challenges the long-held theory that the animal kingdom sprang from a single ancestor, a title many scientists believe is held by the simple sea sponge. Because comb jellies build a nervous system essentially using their own biological language, scientists said the finding could also point to new ways to study brain diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.

According to a new study published Wednesday in the journal Nature, researchers from the University of Florida in Gainesville found that the little-understood translucent comb jelly, whose scientific name is ctenophores, has a nervous system that's distinct from any other living creature. This suggests that comb jellies evolved independently from the rest of the animal kingdom.

"It's a paradox," Leonid Moroz, a neurobiologist at the university and lead author of the study, told National Geographic. "These are animals with a complex nervous system, but they basically use a completely different chemical language" from every other animal.

By mapping the genes of 10 species of comb jelly, Moroz and his team found that, unlike the rest of us, comb jellies don’t use neurotransmitters -- signaling chemicals like serotonin and dopamine -- found in other animals. Instead, ctenophores developed circuits of neurons that control their motion and behavior.

In other words, the comb jelly, which ranges in size from a few millimeters to 1.5 meters --is a truly alien creature unlike any other animal on Earth. They are distinguished as the largest animals that swims by means of cilia, or “combs.” Some also have the ability to regenerate lost body parts, even their brains.

"It's almost like evolution has given us two different blueprints for building a structure that's very important," biologist Antonis Rokas, of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, who wasn't involved in the study, told The Associated Press. "If your goal is to make a nervous system, it doesn't matter what the parts are in some ways. You could potentially mix and match. The more parts you have, the more solutions."

The cells of early animals could sense their environment and send signals to each other directly. These signals became the raw material from which the brain was formed.

So what sent comb jellies on such a drastically different course from everyone else? Researchers say a parallel evolution occurred some 550 million years ago when comb jellies split off from other animal lineages.

According to this new theory, one lineage led to today’s ctenophores, and the other led to all other animals with nervous systems.

The theory builds on previous work by researchers from the National Institutes of Health in Bethseda, Maryland, who in December, came to a similar conclusion about early evolution. They concluded that comb jellies represent the animal kingdom’s oldest ancestor, not the sea sponge, a finding that continues to spur controversy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.