Google Maps And Crimea: App Doesn't Recognize Russian Takeover

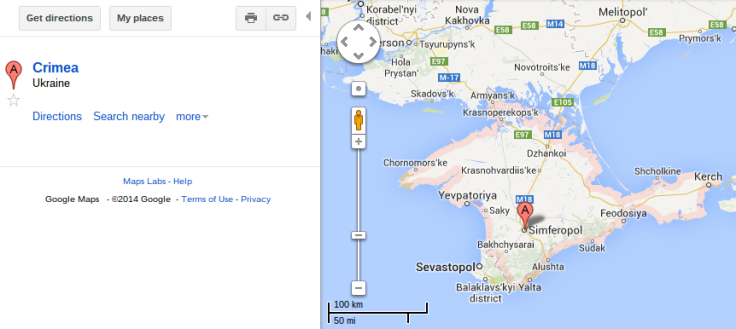

Weeks after Russian troops took over Crimea and the peninsula's residents voted overwhelmingly to join Russia, Google Maps remains unconvinced. Crimea remains part of Ukraine, according to the mapping site, which is the most frequently used smartphone app in the world.

That stance represents a major change for Google (NASDAQ:GOOG), which has refused to take sides in other high-profile conflicts, resorting to simply drawing borders based on the user's location. Thus, when they look at Arunachal Pradesh, a Himalayan border area disputed between China and India, Chinese users see that it's part of their country and Indians that it is part of India. Similarly, users in Arab countries see the Persian Gulf labeled as the Arabian Gulf, long a source of contention between Iran (formerly known as Persia) and its neighbors.

The Crimea decision also stands in contrast to Google Maps' competitors. Microsoft's Bing Maps and the Russian-language version of Wikipedia label Crimea as contested territory between Ukraine and Russia when viewed by users there. And National Geographic issued a statement saying it too would label Ukraine's borders as "contested" following the Russian seizure, although a spokesman explained that the move "does not suggest recognition of the legitimacy of the situation." Yandex, Google's biggest competitor in Russia, now shows Crimea as part of Russia on maps viewed on Russian-language versions of the site, while showing it as part of Ukraine in that country.

Google's position is angering some Russian politicians, one of whom, Anatoly Sidyakin, issued a complaint to the Russian equivalent of the FCC, the Federal Mass Media and Inspection Service, asking it to investigate why Google had not yet changed its borders.

Google's hierarchy may have personal reasons for taking sides on Crimea.

Google co-founder Sergey Brin left Moscow as a child with his family during the collapse of the Soviet Union. He said their emigration was largely due to the anti-Semitism they faced. "I've known for a long time that my father wasn't able to pursue the career he wanted," Brin said in 2007. When then-Russian President Dmitry Medvedev visited Silicon Valley in 2010, he met with Google Chairman Eric Schmidt, but not Brin.

Brin clearly has a critical view of his birthplace. In a 2002 interview with Red Herring, he advised journalists traveling to Russia to "bring a bodyguard." When asked about the geopolitical implications of Russia's energy reserves, Brin then responded critically:

Russia is Nigeria with snow. Do you really want a bunch of criminal cowboys controlling the world's energy supply?

The Washington Post suggested that Google sidestep the Crimea controversy by doing the same thing it does with Arunachal Pradesh. That tactic is not good enough to deal with the ethical dilemma it creates by having two different versions of the world's borders, according to Dr. Harley Balzer, associate professor of government and international affairs at Georgetown University and former executive director of the International Science Foundation.

"It is morally reprehensible to publish a map that recognizes Russia's claim to Crimea when it is against international law," Balzer said. During the Cold War, he noted, American mapmakers diplomatically placed the Baltic states within the Soviet border, while noting that the U.S. State Department did not recognize their annexation.

In this case, Google's decision could help put pressure on Russia, says Balzer. Having one version of Google Maps for the rest of the world and one version for Russia "sets the stage for Planet Putin quite nicely, but I think that it's important for Russians that the rest of the world doesn't buy it. If maps here indicate that it's a disputed territory, then Russia ought to do the same."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.