'The Great Gatsby' Movie Review: Look Here, Old Sport

Baz Luhrmann’s much-anticipated adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” has roared into theaters, and much like a traveling circus descending upon a town, not everyone’s going to happy about it. But anyone familiar with Luhrmann’s previous films (“Romeo and Juliet,” “Moulin Rouge”) has a pretty good idea of what to expect. Furthermore, you may also find that “The Great Gatsby” is more enjoyable than you imagined.

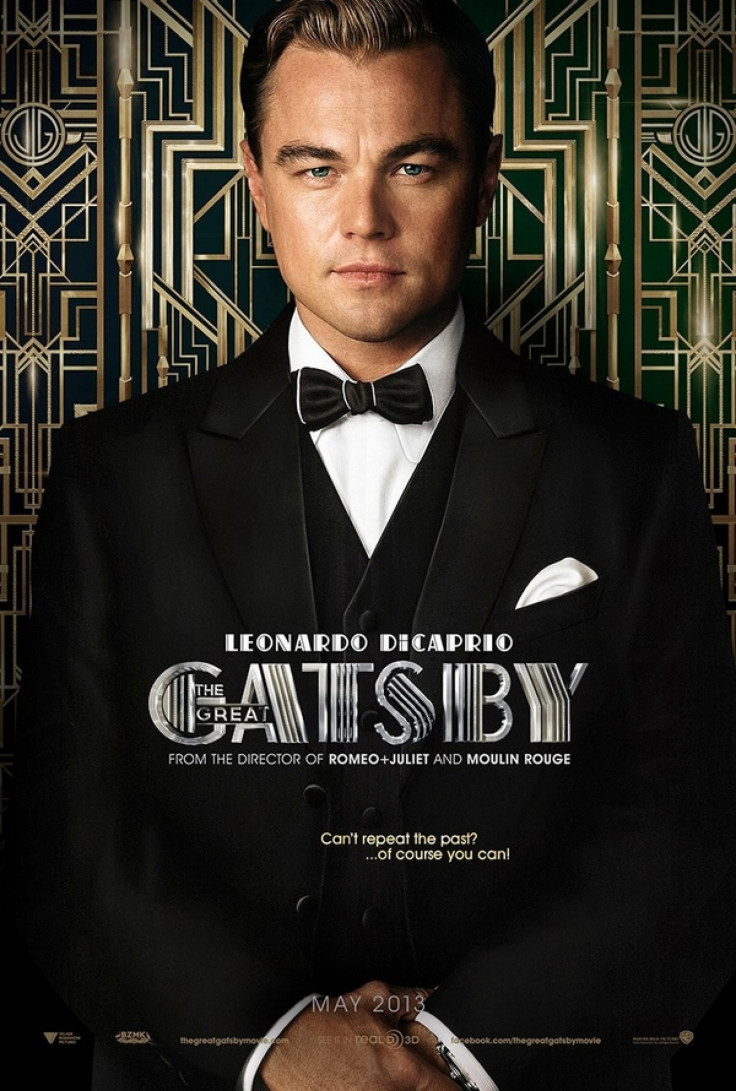

Tobey Maguire came out of early retirement to to play Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald’s narrator and recent transplant to West Egg, Long Island, where he rents a house next door to the mysterious, charming and incredibly rich Jay Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio). Nick’s cousin, Daisy Buchanan (Carey Mulligan), and her husband Tom (Joel Edgerton) live across the bay in East Egg, with the old money. Nick eagerly accepts the invitation to be part of this decadent, wild-partying world, and quickly becomes a witting pawn in Gatsby’s single-minded efforts to reclaim Daisy, who was once his girl.

Luhrmann’s adaptation is less an interpretation of “The Great Gatsby” than a celebration of its sensual pleasures -- his “Gatsby” is larger than life, with a hip-hop heavy soundtrack produced by Jay-Z. Presenting it in 3-D doesn’t serve the story at all, but maybe that’s the point, as the device seems to be a cue that spectacle is what’s important here. The effects add a harmless layer of underbelly to the absurdly extravagant party scenes, but in smaller, quieter moments, it’s an unwelcome distraction. When the terminally gobsmacked Maguire is leaping out at you from the screen, he feels even harder to reach.

I’ve always suspected DiCaprio might be just a touch overrated. Now I am not so sure. As Jay Gatsby, DiCaprio is permitted to be dashing, and is completely at ease with every facet of his character, both when Gatsby is in complete control of his kingdom, and when he is painfully vulnerable (more often.) Luhrmann is more sympathetic to Jay than Fitzgerald was: Although we are never quite permitted to forget that his generosity and impeccable manners are means to the ultimate end of stealing another man’s wife, DiCaprio gives him a warmth that always feels genuine, even when his chemistry with Mulligan’s Daisy does not. Indeed, DiCaprio doesn’t get the help from his co-stars and the script that his performance deserves: You come away with the sense that his delivery would be no different if he were alone in front of a green screen. And he seems to be working overtime to convey Gatsby’s sense of determined desperation that his lines don’t always get across effectively. His eyes tell the part of the story that was lost on the way from the page to the screen.

Luhrmann’s unbalanced preservation of Fitzgerald’s prose could alienate the novelist’s devotees, and many may wish that he had made up his mind one way or the other about how faithful he would be. Much of Maguire’s voiceover narration is taken verbatim from the novel, as is a good portion of the dialogue, and this word-for-word adherence makes the sometimes inexplicable deviations and embellishments feel more glaringly out of step. Luhrmann’s Jazz-Age Queens resembles a postapocalyptic wasteland, and an exaggerated visual in an early scene feels rather ridiculous. On Nick’s first visit to the Buchanan home, a breeze blows through French windows in the room where Daisy and Jordan Baker (Elizabeth Debicki) lounge. In the book, the breeze “blew curtains in at one end and out the other like pale flags.” In the movie, it is more like a tempest. Some key scenes -- particularly those that involve the tense dynamic between, Daisy, Tom and Gatsby -- feel a bit rushed, as though the director is impatient to get to the next big spectacle.

But we can’t forget that Luhrmann is under no contract to elevate the literary merits of his source material. Luhrmann is a big, loud, colorful filmmaker and he delivers a big, loud, colorful “Gatsby.” It’s easy to presume that the novel’s preoccupation with all things lavish was the main attraction for the filmmaker, and he certainly delivers excess in spades -- often to the point of obscenity. Gatsby’s wild parties have the exuberance of a Broadway production on amphetamines: If you don’t actually feel like you are there, you will wish you were, at least for a bit. The alcohol-soaked scenery is meant to be taken at face value. These are people (save Gatsby, of course) who can’t bear to be without a drink in their hands: Sometimes, it’s a blast, and other times, terrible things can and do happen. But unless you count the framing device -- Nick narrates from a sanitarium, and alcoholism appears to be part of the problem -- Luhrmann presents this without much caution or commentary, even though there’s always a bottle in his sights.

What little class commentary Luhrmann offers is all in the visuals. Although the performance itself is unremarkable, Isla Fisher deserves credit for taking on a gaudy and unappealing Myrtle, Tom’s mistress, who is cartoonishly overdone in cheap-looking clothes and pounds of unflattering makeup. Jason Clarke (“Zero Dark Thirty”) is nearly unrecognizable as Myrtle’s husband, Wilson, but mostly because, as an auto mechanic, he’s perpetually covered in filth. From the fire escape of a wild party at Myrtle’s upper Manhattan mistress pad, Nick surveys the lives of apartment dwellers packed into a building a fraction of the size of Gatsby’s estate, briefly studying through the windows their curious existence as someone might gaze at an aquarium.

Fitzgerald’s novel has enjoyed a great deal of renewed attention as a result of the movie. But even before the film, “The Great Gatsby’s” status as an American cultural artifact is unassailable, whether or not the novel is as important as suburban high-school English teachers insist. For better or worse, Luhrmann’s interpretation leaves a new imprint on the legacy of “The Great Gatsby” that won’t be easy to forget. Now that he’s brought together Jay Gatsby and Jay-Z, can they ever be separated?

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.