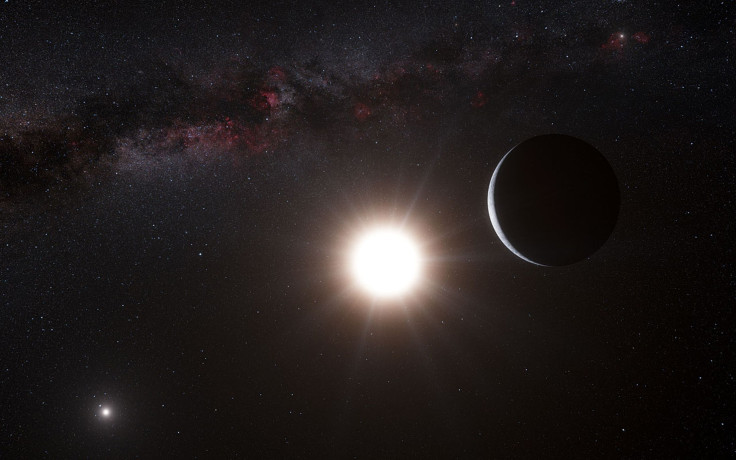

Ground-Based Telescope Helps Detect ‘Super-Earth’ Exoplanet Transiting Sun-Like Star For First Time

Astronomers have used a ground-based telescope for the first time to detect a “super-Earth” exoplanet while it was transiting a nearby sun-like star. The latest findings are expected to help scientists characterize many small planets that are likely to be discovered by future space missions over the next few years.

The scientists used the 2.5-meter Nordic Optical Telescope on the island of La Palma in Spain to discover the exoplanet, dubbed “55 Cancri e.” The exoplanet’s star, called “55 Cancri,” is only 40 light-years away from Earth, and is visible to the naked eye, the researchers said in a study, set to be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“Our observations show that we can detect the transits of small planets around Sun-like stars using ground-based telescopes,” Ernst de Mooij of Queen's University Belfast in the United Kingdom and the study’s lead author, said in a statement.

During its transit, "55 Cancri e" crosses the star and blocks a small fraction of its starlight, dimming the star by 0.05 percent for nearly two hours, helping scientists determine that the planet is about twice the size of Earth, or 16,000 miles in diameter.

“This is especially important because upcoming space missions such as TESS and PLATO should find many small planets around bright stars and we will want to follow up the discoveries with ground-based instruments,” de Mooij said.

Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is a space telescope that is part of NASA’s 2017 Explorer program, which is designed to search for exoplanets. PLATO is a European Space Agency observatory, which is planned to be launched in 2024 in search of transiting terrestrial planets.

According to astronomers, the planet "55 Cancri e" is about eight times as large as Earth, and is the innermost of five planets in the system. And, thanks to its proximity to the host star, the planet is not suitable to support any known life form with daytime temperatures of over 3,100 degrees Fahrenheit, which is hot enough to melt metal.

“With this result we are also closing in on the detection of the atmospheres of small planets with ground-based telescopes,” Mercedes Lopez-Morales of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the study’s co-author, said in the statement. “We are slowly paving the way toward the detection of bio-signatures in Earth-like planets around nearby stars.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.