Hacking The Hookup App: Can We Save Online Dating With More Data?

In 2014, 37-year-old former Lehman Brothers analyst Cliff Lerner thought he’d found the perfect hack for online dating. He created an app called Mutually that would connect people by the act of mutual swiping -- like Tinder -- but he added a twist: It also recommended date spots, powered by Yelp reviews.

Helping close the deal, right, bro?

Mutually didn’t take off, but like a lot of failed ventures, the app inventor learned from it. “It became very clear that the real opportunity was to build a product that catered to women,” Lerner said. “Our users asked for something that would help them handle men who were hostile and offensive.”

Hence, Lerner’s new baby, The Grade -- an app that exposes how fast and often people respond to messages and the quality of these texts. The Grade scans users’ app use and assigns a letter-grade for all to see.

Newcomers have mimicked Tinder (or the older “Hot Or Not”) by putting physical appearance at the forefront of dating technologies, emphasizing photos on profiles and allowing people to swipe through picture cards on their smartphone. But now they’re also employing data on behavior, which is meant to further empower users on the other side of the romance equation, arming them with more relevant info about whether to swipe right to indicate interest.

Earlier this week, Bumble, an app launched by 20-something Tinder co-founder Whitney Wolfe that differentiates itself by allowing only women to initiate conversations, announced its own verification system. The app will soon grant checkmarks (well, bumblebees) to users who maintain a quick response time and message ratio, complete their profiles and have never been reported for inappropriate behavior.

“Bumble is like the Bernie Sanders of dating apps. He ain’t gonna be the president, but he’s bringing the conversation to the forefront,” said dating app analyst and blogger David Evans. “There’s no Federal Trade Commission best practices on what is a good person on the Internet.”

Vetting The Hookup

While new dating and hookup apps have used Facebook as a quick and free way to vet users’ identity (rather than request other proofs of authenticity), they still struggle with a simple way to monitor behavior -- without discouraging use -- as they tap into an industry valued at $2.2 billion.

For now, Tinder boasts “verified accounts” for celebrities only. Now competitor apps are beginning to experiment with their own systems for notable people of a different accord. After reaching about 500,000 members in June, Bumble cofounder Wolfe said her team began to plan ways to keep the growth moving forward and also maintain positivity on the network.

“Our data suggested that we’re really doing a great job of creating results, lots of two-way conversations. We were enamored with that data. When you see something like that, you want to preserve it,” Wolfe said. “Our vision for Bumble was to keep it the confident and fun place to meet forever and always.”

In the coming update, Bumble will introduce “VIBee” -- a system that rewards users with a badge if they keep good behavior on the app. The algorithm is secret, but Wolfe said that it works to prevent users from nonstop swiping, left or right, and from spam messaging. For the first round, they’re initiating from 10 percent to 15 percent of users, but the app will frequently bring in more.

This type of vetting is not a brand-new concept for dating sites. Juggernaut site OkCupid has a red-yellow-green light system based on response time, for example. But new apps like Bumble and The Grade, partially piggybacking off "Tinder hate,” are digging more into user data as a way to increase transparency.

“We’re not saying we’re going to take on Tinder. We don’t want every user. All of our users are going to be high quality and accountable for their behavior. A lot of people will be kicked off,” Lerner said. With about 100,000 downloads of The Grade so far, approximately 1,000 have been expelled and 2,000 are in danger of “failing.”

The Grade chose to employ a system that was heavily data driven. The app will analyze message quality, including length, spelling mistakes, slang and hostile words. But like Facebook’s reporting algorithm, that type of system can fall victim to mistakes.

“Certain phrases and words can be very offensive in certain contexts but appropriate in others,” Lerner said. Users can then appeal to The Grade, but that requires going beyond the machine and having more employees to respond to user feedback.

Is Exclusivity Sustainable?

Lerner currently employs a team of seven men, and Wolfe’s Bumble has about six full-time workers -- all women. The Grade is staying afloat with financial support from other ventures. Bumble has an undisclosed amount of funding, fueled mainly by Russian billionaire Andrey Andreev, Time reports.

Neither app has incorporated monetizing strategies yet. Both founders say that, for now, they are focused on user growth. The same process of treading lightly has been followed by social network Facebook and Twitter, and now it’s begun on Instagram and Snapchat. As to the dating app world’s “golden child,” Tinder launched its premium service in March and had its first paid ad in April.

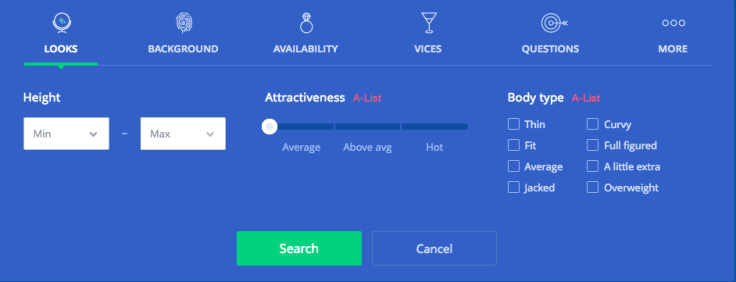

Older legacy services -- ones that start as a website and then build an app -- have pulled in revenue from exclusive services. For example, market-leading dating site Match.com and OkCupid both have subscription models and are owned by Los Angeles-based IAC/InterActiveCorp, along with Tinder. Users can also pay for one-off services, such as promoting their listings or paying for access to chat with highly desired members, to rank other users by attractiveness and to sort by body type.

While these other companies may be older and more sophisticated in their payment models, with an army of loyal users, the conversation has evidently changed to include more about safety. “All the focus was on user acquisition and revenue. They didn’t put these blatant efforts into advanced monitoring and safety,” said Evans, who has been blogging and consulting for online dating companies since 2002.

But the real problem for these apps is building enough support while leaving the online creeps behind. Could exposing people turn more of them off?

“Anytime you implement any sort of friction through a technology by limiting communication, your sign-ups can really, really suffer. You can get into a tailspin,” Evans said. “The investor rate-of-return [for a dating app] is worse than the effectiveness of a dating site algorithm.”

As to eventually pulling in the revenue, Evans proposes a system that could charge users a fee for a verified endorsement of character. Dating app Hinge, a popular competitor of Tinder, has a similar system that's free; it shows you what Facebook friends you have in common. In April, Tinder added the same feature. But that still requires a user to reach out to someone else: a potentially awkward and time-consuming situation for #GenerationTinder.

But it’s not going to dissuade us from building something that is changing the world. #GenerationTinder

— Tinder (@Tinder) August 11, 2015Lulu launched in 2011 as a website where people could submit reviews of men. The app's not as text heavy as Yelp; rather, it is a rating system of numbers and hashtag phrases such as #KissableLips and #WorkInProgress. Some have classified it as a revenge site because the app struggles to capture data on what happens after you connect, while other businesses focus on the in-app experience.

That, once again, requires more human feedback. “We want to see that you get out the door safely. We’re not there to babysit you,” Wolfe said. “But let’s kick this connection off in a two-way conversation.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.