Haiti Elections 2015: Ahead Of Presidential Vote, Officials Look To Avoid Turmoil In High-Stakes Political Contest

More than two months after allegations of fraud and scattered violence marred Haiti’s legislative elections, voters were set to return to the polls Sunday to decide on the country’s leadership. This time around, the elections, encompassing the first round of a presidential vote, will give the Caribbean nation another opportunity to test its fragile democracy and usher the government out of a festering political crisis.

Haiti’s electoral council is scrambling to crack down on corruption and fix the logistical mishaps that plagued the Aug. 9 legislative elections, in which only 18 percent of the eligible population came out to vote. But observers are anything but certain about whether this higher-stakes vote will avoid the same pitfalls. If the elections fall short of the free and fair process everyone is hoping for, another five years of political turmoil could be on the horizon for a country that remains in desperate need of stability.

“If you see a repeat of what happened in August, it’s going to be very difficult to see the next government forming with any success,” said Jake Johnston, a Haiti analyst and research associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington-based think tank.

Like the August elections, this weekend’s vote will be one of massive proportions. Voters will decide runoff races for 139 legislative seats and hundreds more municipal positions across the country. Most of those seats have been either vacant or occupied by political appointees since the previous officials’ terms expired. Legislative elections had been postponed since 2011 while President Michel Martelly and legislators wrangled over electoral laws, prompting a wave of protests over the delays. Only 10 senators remain in office, and Martelly has effectively ruled by decree since early this year.

Fifty-four candidates are also vying for the presidency in a vote that will very likely go to a final runoff round, scheduled for December. Jude Celestin, a center-left candidate and the former head of the government’s construction ministry who ran for the presidency in 2010, has led the pack in recent polls. Other high-profile candidates include former Sen. Moise Jean-Charles, a staunch critic of Martelly, and Maryse Narcisse of the leftist Fanmi Lavalas party, which had a series of landslide election victories in the early 2000s but has since been beset by internal divisions. Haiti’s constitution prohibits presidents from being elected for two consecutive terms, so Martelly is not allowed to run this year.

An Election Day free of complications would be critical to bringing in a stable government that can steer economic growth and robust development during the next several years. Around 60 percent of the population lives under the poverty line, and Haiti remains in a slow recovery in the wake of its massive 2010 earthquake.

The meager 18 percent turnout for Haiti’s August legislative elections was even lower than the 23 percent turnout for the country’s 2010 presidential vote, which took place amid the chaos of a cholera breakout and other challenges associated with the earthquake. Scattered reports of violence and voter intimidation clouded the August vote, and the Haitian National Police, which was tasked with ensuring security for the elections, faced accusations of neglect by human-rights groups.

“The Haitian National Police were like observers,” said Pierre Esperance, executive director of the National Human Rights Defense Network, an advocacy group based in Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince. “They observed what happened, but they didn’t provide security.” The electoral council disqualified 14 candidates over violent disruptions in August, but Esperance said several others involved in the disturbances went unpunished.

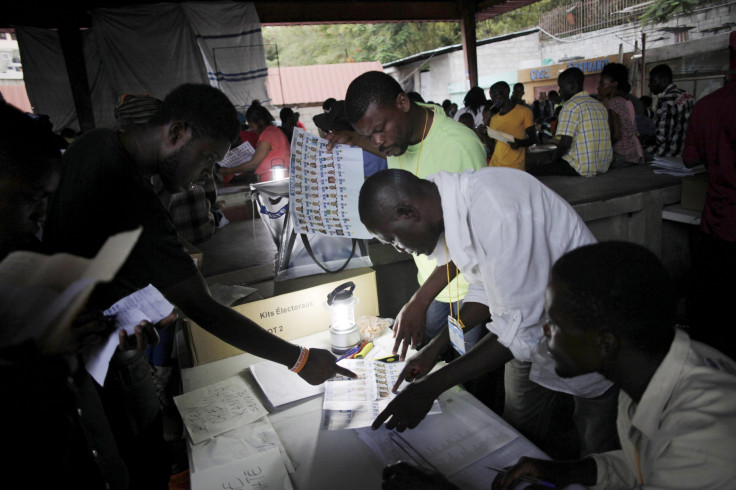

Other reports detailed a variety of logistical fiascos. In some cases, ballots were lost or delivered late, and in other instances, voters arrived at their local polling stations only to find them closed. Many political party monitors also received accreditation passes late, resulting in an uneven supervision process and a flurry of charges of unfairness. Those irregularities prompted the electoral council to announce a rerun of first-round elections in 25 of 119 constituencies.

The electoral council has taken some steps to alleviate some of those problems, including issuing accreditation passes ahead of time and adding more workers to help direct voters to the proper polling centers. But logistical improvements alone may not be enough to ward off disruptions, analysts said.

Certain decisions made by the electoral council undermine confidence in Sunday’s elections, said Brian Concannon Jr., executive director for the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, a Boston-based human-rights group that works with a number of Haitian advocacy organizations. After the August elections, the council determined that as long as 70 percent of a municipality’s ballots could be counted, it could avoid having to rerun the vote.

“That’s kind of a crushingly low barrier for success,” Concannon said. The council hasn’t taken any steps to raise that threshold for this round of voting, which he said leaves incentives for factions to disrupt voting in some areas to tip the figures in their favor. There are no international standards for what proportion of ballots must be included in the final tally.

Observers also noted the council didn’t require do-overs for several constituencies where the ballot count fell below the 70 percent threshold, adding to criticisms over the council’s credibility as an election authority.

The U.S. has long considered Haiti a policy priority because of its geographical proximity, and it voiced concern over the country’s political troubles. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry visited Port-au-Prince Oct. 6 to show his support for the electoral process, emphasizing the vote must take place as scheduled and that violence should not be tolerated.

But Kerry’s visit dashed some hopes that the U.S. would demand higher standards for Haiti’s election, particularly as he declined to address some of the electoral council’s decisions. “Most people who responded to that speech saw it as a sign the U.S. was not going to do anything to force fundamental changes,” Concannon said.

The U.S. has been one of the main benefactors of the election, contributing about $30 million to a multidonor fund managed by the United Nations Development Program that totals around $72 million. The U.N. has doled out those funds to support the electoral council’s operations and civil-society groups’ activities, including voter education programs and political debates. Haiti’s government has contributed $10 million to fund political parties and the campaigning process.

“This is an extremely expensive electoral process, and the impression on the ground is that it’s hard to see where the money was spent,” said the Center for Economic and Policy Research’s Johnston. Haitian human-rights organizations reported that polling locations were small and cramped to accommodate voters, booth partitions were made of flimsy cardboard and ballot boxes sometimes consisted of transparent plastic bags.

Despite the electoral council’s pledge that it had learned from the mistakes of the August vote, many Haitians, including Esperance of the National Human Rights Defense Network, aren’t placing their bets on major improvements this time around. There haven’t been any assurances that police would provide better security, and there was still no transparency on some of the council’s controversial double standards in the legislative vote, he said.

“Anything can happen on Oct. 25,” Esperance said. “I hope it will be better [than the August elections], but at the same time I will say we are very pessimistic.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.