'Hear My Voice, Alexander Graham Bell': Smithsonian Releases 128-Year-Old Recording Of The Telephone Inventor [AUDIO]

American history is full of memorable quotes and speeches, but until recently the oldest audio recorded was captured in 1888 on a phonograph invented earlier that year by Thomas Edison. Thanks to new technology, however, physicists have been able to recreate and convert even older recordings once thought "lost to history" into playable audio recordings, which is how the Smithsonian was able to salvage the voice of Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, from an 1885 recording made on a rare experimental phonograph.

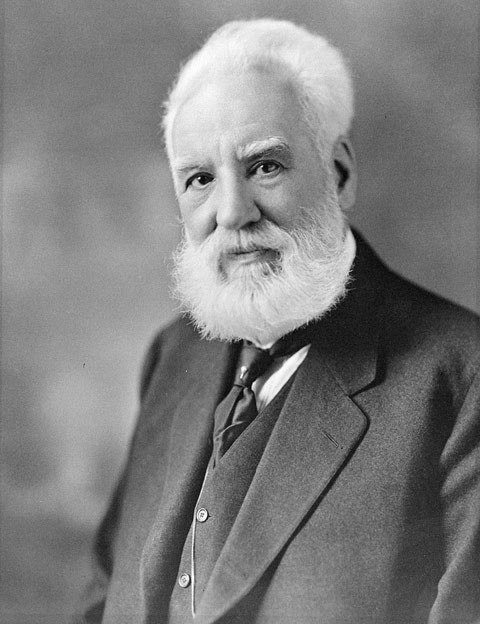

Bell, a Scottish-born engineer, scientist and teacher of the deaf, was passionate about language and sound from an early age. His brother, father and grandfather all worked with elocution and speech in some capacity, and, as a boy, he would entertain his family guests with “voice tricks” and sound mimicry, similar to a ventriloquist.

Bell, who later moved from Edinburgh to London and Canada before landing in Boston in 1871, created an audio recording on a wax and cardboard disc on April 15, 1885. He had experimented with sound at his Volta Laboratory in Washington between 1880 and 1886, hoping to one-up his rival, Thomas Edison, in improving the recording process -- Edison used embossed foil, while Bell tested a variety of materials, including paper, plaster, metal, wax and cardboard. Until recent audio extraction technology came along, many of Bell’s 4- to 14-inch discs were thought to be “mute artifacts.”

This is the first audio recovered from the inventor, in which you can clearly hear Bell say, “In witness whereof -- hear my voice, Alexander Graham Bell.”

The audio was recovered by a team of scholars including Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory physicist Carl Haber, National Museum of American History curator Carlene Stephens and Library of Congress digital conversion specialist Peter Alyea.

The Smithsonian, which announced its collection of audio recordings from Bell’s Volta Lab in December 2011, owns more than 400 discs and cylinders used by Bell in his attempts to record sound. Bell was a member of the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, and he had donated a vast trove of his laboratory materials to the museum up until his death in 1922.

The new sound extraction process, called optical scanning technology, can be used to unlock even more of Bell’s old phonographs produced by the Volta Laboratory Association and Bureau. Since many of the collected recordings are very fragile due to their age and experimental nature, optical scanning is a noninvasive way to extract audio from these delicate artifacts. After scanning the discs or cylinders and reconstructing the objects into digital maps, scientists then carefully remove any evidence of wear or tear on the records -- filling in the blanks, so to speak. The finished digital map is then run through a piece of software that recreates the motion of a stylus moving through the grooves of the disc or cylinder, which reproduces the audio content into a standard sound file.

Alexander Graham Bell biographer Charlotte Gray described what it was like to finally hear the voice of the man she had studied for so long.

“In that ringing declaration, I heard the clear diction of a man whose father, Alexander Melville Bell, had been a renowned elocution teacher (and perhaps the model for the imperious Prof. Henry Higgins, in George Bernard Shaw’s "Pygmalion"; Shaw acknowledged Bell in his preface to the play),” Gray said. “I heard, too, the deliberate enunciation of a devoted husband whose deaf wife, Mabel, was dependent on lip reading. And true to his granddaughter’s word, the intonation of the British Isles was unmistakable in Bell’s speech. The voice is vigorous and forthright, as was the inventor, at last speaking to us across the years.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.