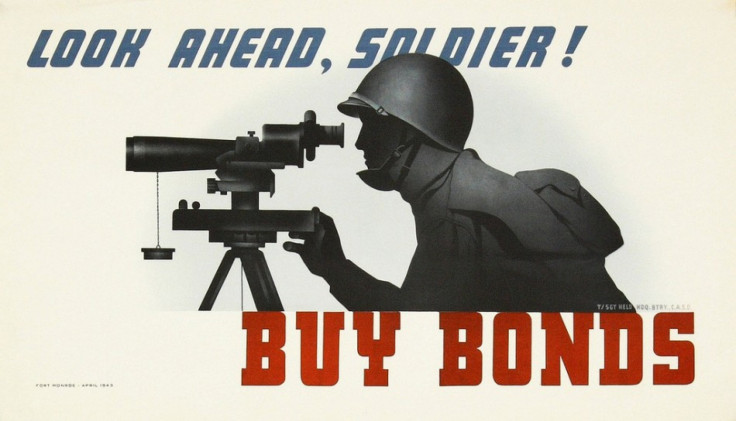

How Low Can They Go? Forecaster Sees T-note Yield Falling To 1.32%

Look out below: this bond market's bull run has lots more room to run

Oh what a difference 10 weeks makes.

Around the third week of March, when yields on benchmark 10-year Treasury notes spiked close to 2.4 percent -- making instant losers of traders who had flocked into the instruments for their perceived value as the world's premier safe-haven -- the chatter on Wall Street bond desks was that Treasury yields had hit a floor and had nowhere to go but up.

But after Friday's ugly U.S. jobs report, plus a catastrophic U.K. manufacturing activity reading, yields on 10-year notes dropped as low as 1.4453 percent, blowing past predictions of market watchers who earlier in the week, when yields were closer to 1.7 percent had suggested the instruments would bounce off a 1.5 percent floor.

That fall in yields has followed high volatility the past few days arising from Greece's worsening political situation, highly disappointing economic data prints in the U.S. and China and, most prominently, a surprise banking crisis in Spain.

Now comes Lawrence Dyer, a New York-based rates strategist for British giant bank HSBC with a whopper of a prediction that lowers the limbo pole nearly to the ground: in his view, 10-year notes should soon fall to 1.32 percent or lower.

Dyer's model takes into account the fact that investors are aggressively pursuing flight-to-safety strategies that are leading to a bull-flattening of the yield curve, with yields on longer-dated securities falling faster than those on shorter-term maturity instruments. In a flight-to-safety situation like the one being experienced by world markets at the moment, traders first snap up one-year and two-year Treasury bills before dipping into five- and 10-year notes. The fall in what is normally referred to as front end bills also normally tracks a similar movement in rates for ultra short-term maturities, like overnight lending, or repo, contracts. But, as Dyer sees it, the market seems to have had its fill of those bonds and front end yields have limited room to fall unless and until repo (and Treasury bills) fall as well.

Dyer then extrapolates what premium investors might demand on yields for Treasury bonds with maturities over two years that, again, he does not think will move further down. Assuming returns on 0.27 percent on two-year notes, he believes investors will demand about 10 additional basis points for each additional year it takes for their securities to mature, when moving from buying two-year to five-year bonds. So, five-year bonds should settle around a yield of 0.57 percent. They were yielding 0.6139 percent near midday Friday. Investors will demand a higher premium -- Dyer assumes 15 basis points per year -- to move from five-year to 10-year notes. That's 75 basis points, which added to 0.57 percent, results in a 1.32 percent yield.

Dyer's model has a somewhat finger in the wind quality to it: it assumes premiums based on data from Japanese bond auctions over the past five years, which are arguably not comparable to the U.S. situation, and ignores the puzzling fact that three-year bills are trading out-of-sync with the rest of the Treasury curve. Yet it is likely to be a foreboding of aggressively low predictions others are sure to make on the direction of U.S. interest rates.

Indeed, Dyer might revise the prediction based on his own model soon. In the time it took to write this article, yields on 10-year Treasuries stabilized around 1.48 percent. But two-year bills, the reference security used to predict where others will go, dropped to 0.2421 percent.

Look out below.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.