Hurricane Irene New York: Top 5 Dangers of a Hurricane in the City

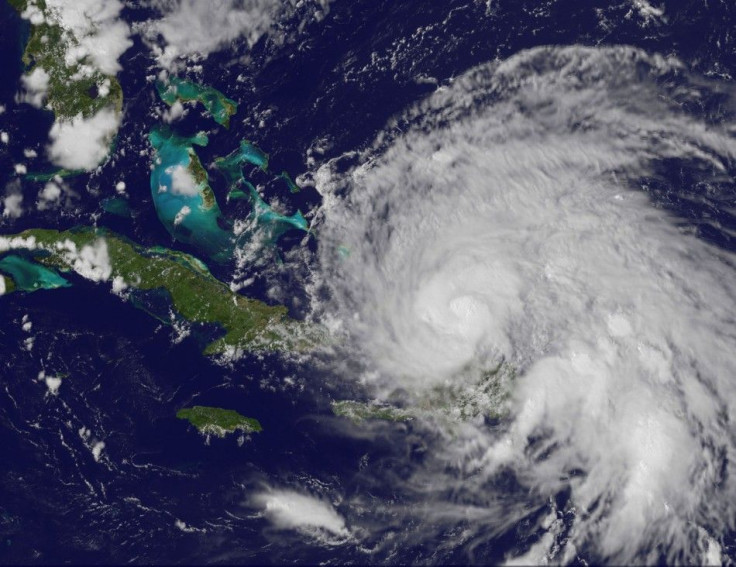

If Hurricane Irene keeps to its projected path, a region unaccustomed to natural disasters may experience two in a single week. The earthquake on Tuesday -- which was centered in Mineral, Va., and sent tremors up and down the Eastern Seaboard -- caused no measurable damage in New York, but if Irene hits the region later this week, it will be a very different story.

Even if Irene reaches New York as a weakened Category 1 or Category 2 hurricane, it could still wreak considerable havoc because the city is simply not prepared to handle such storms the way Florida or the Gulf Coast are. In a worst-case scenario, here are the top five threats New York City would face from a major hurricane.

1. Storm surge

The single biggest effect New York City would see from a major hurricane is the storm surge. This is the term for water pushed toward the shore by high winds, and it can rise many feet above sea level and inundate entire neighborhoods. In the New England Hurricane of 1938, the storm surge from the East River flooded three blocks of Manhattan, even though the center of the hurricane was many miles away, pummeling eastern Long Island. The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane of 1821 made landfall in the city itself -- in Jamaica Bay, Queens -- and the 13-foot surge inundated more than a mile of Manhattan from Battery Park to Canal Street.

Storm surges can be catastrophic even in the best-protected cities -- just look at New Orleans when the levees failed. While a Katrina-like scenario is unlikely in New York, a smaller surge could still be deadly because of the structure of New York's waterways. New York Harbor is narrow, which means that water rushing northward from the storm surge, with nowhere to go, would build up very high -- as high as 30 feet, or the third floor of some buildings, according to past warnings from the city's Office of Emergency Management. According to an evacuation map posted on the city's official Web site, aside from Lower Manhattan, many low-lying parts of the other four boroughs would also be at risk, including LaGuardia Airport and J.F.K. Airport, which are located right by Flushing Bay and Jamaica Bay, respectively. All of this would be compounded if the storm surge happened at high tide.

2. Debris everywhere

Many of the effects of high winds on infrastructure are obvious: downed trees and other debris cluttering the streets, downed power lines cutting electricity to buildings and live wires creating hazards for pedestrians. But in a city like New York, hurricane-force winds could break windows en masse, especially in the taller buildings that would bear the brunt of powerful gusts that occur at higher elevations, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2010. In a worst-case scenario, this could become a scene out of an apocalyptic movie, in which the canyons of Manhattan could magnify the winds and would be a deadly place for anyone caught beneath the raining glass. And that's not even considering the billions of dollars it would take to clean up the city afterward, and the long-term economic impact of those costs.

3. Goodbye, subways

Every New Yorker has seen how messy subway stations get in heavy rain: dirty puddles form on the platforms, water streams from openings in the ceiling onto the tracks, and trains are frequently delayed. Now imagine even heavier rain, plus a storm surge that sent water from the rivers and harbors crashing into the stations through the stairwells, ceilings and tunnels. It would not even take a worst-case scenario to bring the entire New York City public transportation system to a standstill. In the short term, this would eliminate any chance of last-minute evacuations; in the long term, it could extend the economic damage of a hurricane even beyond when office buildings reopened. If the subways were flooded with salt water rather than just rainwater, the salt would corrode the switches and cripple the system for months or years, and disable much of the communications infrastructure in Lower Manhattan, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2010 based on an interview with Nicholas Coch, a coastal geology professor at Queens College.

4. Economic paralysis

The area of New York most likely to be affected by a storm surge is also the area where the bulk of the city's economic activity is centered. The Financial District, for example, could be inundated by storm surges from the East River, the Hudson River and the New York Harbor alike. The 1938 hurricane flooded all of Lower Manhattan south of Canal Street, but the damage was limited by the fact that the area was not highly built up at the time. Today, not only is it full of people who could be killed by a storm surge, but it is also the epicenter of the city, national, and international financial systems.

Residents don't necessarily understand how many days and weeks after a hurricane that their lives will be completely changed, Scott Mandia, a physical sciences professor at Suffolk County Community College on Long Island, told National Geographic News in 2006. People who live away from the water think a hurricane will mean one day away from work, then back to normal. There will be an economic shutdown for a few weeks, if not a month. He was referring to the impact of a hurricane on Long Island, but the impact on the Financial District would be even worse. A big storm surge could paralyze that part of the city for weeks, depending on how severe the flooding was, how quickly the water receded and how much infrastructural damage it left behind, and the consequences of that would be far greater than just lost wages.

5. Difficult to evacuate

If New York remains in Hurricane Irene's path, officials would likely order the evacuation of the most vulnerable areas -- that is, those most likely to be hit by the storm surge. But evacuations are difficult to carry out under the best of circumstances, both because many people are reluctant to leave their homes and because of traffic gridlock as thousands of people try to get out at once, and New York is far from the best of circumstances. The first problem is the sheer size of its population: evacuating more than eight million people on short notice is an impossible task. The second is the location: on an island, escape routes are inherently limited. Only so many vehicles can cross Manhattan's bridges and tunnels at once, and in the event of a hurricane, one thing New York will not have is time.

Hurricanes can change course very quickly, and even a slight shift can threaten areas far from the projected path. Accurate predictions become even more difficult once a hurricane moves north of the Carolinas, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, because the storms begin to move faster and wind patterns can easily redirect them. The New England Hurricane of 1938 struck with just four hours' notice, and hundreds of people were killed. The NOAA Web site notes that the overwhelming majority of lethal hurricanes occurred before hurricane prediction reached levels necessary to adequately serve the public. Of course, meteorologists' predictive capabilities have increased tremendously over the years, but in the Northeast, the problem remains serious because of the combination of less reliable predictions and more time required for a successful evacuation.

In other words, in order to evacuate New York's extremely dense population through a limited bridge and tunnel system, the evacuation would have to begin significantly earlier than it would in the Southeast or along the Gulf Coast, where populations are less dense and escape routes more plentiful. But because of the difficulties in predicting when and where hurricanes will strike in the Northeast, New York most likely would not be able to begin an evacuation until later than the Southeast or Gulf Coast could. Even worse, because winds usually pick up well before the center of a hurricane hits, time to evacuate could be even more severely limited.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.