Icy Jets from Saturn’s Moon Influences its Chemical Composition: NASA

Researchers have found that geyser-like icy jets released by Saturn's moon, Enceladus, strongly influences the chemical composition of its parent planet.

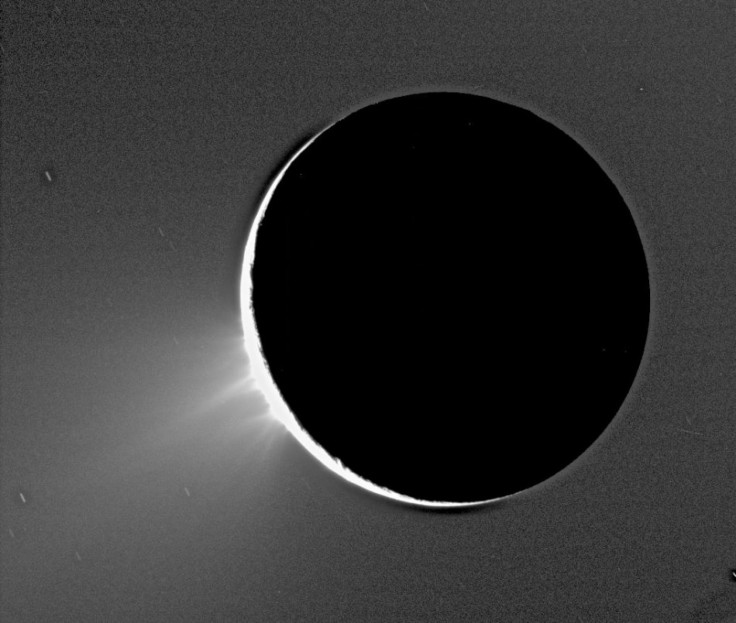

These dramatic plumes of water vapor and ice was first observed by NASA's Cassini spacecraft in 2005.

It possesses simple organic particles and may house liquid water beneath its surface. Its geyser-like jets create a gigantic halo of ice, dust and gas around Enceladus that helps feed Saturn's E ring.

In June, the European Space Agency announced that its Herschel Space Observatory, which has important NASA contributions, had found a huge donut-shaped cloud, or torus, of water vapor created by Enceladus encircling Saturn.

The torus is more than 373,000 miles across and about 37,000 miles thick. It appears to be the source of water in Saturn's upper atmosphere.

Though it is enormous, the cloud had not been seen before because water vapor is transparent at most visible wavelengths of light. But Herschel could see the cloud with its infrared detectors.

Herschel is providing dramatic new information about everything from planets in our own solar system to galaxies billions of light-years away, stated Paul Goldsmith, the NASA Herschel project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

The discovery of the torus around Saturn did not come as a complete surprise. NASA's Voyager and Hubble missions had given scientists hints of the existence of water-bearing clouds around Saturn.

Then in 1997, the European Space Agency's Infrared Space Observatory confirmed the presence of water in Saturn's upper atmosphere. NASA's Submillimeter Wave Astronomy Satellite also observed water emission from Saturn at far-infrared wavelengths in 1999.

While a small amount of gaseous water is locked in the warm, lower layers of Saturn's atmosphere, it can't rise to the colder and higher levels. To get to the upper atmosphere, water molecules must be entering Saturn's atmosphere from somewhere in space. These were the mysteries that remained unanswered till now.

The answer came by combining Herschel's observations of the giant cloud of water vapor created by Enceladus' plumes with computer models that researchers had already been developing to describe the behavior of water molecules in clouds around Saturn.

What's amazing is that the modelwas built without knowledge of the observation. Those of us in this small modeling community were using data from Cassini, Voyager and the Hubble telescope, along with established physics, stated Tim Cassidy, a recent post-doctoral researcher at JPL.

The results show that though most of the water in the torus is lost to space, some of the water molecules fall and freeze on Saturn's rings, while a small amount, about 3 to 5 percent, gets through the rings to Saturn's atmosphere. This is just enough to account for the water that has been observed there.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.