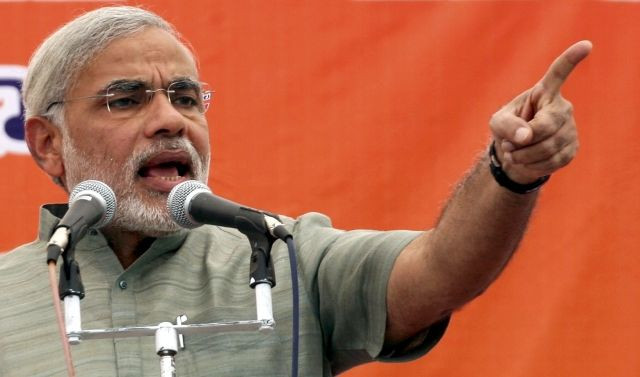

India 2014 Elections: BJP Leader Narendra Modi's Bromance With Japan's Shinzo Abe

If the prime minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, could vote in India’s upcoming elections, he would surely cast a ballot for Narendra Modi, the prime ministerial candidate for India’s right-wing opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Abe and Modi are not only fellow nationalist, hawkish conservatives, but also long-time friends with shared views on many issues and could help each other greatly in the years to come.

ForeignPolicy.com reported that when Abe was elected to a second term as Japan’s prime minister in a landslide in late 2012 (he previously held the top job from 2006-2007), one of the first foreign dignitaries to congratulate him was none other than Modi, the chief minister of the Indian state of Gujarat, not the leader of a sovereign nation.

Shrey Verma of ForeignPolicy.com noted that a phone conversation between the Japanese prime minister and the Gujarat chief minister was rather “odd by strict standards of protocol,” but underscored how the “personal relationship between the two men and the economic partnership between Japan and Gujarat has thrived over the years.”

Verma noted that in the wake of the deadly communal riots that swept through Gujarat in 2002 and killed about 1,200 people (a tragedy many blamed on Modi for not using his authority to prevent, or at least control), the U.S. and some western countries turned their backs on Modi, prompting his provincial legislature to “look east” for trade opportunities, especially Japan. Modi himself journeyed to Japan in 2007 (the first such official visit there by an Indian chief minister), an event that opened up new investment conduits between Gujarat and Tokyo. During that trip, Modi met with Abe, other cabinet ministers, as well as many of Japan’s most powerful industrial and banking executives.

Ever since, Verma said, Gujarat has attracted significant foreign investments from Japan for infrastructure projects, and new automobile plants, among other ventures. In 2012, almost 120 Japanese investors visited Gujarat to discuss future financial deals and investments in the province. For example, Japan's Suzuki Motor Corp. will invest $488 million for a car factory in Gujarat, which is expected to be operational by 2017. By 2015-2016, private Japanese investment in Gujarat is expected to reach $2 billion. (For the whole of India, Japan reportedly plans to spend billions of dollars on infrastructure projects.)

Thus, Japanese diplomatic and trade delegations have consistently treated Modi like a cabinet member or even head of state, not just the chief minister of a state, suggesting an ever-closer relationship between Modi and Japan’s power structure. Now, in the spring of 2014, with polls predicting that Modi’s BJP will defeat the incumbent Congress Party, thereby elevating Modi to the top position, the warm relationship between India and Japan is likely to strengthen even further, a bulwark against not only China’s looming dominance in Asia, but also the United States, which has “pivoted” much of its military presence towards the Asia-Pacific region.

But Abe also enjoyed friendly ties with the outgoing Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh, of Congress. The Economic Times reported that Abe admires Singh, considering him a “mentor.” Under Singh’s two terms and 10 years in office, India and Japan formed closer strategic ties, as their greatest mutual rival on the Asian continent, China, has grown in economic and military power. Indeed, aside from Russia, Japan is the only other country on earth that India holds annual summits with. New Delhi and Tokyo have also firmed up energy partnerships, defense programs, maritime security arrangements and economic investments.

Leaders from both countries have exchanged high-profile visits in recent years. In fact, even when Abe was the leader of the Japanese opposition in 2011, he visited New Delhi to confer with Singh. Even Japanese Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko made a historic visit to India late last year [their first trip there in fifty years], while Abe attended India’s Republic Day celebration in January 2014 in New Delhi as an honored guest. Now, with Modi waiting in the wings in New Delhi, Abe is very well positioned to embrace India even deeper.

As relations between China and Japan continue to sour – over territorial and maritime disputes, over North Korea, over China’s stridently militaristic stance, among many other issues -- an India led by Modi could serve to further rankle the leaders in Beijing. Consider that India invited Japan to participate in the U.S.-India Malabar Naval exercises scheduled for later this year. Already, in recent months, the Japanese and Indian Coast Guards conducted joint exercises off the coast of Kochi in southwestern India, while the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and the Indian Navy performed their second bilateral exercise off the coast of Chennai in southeastern India. ForeignPolicy.com also noted that India is considering buying military aircraft from Japan for $1.65 billion – which would make India the first country since World War II to make such a purchase from the North Asian power.

India and China also have their own territorial disputes along their 2,500-mile border, including imbroglios over Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh. But it is well worth remembering that Modi has not rejected China – indeed, he visited China in 2011 (at a time when the west, especially the U.S., was closed off to him) and he was received like a visiting head of state. Modi, for his part, also invited Chinese investments in Gujarat, as he had similarly extended such entreaties to Japan.

However, despite Modi's appeals for Chinese investments in India, he has expressed his strident opposition to China's expansionist policies in no uncertain terms. The Financial Times reported that Modi warned China to shelve its “expansionist attitude” during a recent speech in Arunachal Pradesh, a Himalayan state that neighboring China claims as its own (and which Beijing refers to as “South Tibet”). “No power on earth can take away even an inch from India,” he said a rally in the town of Pasighat while attired in native garb. “I swear by this land that I will not let this nation [India] be destroyed, I will not let this nation be divided, I will not let this nation bow down.”

Sanjaya Baru, director for geo-economics and strategy at International Institute for Strategic Studies and honorary senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, wrote in the Indian Express that if Modi is elected prime minister, he will, like his Japanese counterpart, follow a more nationalist foreign policy, partly to revive the “national mood in a dispirited country.”

“Modi seems to recognize the value of Abe’s combination of investing in domestic economic capability and external strategic capacity for nation-building,” Baru noted. “Modi’s domestic policy focus, drawing from Gujarat’s experience, has been on building India’s economic capability. His political rhetoric focuses on the need to revitalize a moribund economy, which is exactly how Abe came to power in a depressed and depressing Japan.” Now, both Abe and the next-would-be Indian leader Modi, might need a third Asian partner to counter China.

The prominent Indian political analyst Jaswant Singh has proposed that India, Japan as well as South Korea could form a three-pronged cooperative security front to challenge China. Writing in Gulf News, Singh, a former Indian finance minister, foreign minister and defense minister, noted that South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Japan's Abe were both alarmed by China's “unilateral declaration last November of a new Air Defense Identification Zone, which overlaps about 1,158 square miles of South Korea’s own ADIZ, in the Sea of Japan,” prompting a move to upgrade defense and security links (including joint cooperation deals on nuclear energy) with India on China's southern flank.

In January of this year, Japanese Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera conferred with Indian defense officials for four days to hammer out specifics of a bilateral security arrangement to “strengthen the strategic and global partnership between Japan and India,” including regular joint-combat exercises and military exchanges to cooperation in anti-piracy, maritime security and counter-terrorism.”

Michael Kugelman, senior program associate for South and Southeast Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, commented that the India-Japan relationship is arguably one of the most cordial partnerships in Asia. “The two countries have grown particularly close in the last few years, as both have become increasingly concerned with China's rising influence in Asia,” he said. “Concern about China, in fact, is probably the chief reason why Tokyo and Delhi are so close.”

But Modi must also focus on India's sluggish economy, and here again Japan could come to the rescue. Bilateral trade between Asia's two largest democracies is ripe for expansion. In 2011-2012 such volume amounted to only $18.4 billion, versus $65.5 billion in India-China trade (in 2013) and an astounding $329 billion in annual trade between erstwhile “enemies” China and Japan last year. Indeed, some 90,000 Japanese companies are now based in China, versus less than 2,000 in India, according to the Free Press Journal. Consequently, the potential for India-Japan trade is huge. Kugelman noted the “very strong economic dimension” to the blossoming India-Japan relationship. “And as a businessman, this is something that a Prime Minister Modi would want to build on,” he said.

However, in the event that Modi wins the election, he will likely face bigger challenges than his apparent ally in Tokyo who gained a dominant mandate in the 2012 elections in Japan. As Andy Mukherjee explained in Reuters, Abe's Liberal Democratic Party now controls both houses of parliament in Tokyo, while Modi's BJP (if it win the elections) are unlikely to gain a decisive majority in the Delhi parliament, which would lead to the formation of coalition partnerships that would dilute the potency of Modi's domestic and foreign policy measures. But, Mukherjee noted, Modi could find some help from Abe. “Japanese businesses, banks and pension funds want to invest, but Japanese society is too old to utilize many new investments,” he wrote. “The solution might be to invest more in India, which has a young population and desperately needs infrastructure.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.