The Inside Story Of How Pakistan Took Down The FBI’s Most-Wanted Cybercriminal

Just before dawn on Feb. 14, in a quiet residential suburb of Karachi, Pakistan’s chief cybersecurity officer, Mir Mazhar Jabbar, stood silently outside the home of Noor Aziz Uddin -- a man the FBI calls one of its “most wanted” cybercriminals. Jabbar knocked. Standing behind Jabbar was a team of local Karachi police officers, waiting to raid Uddin’s home and place him under arrest.

Uddin, inside, knew that investigators were after him. For the past 2 1/2 years, Uddin had been on the run, the subject of an international manhunt. According to the FBI, Uddin was the mastermind behind a global phone fraud. Most recently, he'd been seen in Saudi Arabia, but he also had been known to travel to the United Arab Emirates, Italy, Malaysia, Pakistan and even, of all places, Newark, New Jersey.

But really, he could have been anywhere.

Uddin was a slippery character -- a 52-year-old hacker who used multiple aliases, a guy with a massive bank account who seemed to always be one step ahead of the law. In 2012, he was arrested by Interpol but, because of an evidentiary snafu, he walked. The next year, the FBI put a $50,000 bounty on his head for any information that could lead to his arrest.

Then, in early 2015, that tip finally came in. It landed in Pakistan's Federal Investigation Agency, and was directed to Jabbar, the cybersecurity official. The tip was a cell phone number that apparently belonged to Uddin. Jabbar contacted the wireless service provider. The carrier then gave him access to the phone's GPS coordinates.

And that's how Jabbar ended up on Uddin's doorstep last month.

The irony that Uddin would ultimately be found because of a hacked phone number was not lost on Jabbar. According to the FBI, Uddin is the mastermind behind a massive phone hacking crime ring that netted him and an accomplice, Farhan Arshad, a massive fortune. Over about four years, from 2008 to 2012, they grossed more than $50 million by hacking phones -- mostly landlines -- all around the world.

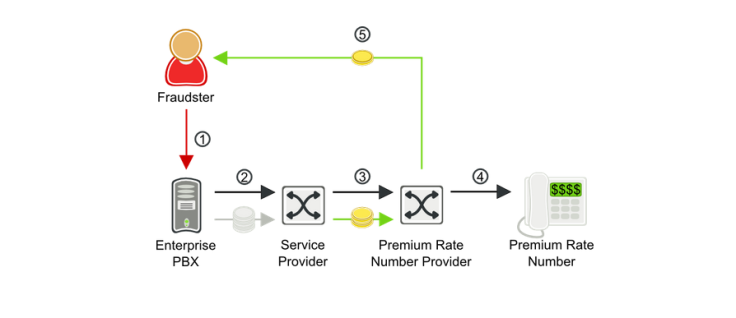

Most people are familiar with the idea of credit card hackers. But very few know about phone hackers, or PBX (private branch exchange) hackers, or even "phreakers," as they’re referred to by insiders. According to experts, the scam is on the rise -- and it's startlingly simple. The FBI says that Uddin, along with Arshad, would hack into the phone lines of U.S. companies, hijack their phone numbers, and begin auto-dialing like crazy. They’d use the numbers to call premium-rate lines, which, typically, charge the customer anywhere from 50 cents to $3 per minute.

But the crux of the scam is this: The hackers actually own those premium-rate lines, so they’re really just paying themselves by dialing with their victim's phones.

How It Works

It's a little bit complicated, so imagine it this way: Someone steals your iPhone. But instead of just selling it on Craigslist, they use it to dial one of those $3-per-minute phone sex lines, over and over, until you’ve racked up thousands of dollars in fees.

Now, imagine that same person who stole your iPhone actually owns that sex line that he was dialing, and you -- the unsuspecting user -- are forced to pay the bill to your carrier at the end of the month. Unfortunately, if you try to dispute the bill, your carrier will just shrug -- according to the terms of pretty much all user agreements, whoever actually owns the line is on the hook for the bill.

In Uddin’s case, the hacked entities were seemingly random businesses. The FBI’s official indictment doesn’t name specific entities, but it lists examples: One business in Livingston, New Jersey, was hacked for $24,120. Another, in Englewood, New Jersey, was charged $83,839.

The hacks themselves typically lasted for less than a day, usually on a weekend, when no one is in the office.

One might think this type of hacking is relatively fringe -- it’s not. Each year, PBX hackers pilfer some $5 billion from U.S. companies, an amount that places their scam in direct competition with stolen-credit-card scams. And despite the fact that it's so massive, and on the rise, few people seem to talk about it. “It’s like the ugly stepsister of credit card fraud,” says Shane MacDougall, a well-known cybercrime expert. "There’s even people in the security industry that don’t know about it.”

Why is it so unheard of? One reason is that the victims of these scams are often small-to-midsize businesses. Fearful of the negative publicity that surrounds the stigma of a hack, they often just pay the bill. Plus, it’s nearly impossible to get your local police involved. The dialers typically reside in the Middle East, Asia or Africa, and they almost always use virtual private networks (VPNs) or block their caller IDs to maintain their anonymity.

Uddin, who has a round face and a long black beard with a skunk-like white streak down its center, employed dozens of these dialers around the globe, the FBI says. These people lived in the Philippines, Switzerland, Spain, Singapore and Italy.

But Uddin was clearly the leader of the pack. As one source put it, Uddin was “the brains, the kingpin, the master -- the designer of the scheme.” Over four years, Uddin and his syndicate rang up 13 million minutes of fraudulent phone calls from 4,800 hacked entities. Ultimately, the crime spree came to an end.

On the morning of Feb. 14, Jabbar gave the command to raid Uddin’s home. Uddin apparently surrendered peacefully. Standing outside, Jabbar, the cybercrime chief, felt a surge of pride. “When you grab a criminal like [Uddin],” Jabbar said in a phone interview recently, “everybody is happy.”

Happy, though hardly satisfied. Arresting Uddin may have been one accomplishment for law enforcement, but Jabbar knows there are literally thousands of others out there, committing this crime every day.

Change Your Passwords

A PBX scam can begin as simply as giving the wrong person your business card. The most simple way hackers gain entry to your phone line is, surprisingly enough, through your voicemail. “That’s where your bad guys get creative,” says Paul Byrne, founder of PBX Wall, a fraud detection software company.

"PBX" is a term that’s ultimately used to describe any company’s phone system. Typically, hackers will call a landline and wait for the voicemail system to activate. Then, the hackers will begin guessing the voicemail password. They can do it manually, but more often than not, they use software with “brute force” capabilities, just like it’s done in computer hacks. Once they get your password, and manage to break into your system, they change your call forwarding service to the premium-rate line that they own.

After that, they’re in the money.

Hackers will use robo-calling software to dial your line hundreds, if not thousands, of times. But since they’ve set up call forwarding to their premium-rate line, the call silently forwards to their number every single time. In other words, you could be sitting at your desk and not even notice that your phone is forwarding your calls to a random overseas number, costing your company thousands in phone charges.

“If the bad guy breaks in on Friday and it’s identified on Monday, the average fraud can be $100,000,” Byrne says. “Typically what happens is the victim reports it to the carrier, at which point they deny accountability."

He adds, “We refer to this problem as the telecom industry’s dirty little secret.”

Mike Crown, a telecom expert, agrees. “What people don’t realize is that the carriers don’t lose,” he says. “If you get hacked, and somebody runs up a $100,000 phone bill, you’re obligated to pay that bill, even if it’s fraud. You can argue, but the courts say it’s your problem and not the carriers'.”

Phreaker History

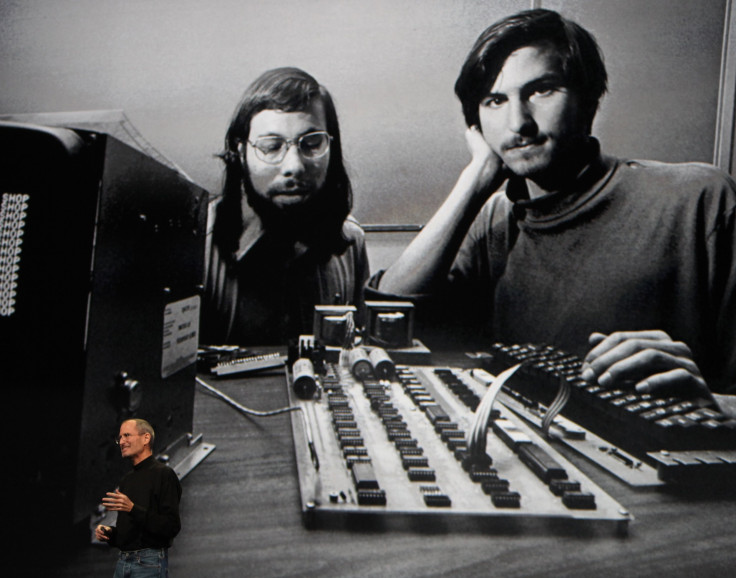

Interestingly, PBX hacking has been around since the late 1950s but has morphed over time. In the beginning, it was really nothing more than a dumb prank. Clever techies -- who called themselves “phreakers” -- would break into phone systems for the thrill of the hack. Even Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had fun with phreaking in the early 1970s.

Somewhere around 1973, Wozniak claims, he managed to route his call to the Vatican’s phone system. "In this heavy accent I announced that I was Henry Kissinger calling on behalf of President Nixon,” Wozniak told the Atlantic recently. “I said, 'Ve are at de summit meeting in Moscow, and we need to talk to de pope.’”

The Vatican apparently told him the pope was sleeping.

But when premium-rate numbers were introduced in the 1980s, hackers realized the potential value of exploiting those lines. One of the most lucrative premium lines ever was the Hulk Hogan Hotline, where you could call the famous pro wrestler and listen to a precious recording of his life advice -- for the tidy sum of $1.49 per minute.

In the past, phone hackers could hack premium-rate lines for profit, but the sums of money were relatively small. After all, older phone systems could accommodate only a few simultaneous calls at one time.

But now, most phone systems used by companies in the United States are operating on the Internet, specifically through VoIP (voice over Internet protocols). Those systems have way more bandwidth than old-school landlines, which means hackers can run hundreds -- potentially thousands -- of calls at once.

“Unfortunately, VoIP has fueled the boom in PBX hacking,” says Jim Dalton, a PBX expert and the founder of Transnexus, a software company in Atlanta that manages VoIP networks. “In the past, when you bought a telephone line, you typically bought a circuit with a limit to how many calls you can make at once.”

YouTube Phone Hackers

Plus, there’s another factor driving this boom: the ease and popularity of sharing information on YouTube. Hackers will routinely post “how to” videos on YouTube, offering “best practices” to fellow fraudsters on PBX hacking. “There’s everything from YouTube videos to hacking forums,” says MacDougall, the cybersecurity expert. “There are forums dedicated to nothing but PBX hackers. Never had hackers had so much access to information. As a hacker, it’s all handed to you.”

MacDougall says the worst phone-hack case he ever saw was at a brokerage house in 1999. According to MacDougall, the company -- which he cannot name because of a nondisclosure agreement -- was doling out about $30 million every quarter in fraudulent phone charges.

“It was kind of insane,” he says. Rather than call the police, the brokerage company ate the costs of the hack, thus averting a public relations nightmare.

MacDougall says that phone hacking is actually fairly preventable. All it really takes is better internal phone security measures, and daily checks of phone logs.

“The best fire departments are the ones with no problems -- it’s the same with this,” MacDougall says. “If companies put more emphasis on prevention,” he says, they can avoid thousands of dollars in damages.

Behind The Hacks

Ultimately, little is known about the men and women perpetrating these scams, but if anyone has any idea, it’s Roberta Aronoff.

Aronoff serves as executive director of the Communications Fraud Control Association, a telecom trade group based in New Jersey that monitors the number of phone hacking incidents each year. She routinely works with law enforcement agencies like the FBI on their investigations into phone hackers.

Every two years, the organization releases statistics on the industry. The latest figures available, from 2013, show that phone hacking has resulted in $4.42 billion in fraud. Aronoff says the 2014 statistics won’t be available until 2015, but she is almost certain phone hacking has continued to rise. “Unfortunately, the current thinking is that the answer is that it is increasing.”

It’s increasing, interestingly, not because of kingpins like Uddin, but mostly because of the low-level “grunts” or “dialers” who can operate this scheme with nothing more than a cell phone and an Internet connection. Uddin, however, was far from a grunt. With his hacked loot, Uddin reportedly went on a real estate spending spree. At the time of his arrest, authorities claim, Uddin had purchased nearly 50 plots of land around Karachi, and was even investing about $400,000 in various business ventures.

Uddin's Fate

Currently, Uddin is in jail in Pakistan, awaiting trial. It is unclear if the FBI plans to extradite him. An FBI spokesperson declined to comment for this story, saying only that the agency does not comment on ongoing investigations.

In a strange twist, Uddin’s main accomplice and co-defendant, Arshad, actually tried to get Uddin to stop the scheme about three years into the crime. According to the FBI indictment, which was filed in 2012 but recently unsealed under a federal court order, Arshad admitted “having second thoughts” in 2011.

According to the FBI's criminal complaint, Arshad sent Uddin an email Dec. 16, 2011, saying he wanted to “return all his luxuries ... rather than to continue making money through their venture.” Arshad even “further implored” Uddin to “consider turning to a life of honesty.”

It didn’t work.

As the FBI notes, despite the “confessional email,” the two men “continued to send fraudulent telephone traffic to fraudulent premium numbers and profit from such actions.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.