The Long Road Home

Louisiana's Road Home rebuilding program was supposed to help those who lost their houses to Hurricane Katrina. Ten years later, the journey home is far from over.

Vanessa Gueringer is usually too busy -- too engaged in “fightin’ mode,” she says, on behalf of her family and her neighborhood -- to spend much time admiring her house. But lately, as the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Karina has approached, she’s been taking a hard look at the place she calls home in the Holy Cross neighborhood of the Lower 9th Ward.

To outsiders, it’s a lovely place. The nearly 100-year-old “shotgun house,” as such long and narrow residences are called, is airy and welcoming, with light blue siding, white trim around the windows and a terra cotta rooster-comb finial -- a New Orleans tradition -- perched haughtily on the roof.

But when Gueringer, 60, looks at her house, she sees pain and struggles woven into the building. She recalls the water line that once ran along every interior wall nearly as high as her forehead, the final gift of the canal waters that coursed through the levee breaches and flooded the Lower 9th, ruining nearly all of Vanessa’s possessions and all but destroying her nearby childhood home, which is still owned by her 100-year-old mother.

“The big takeaway is the Road Home is still a very long road for those African-American families who lived here for generations and who could not return home."

Gueringer sees the point on her roof where, in one fateful moment after the storm, her husband Hank became incapable of shouldering the task of rebuilding. She remembers the endless paperwork and bureaucracy that came with asking for the money that was promised to make her home whole again, a system that offered so little to rebuild her mother’s house, it was a slap in the face.

And outside her home, she sees proof everywhere of those who’ve never been able to return home: the empty lots next door, the concrete front steps that lead nowhere around the block from her, the abandoned home just down the street that still sports a spray-painted white X left by a search-and-rescue team that went door to door looking for bodies in the weeks after the hurricane.

“My house came a long way, but it’s not what I want it to be,” said Gueringer, her large hoop earrings swinging as she gestures angrily. “Parts of my house I love, but other parts drive me crazy. I don’t know when it will ever be fully repaired.”

Gueringer's home is emblematic of Louisiana’s $10.7 billion Road Home rebuilding program, the largest housing aid effort in American history, designed to help Gueringer and thousands like her recover the homes they lost to Katrina. From the outside, the program, managed by the state’s Office of Community Development, appears a success: $9 billion given to more than 130,000 homeowners to reconstruct their homes or buy new ones, with the vast majority choosing to rebuild and following through on the plan.

“The Road Home program really did what it was supposed to do, and it did it well,” said Steven Anderson, public affairs director for ICF International, the private contractor chosen in 2006 to administer it. “ICF did something that had never been done before and administered the largest program of its kind in the history of the country, and with admittedly some bumps along the way, ICF fulfilled the intent of the program.”

As a result, said Pat Forbes, director of Louisiana’s Office of Community Development, which oversees Road Home, the rebuilding program proved a major factor in the revival of New Orleans, which emptied out after Katrina but has since regained 84 percent of its population. "I would say that while there were certainly things that could have been done better, it has had a very positive impact on the recovery of the state," he said.

But people who have endured frustrations like Gueringer’s say that depiction is but a narrow slice of the full story. As they tell it, Road Home has been so plagued with problems -- lengthy delays, maddening and insulting red tape, demands for homeowner documents that had been washed away or never existed, loopholes that fostered contractor fraud and policies seemingly designed to hurt those most in need -- that it has left its recipients beleaguered by bureaucratic battles and often lacking adequate recovery money to fix their homes.

A 2008 report by the research institute PolicyLink found at that point, Road Home had left 81 percent of recipients in New Orleans without enough to rebuild fully.

While supplementary grants aimed to address shortfalls, these programs failed to take into account that many people tapped their rebuilding money to cover living expenses while they waited to rebuild, once again leaving them without enough to finish the job. Louisiana Monday announced new administrative remedies designed to provide these homeowners with additional funding, but some say that 10 years out, the damage has already been done. These critics say Road Home is in part to blame for keeping 100,000 New Orleans residents, the vast majority African-American, from making it home at all.

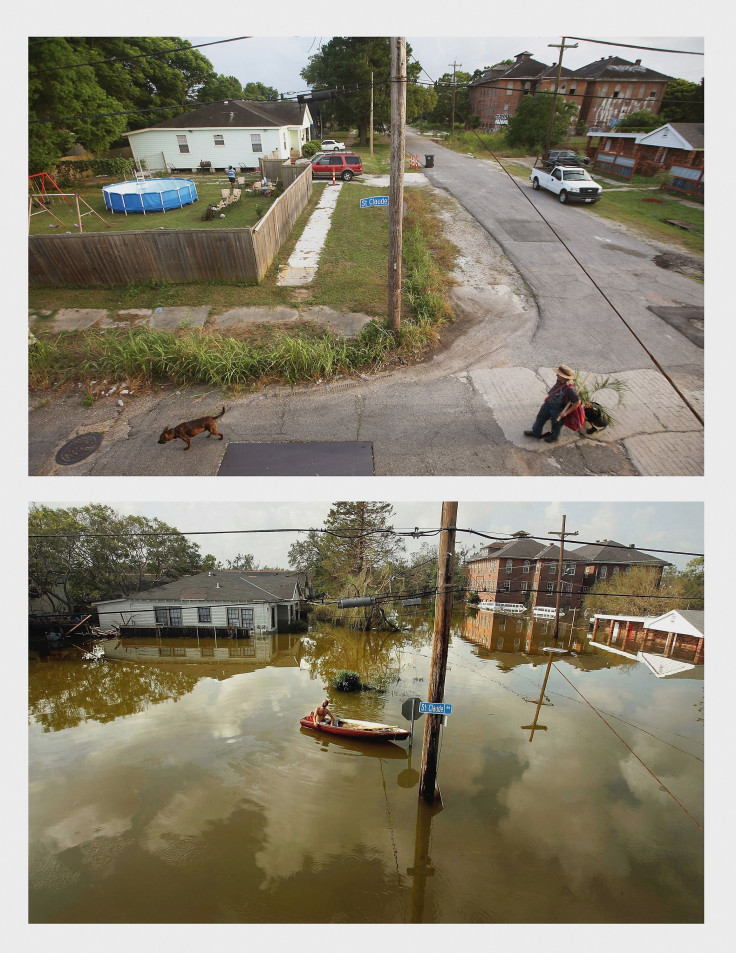

Gueringer’s community, the Lower 9th Ward, was the scene of Katrina’s greatest destruction. Images of devastation here helped inspire programs like Road Home. Yet the results of the program and the bitterness it has engendered have turned the Lower 9th into a prime illustration of how Road Home often fell short of the goal laid out in its name.

The section was once home to roughly 14,000 residents , nearly all African-American, but only 38 percent of the households in the most heavily damaged part of the Lower 9th have returned, by far the lowest rate in the city. Of the 2,844 homeowners who lived in the area before the storm, 814 sold their properties to the state, and the vast majority of those lots remain unoccupied. Roughly half of the area’s homeowners received rebuilding money from Road Home, agreeing to restore and reoccupy their houses within three years of obtaining the funds. Yet as of 2010, only 705 homeowners were living in the neighborhood, meaning two years after the vast majority of Road Home funds were delivered, at least half of the recipients in the area still weren’t home.

“There is a really crucial tie between the Road Home program and what the city looks like now,” said Cashauna Hill, executive director of the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center. “Did it provide some assistance to homeowners who were looking to rebuild and come back to New Orleans? It did. Did it make everyone whose home was destroyed whole? We know it did not. I do think it is an extremely important factor in why African-Americans haven’t returned to the city in the numbers that were living here pre-Katrina.”

The legacy of the country’s most ambitious disaster recovery effort isn’t as simple as the number of grants distributed or homes rebuilt. The program derailed political careers, buoyed the fortunes of a private contractor whose checkered record left residents and officials howling that they’d been fleeced, shifted the socioeconomic makeup of one of the country’s most beloved cities -- and turned hitherto unassuming New Orleans residents like Gueringer, for better or worse, into fighters.

“The big takeaway is the Road Home is still a very long road for those African-American families who lived here for generations and who could not return home,” said Gueringer, the heat in her voice rising. “We came back, and it’s been about punishment ever since. Everything you see rebuilt down here is from some hellified fighting.”

'Like Everything Was Dead'

Hunched in the backseat of a Suburban, Gueringer watched the spindly arms of the live oaks along St. Claude Avenue pass by her car window, the pounding in her chest growing as she approached her destination.

It was a sunny day in October 2005, and she was sneaking back into the Lower 9th Ward. Like many city residents, she’d evacuated on Aug. 28, the day before Katrina hit, heading out of town with her husband Hank, her daughter Ashley, 17, a few valuables and enough clothes to last four or five days. But she found herself holed up at her sister’s house in Baton Rouge for weeks on end, eyes glued to the TV for reports on her neighborhood that hardly ever came. While residents began to return to other parts of the city, the Lower 9th remained indefinitely closed off. Gueringer took to repeating, “I want to go home,” so often, relatives likened her to Dorothy from "The Wizard of Oz."

Two months after the storm, she was unofficially getting her wish. For the past year, she’d been working with the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, or Acorn, helping it push the city to fix water leaks in her neighborhood and advocate for other local improvements. She and other displaced New Orleans Acorn members had driven into the city to attend a city council meeting when they realized the white Suburban they were in looked just like those Federal Emergency Management Agency personnel were driving around restricted parts of the city, save for the fact nearly all those vehicles were filled with white people. So with Gueringer’s African-American face hidden from view in the backseat, they’d cruised by the guards stationed at the St. Claude Avenue Bridge, and then she headed home. She had no idea what she would find.

Her mother’s house, on Charbonnet Street, fared the worst. This was where Gueringer had grown up, raised along with her older brother and sister by a single mother who worked as a housekeeper and cook for a well-off family in the French Quarter and danced as a member of the Million Dollar Baby Dolls, one of the first women’s organizations to perform during Mardi Gras. This was where Gueringer would launch excursions all over the neighborhood’s dirt streets on her periwinkle blue bicycle, often ending up at the Industrial Canal, where she’d sit on the levee and watch big ships cruise past. This was where she was when Hurricane Betsy flooded the Lower 9th in 1965, on her porch, watching the dark waters crawl up her front steps, towards her 10-year-old feet -- an episode that would leave her with a lifelong fear of the open water. And this was where she, like many residents of the Lower 9th, developed a fierce pride in her neighborhood, born from the fact this one-time backswamp was for a long time one of the only neighborhoods where African-Americans were welcome to buy homes and build their lives.

When Gueringer reached her mother’s home that day in October 2005, that life had been washed away. A mountain of tangled wood, dirt, trees and trash had been pushed against the backside of the house and an errant jet ski sat in the parched and cracked dirt near the front porch. Inside, the water had reached to the eaves, and everything was smashed and in disarray. “It was like somebody had a bowl of soup and just stirred it up with a spoon,” she said.

Before the storm, Gueringer had the forethought to put her mother’s photos on top of a bookshelf, but it had overturned like everything else. None of the photos survived.

Gueringer’s mother’s house itself was so damaged it wasn’t clear the building could be salvaged. At least Gueringer’s house, further away from the levee breaches on Tupelo Street, appeared to be in one piece when she arrived in the Suburban.

Inside was a different story.

Gueringer had leased the house in 1986 with Hank, her second husband, while she was pregnant with their daughter Ashley. When they first moved in, the residence had seen better days, but her husband, whom Gueringer met while they were both working for the maintenance department of the local school district, was a skilled craftsman. He built a home for them out of the disrepair, just like he’d spend his nights carving strikingly lifelike wildfowl from blocks of wood in their backyard shed. After a few years, they bought the house from its owners for $36,000, and eventually her husband, 22 years her senior, set to work building an addition off the side.

Yes, poverty was high in the Lower 9th Ward, and crime was a growing problem. But the neighborhood wasn’t besieged by inner-city turmoil, as news reports made it seem. The two were among the 59 percent of Lower 9th residents who owned their homes, the highest homeownership rate in the city. Among these tightly packed houses was a sense of intimate community. “It was still pretty close-knit families,” Gueringer said. “Neighbors knew each other and looked out for each other’s property.”

The couple were just a few weeks of work away from completing the addition before Katrina hit. Now, thanks to the storm, they weren't even at square one. Her stainless steel appliances in the kitchen were ruined, her bedroom set had fallen apart, her shoes and clothes were a rotting mess. Black mold was spreading along the walls, and the blades of the ceiling fans drooped like the petals of a dying flower. A cockroach scurried along the wall, the only thing that seemed to be alive for miles in the brown, empty landscape.

“There were no sounds of insects or birds,” she remembered. “It was like everything was dead.”

The Lower 9th was so ravaged, it was among the main locales targeted in the now-infamous “green-dot map” unveiled by the city not long after the storm: The neighborhood was slated to be abandoned to the elements, with residents relocated somewhere less prone to flooding. Gueringer and most of her neighbors didn’t like the sound of that. “People in Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and all of the other places that have had natural disasters. Were they resettled somewhere else?” she asked. “Why do we have to resettle somewhere else?”

“People in Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and all of the other places that have had natural disasters. Were they resettled somewhere else? Why do we have to resettle somewhere else?”

This was her home, the place she had lived most of her life. This was why, once people were finally allowed back into the Lower 9th, Gueringer and her family spent months cleaning out debris from the neighborhood and fighting forced demolitions of houses that could be salvaged. It’s why she’d pass her nights in the home they rented in Baton Rouge hunched over the kitchen sink, scrubbing away at moldy jewelry until she developed shin splints from standing so long on the hard kitchen floor. And it’s why in May 2006, when FEMA finally provided them with a trailer to live in on their property on Tupelo Street, the couple immediately got to work.

“Sheetrock needed to be torn out, electrical issues needed to be addressed; it was a monumental task,” Gueringer said. “But Hank was up to the task of being able to oversee what had to be done.”

That was, until he climbed onto the roof for the first time to begin repairs. Maybe he was suffering from exposure to elevated formaldehyde levels for which FEMA trailers like theirs would become known, maybe it was the stress of everything that needed to be done. Whatever the reason, Hank Gueringer suffered a major stroke. He’d had strokes in the past, but this one was worse -- and it caused him to fall 14 feet off the roof and onto the concrete slab.

He survived, but never fully recovered. Thanks to a weakened right hand, he’d never again carve his wildfowl, never again be able to build a house for himself and his wife.

If Gueringer and her family were going to truly make it home, they needed help.

Documents Lost To The Flood

On a hot mid-August morning in 2008, Gueringer arrived with her mother in tow at the Crystal Palace, a reception hall in eastern New Orleans, ready for a fight.

The hall was hosting an outreach session for applicants to the then 2-year-old Road Home rebuilding program. While Road Home ran 10 Housing Assistance Centers in South Louisiana where people could make appointments to pursue their grant applications, outreach sessions like this had recently been announced to provide assistance on a first-come, first-served basis.

“My frame of mind was, ‘I am going to have to go in there and do battle,'” she said. “Back then, everything was a battle with Road Home. You just assumed nothing was going to go smoothly.”

Much had changed since Road Home was launched. Unveiled by then-Gov. Kathleen Blanco in February 2006 and bankrolled with federal funds, the program offered Louisiana homeowners as much as $150,000 to repair or sell homes damaged by Katrina and the flooding, with the grants structured to give people incentive to return and rebuild. Road Home, Blanco told a U.S. Senate committee at the time, would be “our ticket to rebuild, recover and resume our productive place in our nation's economy.”

But the effort immediately encountered stiff challenges. Blanco, a Democrat, spent months wrangling with the Republican-controlled Congress to sign off on additional funding to cover the $7.5 billion program. (Originally Louisiana was slated to receive only slightly more rebuilding funds than Mississippi, even though the latter state, a GOP stronghold, had suffered significantly less storm damage.) When sufficient funds finally came through in the summer of 2006, Louisiana chose ICF International, a private contractor from Virginia, to administer the program. The three-year, $756 million contract was significantly larger than any project the company ever had undertaken.

Rebuilding programs are difficult by their very nature: The stakes are enormous, the needed infrastructure is often crippled, and a sense can take hold among those in need that the gravity of their situation is not being properly appreciated. “The high drama of the acute event is over, so the TV cameras have left and it’s not on the front pages any more,” said Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “There is this unfortunate collision between the lack of media scrutiny and the complicated nature of the programs involved that have left many people suffering way longer than they should in many parts of the world.”

“There is this unfortunate collision between the lack of media scrutiny and the complicated nature of the programs involved that have left many people suffering way longer than they should in many parts of the world.”

The people running Road Home found themselves contending with this reality. “There were built-up expectations by the time we were on the ground that when ICF arrived, checks would simply be handed out,” said Anderson, ICF's spokesman. “In fact, residents had to apply for grants, which took time. When we got there originally, a lot of the areas where we had to work didn’t have basic infrastructure. We had to build our operations from scratch in many, many cases.”

When the company opened its assistance centers in August 2006, it had to rely on satellite dishes for Web access since local infrastructure for Internet services had yet to be rebuilt fully.

Gueringer and others hoping to rebuild their homes had been waiting for nearly a year before Road Home began accepting grant applications. As Vanessa and her mother arrived at the Crystal Palace, joining a line of worried people clutching documents that stretched out the door, it was clear this ordeal was far from over.

“People were anxious,” Gueringer said. “People were like, ‘I am not going to get the resources I am entitled to, and I am going to be sent to jump through hoops again.’ ”

As part of the application process, Road Home required applicants to file extensive paperwork and submit multiple proofs of identity. “People had to get mug shots and have their fingerprints taken,” said Vincanne Adams, professor of medical anthropology at the University of California, San Francisco, and author of "Markets of Sorrow, Labors of Faith: New Orleans in the Wake of Katrina." “They were treated like criminals. It’s as if they assumed these people were guilty because they were getting something they didn’t deserve.”

Road Home administrators became notorious for losing paperwork and neglecting to provide application instructions in writing. Many people seeking help lacked necessary documentation, such as property tax statements and utility bills; the flood had stripped them away.

African-Americans in neighborhoods like the Lower 9th faced additional hurdles. Given the legacy of discrimination, with some banks long refusing home mortgages to black people, many had purchased their homes directly from former owners while keeping local bureaucracy out of the transaction. People in this situation -- and the descendants of these homeowners who’d inherited their property -- were often rebuffed by Road Home administrators: They lacked adequate proof of ownership.

Those with mortgages faced a different challenge. Many applicants were forced to use Road Home funds to first cover back taxes or pay off mortgages on homes they hadn’t been able to live in for years. That included Gueringer’s friend, Gwendolyn Adams, and her husband, Henry. After their mortgage company took the bulk of their grant to pay off their mortgage, they received just $22,000 in Road Home funds to rebuild their house in the Lower 9th, which had been completely destroyed by the levee breach five blocks away. That money dwindled away, used to cover a rental house in the 8th Ward as the couple scrambled to figure out what to do.

Fortunately for them, Henry Adams was a New Orleans taxi driver, and one day found himself driving a member of the National Association of Home Builders. The association decided to rebuild the Adamses’ home, free of charge.

“My road home had nothing to do with Road Home,” Adams said. “We had to circumvent Road Home in order to get home.”

It all added up to a process that appeared to stretch on indefinitely, especially since originally, ICF didn’t have deadlines as to when it had to pay grants. While Anderson cited dozens of ICF performance audits that never found a single case of fraud or abuse, a 2008 Rand analysis commissioned by the state of the nearly 60,000 people who’d been awarded Road Home grants by the end of 2007 found the average application process lasted 250 days. For many, the process stretched more than a year. For a few, wait times exceeded 500 days.

In late 2006, frustrated Louisiana lawmakers attempted to rescind ICF’s Road Home contract, a move blocked by the governor. And while Anderson at ICF noted the company would go on to meet 85 percent of the performance goals that were then put in place, in 2009 the state fined the contractor more than $1 million for failing to meet operational targets set the year before.

Eventually, some came to believe ICF’s record reflected not ineptitude but a hunger for profit: The company was paid for the time it spent processing applications, not just the number of applications it completed. The longer the process dragged on, the greater ICF’s take.

“At first I thought state officials and ICF were incompetent, but then I realized after about a year it was part of the plan,” said Melanie Ehrlich, co-founder of the Citizens Road Home Action Team, an advocacy group that worked with Road Home applicants. “Bureaucratic hassles, insufficient transparency and the great complexity of the Road Home Program allowed ICF to make it seem that there was more workload than anticipated in the original contract.”

Positioned as the cornerstone of her post-Katrina administration, Road Home’s woes, along with the disaster response in general, would sink Blanco’s career -- but in late 2007, before she left office, she quietly increased ICF’s contract by $156 million, a 25 percent increase, after the company argued its workload was greater than originally expected.

Anderson said program delays weren’t driven by the company’s bottom line; they were due to the unparalleled scope of the undertaking. “The process was slowed as a result of 179 program changes by the state over the course of the 36-month contract,” he said. “Whenever you do that, you have to stop the process, you have to bring people in, retrain them, then ramp up the process again. That is going to have an impact on how quickly things are going to get done.”

“The Road Home program was well-intentioned. The flaw was that the formula on which the rebuilding grants were based failed to take into account the history of segregation and discrimination in this country.”

The Gueringers were among the lucky ones. She’d taken their homeowner paperwork with her when they evacuated New Orleans before the storm. She had the wherewithal and determination to navigate Road Home’s intricacies. She applied for a grant in 2006, and less than a year later received $150,000 -- the maximum amount.

Gueringer’s mother, Fabiola Miller, wasn’t so fortunate. Road Home administrators questioned whether she really had lived in her home. Back when she spent some time in an assisted living facility, she transferred the title to Gueringer and her sister so they could manage it. She moved back into her house before Katrina, but the utility bills that proved it were lost to the flood. The state had issued a deadline of Sept. 5, 2008, for all Road Home applicants to submit proof they were occupying their homes at the time of the storm -- which meant this outreach session probably was her last chance to prove she qualified for money to rebuild.

Instead of offering reconstruction funds, Road Home had sent her a letter offering to buy the property, which had for three years been sitting gutted and empty, with plywood over the doors and windows. In exchange for her house, which had suffered far more damage than Gueringer’s, Miller was slated to receive $8,100.

Inconsistent and counterintuitive funding calculations like this would become legion, comprising one of the most serious complaints levied against the Road Home program. Instead of simply basing awards on the cost of rebuilding, Road Home originally calculated grants based on the home’s prestorm value, if that ended up being cheaper. "It was definitely a budget-driven policy," said Forbes at Louisiana’s Office of Community Development. But for Miller and many other people, this meant grants often fell well short of covering the real cost of their damage.

Road Home’s funding calculations also meant people with lower home values received less recovery funding than those with similar damages but higher-value properties. This arrangement penalized not just low-income homeowners, but African-Americans in particular, since longstanding discriminatory housing practices had left their houses undervalued compared to similar residences in white neighborhoods. This was especially galling given that lower home values in predominantly African-American neighborhoods in part reflected how these areas were more vulnerable to precisely the sort of catastrophe that had unfolded: When Katrina hit, 80 percent of New Orleans’ African-American residents lived in areas at risk of flooding, compared to 54 percent of whites.

“The Road Home program was well-intentioned,” said Hill of the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center. “The flaw was that the formula on which the rebuilding grants were based failed to take into account the history of segregation and discrimination in this country.”

The fact that poor and black homeowners were less likely to have insurance or other resources to cover damages further exacerbated funding discrepancies. PolicyLink’s 2008 analysis of Louisiana’s housing recovery found the average financial gap between total rebuilding resources and the cost to rebuild for white Road Home applicants was $30,863 while for African-American applicants it was $39,082. Inequities were even greater depending on the neighborhood. In Lakeview, a predominantly white and relatively affluent part of New Orleans that was hard hit by flooding, the average rebuilding gap was $44,000. In the Lower 9th, that gap was $75,000.

In 2011, the federal agency in charge of the Road Home program settled a class-action lawsuit alleging the grant formula discriminated against African-American homeowners, agreeing to pay millions more to hundreds of applicants who were shortchanged. That followed a $3 billion funding increase and program changes in 2009 that allowed more Road Home funds to go to low- and moderate-income households.

But Gueringer wasn’t about to wait around for a federal lawsuit or administrative tweaks to remedy her mother’s rebuilding troubles. Sitting with hundreds of others in the Crystal Palace’s sweeping reception hall, where she'd come to speak with Road Home personnel stationed around the room, she was prepared.

When she was directed to a table of attorneys, she handed over telephone bills with her mother’s name and home address, obtained from a friend at the phone company. That settled the occupancy issue -- although it likely helped that Miller looked at the lawyers with tears in her eyes and said, “I just want to go home.”

The two were directed to another staffer at the event to determine Miller’s rebuilding award. Tapping on his keyboard, he came up with $49,000.

“No,” Gueringer said. “That just won’t work.”

He tapped some more. “Would $122,000 work?”

“Yes,” she replied. “That is acceptable.” Then the two headed for the door.

“I didn’t want him to press any more keys,” she said. “It might revert back.”

Fertilizer For Fraud

Miller’s grant amount stuck. With that money, flood insurance coverage and an additional grant Miller received to help elevate her home, Gueringer’s mother had enough to fix her house and raise it several feet off the ground. Similarly, the $150,000 Gueringer and her husband received from Road Home, plus $13,000 more obtained from a historic renovation fund, was enough to bring their residence back from the brink.

At least that’s what Gueringer thought until she discovered the general contractor she’d hired to complete the work had installed substandard flooring, causing her new kitchen tiles to buckle and crack. “If my husband had been well, there is no way we would have suffered contractor fraud,” she said. Instead, a low-income legal aid program told her she’d need to pay additional contractors $65,000 to fix the damage -- money she didn’t have. With the help of the legal aid service, she took the contractor to court, but he filed bankruptcy before he paid a dime.

The Gueringers were far from the only Road Home applicants to suffer contractor fraud. The program was originally designed to pay grants in installments as work was completed, with checks made out to both the homeowner and the designated contractor. That way, if the work was substandard, the homeowner could withhold payment. But in 2007, the federal government announced all future awards would be in lump-sum payments to homeowners. "I think the reason was [the original approach] was going to require environmental reviews at each house, and that was going to take too long to get people their grants," said Forbes at the Office of Community Development. But the new system provided no way to safeguard against unscrupulous construction or homeowner mismanagement, and two years later, a study conducted in part by Louisiana State University found 9,000 households in southern Louisiana that reported being home-repair fraud victims since Katrina. Of this number, only 1 percent reported getting their money back, and more than 40 percent hadn’t been able to finish rebuilding.

In 2013, Vanessa applied to a supplemental Road Home program designed to help applicants who’d suffered contractor fraud, but she said she never received a response. Instead, Road Home seemed more interested in taking money back from her. That August, on the eighth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, the Gueringers were among the 55,000 Road Home grant recipients who received a “final notice” letter from the state warning they were suspected of spending their rebuilding awards improperly.

Gueringer hadn’t used the $30,000 of her $150,000 award earmarked for elevation to raise her house. But that’s because, like so many others, she needed her entire grant to make her house livable. “I ended up using all of the money they gave me addressing structural issues, sheetrock, electrical, furniture -- everything had to be replaced,” she said. Even if she had managed to set aside the $30,000 for raising her home, it likely wouldn’t have been enough to get the job done. According to FEMA’s own estimates for elevation projects, she’d need at least $48,000 to raise her roughly 1,500 square-foot home. While in 2008 the state offered FEMA hazard-mitigation funds to help homeowners make up the difference, this supplemental elevation program was plagued by delays and fraud, and Gueringer never bothered applying for it.

Now Gueringer may be on the hook for more money: She recently received a letter stating that Road Home lacked proof she spent $7,500 of her rebuilding money on removable metal hurricane shutters she was supposed to buy, even though she'd purchased the shutters and submitted the receipt years ago. Like so many other bits of Road Home documentation over the years, it probably fell through the cracks.

Gueringer threw away the “final notice” letter after she read it. “I was like, ‘You’ve got the gall to ask for money,’ ” she said. “The number of people who took the money and ran is minuscule. Compare that to the thousands and thousands who said, ‘I just want to go home. I just want to go home.’ ”

A New Sort Of Flood

The Lower 9th Ward is no longer the bustling neighborhood in which Gueringer grew up. Nor is it the post-Katrina scene of devastation, with houses in the middle of roads and a 200-foot barge marooned on top of a yellow school bus. These days, the Lower 9th is a different sort of place, one far more eerie, far more haunting.

Some lots sprout new or rebuilt shotguns, but others hold only the husks of abandoned houses, their roofs collapsed, with plywood blacking out the windows and vines spreading up the walls. Many more lots are barren save for tangled weeds and grass, the homes that used to sit there demolished and hauled away. The quiet emptiness increases closer to the levee breach, where many blocks now contain just a single occupied residence among the dereliction. It’s as if a new sort of flood is slowly spreading across the neighborhood, returning it to barren wilderness.

Navigating the fissured and broken streets in her dark blue Jeep,Gueringer interprets the desolation. The wooden pilings sprouting from a grassy lot, elevating a house that isn’t there? Contractor fraud. The half-built house swathed in Tyvek fabric that’s yellow from years in the sun? More fraud. The piles of rubble strewn across sidewalks? Cleanup jobs for the city that haven’t been requested since there are no residents around to make the call. The rusting metal sign that stands alone in an empty corner lot? The last remnant of a neighborhood funeral home that used to read, “We’ll be coming back.” It never did.

Renters in the Lower 9th didn’t come back, either. Rental units in the neighborhood dropped from 1,976 to 356 from 2000 to 2010. Considering that Road Home’s Small Rental Property Program, launched in 2007, has been even more beset by setbacks and failures than the homeowner program, it’s unlikely many of these units ever will come back.

Gueringer’s tour of the Lower 9th illustrates something else Road Home and other reconstruction efforts failed to take into account: Rebuilding homes isn’t just about constructing houses, it’s also helping to bring back the elements that turn those houses into a community. “You cannot just rebuild houses without rebuilding schools, hospitals, social service facilities and places to shop and have commerce,” said Redlener at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness. “That is a much larger task that is not appreciated by Congress when they are funding these rebuilding programs.”

“You cannot just rebuild houses without rebuilding schools, hospitals, social service facilities and places to shop and have commerce. That is a much larger task that is not appreciated by Congress when they are funding these rebuilding programs.”

A few sprouts of a community are starting to take root in the Lower 9th, like a fire station, a community center and a grocery store. But all of these have opened in just the past year, nearly a decade after the storm. When Gueringer drives past these scattered services, she doesn’t see victories, she sees the battles she and others waged to get them. That’s the sort of person she’s become since Katrina. Once terrified of speaking on camera, now it’s impossible for her to keep quiet.

Having quit her administrative job at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center after the storm and her husband’s accident, Gueringer turned to activism as chairwoman of Acorn’s Lower 9th Ward chapter. When Acorn imploded amid scandal and political attacks in 2009, she became vice president of A Community Voice, an organization founded by former local Acorn board members. She fought politicians over how they’ve transformed the city’s schools into an all-charter system. She fought city officials over all the houses in the Lower 9th they’d let succumb to blight. She fought tourism companies for offering “disaster tours” of her neighborhood. And she fought, ferociously, against the injustices she saw in Road Home.

Those efforts came at a price. “It affected my family, because a lot of times I was out fighting the fight,” she said. “My husband used to get mad at me for traveling everywhere.” That is, until he stopped talking, the damage from his stroke steadily getting worse. He progressed from a walker to a wheelchair and now spends much of his time silently lying in bed, his emaciated body plagued by renal cancer. Gueringer cares for him as best she can, but it’s not easy. “Some days, you can see in his eyes and his mannerisms that he’s disgusted,” she said. “He is in this shape, and it’s sad.”

Gueringer also looks after her mother, whom she convinced to move in with her last year after she discovered the gas running on the stove in Miller’s rebuilt house. It’s not easy balancing all of these tasks, all of these battles, but knowing what she knows, Gueringer said she doesn’t have a choice.

“Before Katrina, I was like most black folks in the city,” she said. “The politics in the city didn’t bother us. My life was good. But the storm opened my eyes to everything I didn’t know what was going on here. I transformed into this person that had to fight for my community. I had to fight for everybody.”

'The Journey Home Is Still Not Over'

Gueringer has a long to-do list of work she wants to get done on her home on Tupelo Street. She plans to plant mandevilla vines that will thread through her chain-link fence out front and welcome visitors with their bright pink flowers. She wants to cut back the live oak that spreads over her house, giving squirrels and other vermin easy access to her roof. Then there’s the substandard flooring that still needs to be replaced, and the fact that the house’s sinking foundation is leading to cracks in her walls. Before all that, she might get a new cabinet for two of her husband's wildfowl carvings: a pair of quails perched on a water pump, and a snow goose in flight. They were the first things she salvaged from the house after Katrina.

Similarly, there’s work left to be done on Road Home. Louisiana's Office of Community Development Monday announced changes to the 9-year-old program that will allow the state to use the $30 million remaining in unobligated Road Home monies, plus additional funding programs, to help the roughly 6,000 homeowners who received rebuilding grants but still haven't been able to fix their homes. The state also plans to reimburse as much as two years of housing costs for those who spent Road Home grants on living expenses while waiting to rebuild.

“[These] are things we know from conversations with housing advocacy groups and others close to homeowners that are big pieces of what’s keeping people from being able to return home,” said Forbes of the changes. But the state also announced aggressive plans to recover grant money from those who aren't compliant with their Road Home obligations -- which means unless Gueringer proves to Road Home that she used her elevation money for necessary rebuilding needs, she could be looking at a $30,000 bill.

ICF won’t be responsible for implementing these policy changes. Anderson said his firm processed 185,000 Road Home applications and approved 124,000 grants from 2006 to 2009, exceeding the original program requirements. Still, when the company’s three-year contract expired in 2009, David Hammer, an investigative journalist who’d exposed many of Road Home's shortcomings, reported at the time ICF was “generally reviled by Louisianans and essentially banned from new business with the state.” Louisiana awarded the remaining work to a different firm.

“To say the Road Home is a success is an outright lie.”

But that didn’t sink ICF’s fortunes; handling a program of Road Home’s magnitude proved transformational for the firm. “It is the case that Road Home propelled ICF as a company,” Anderson said. In September 2006, three months after winning the Road Home contract, ICF announced its first public offering in 37 years of operation. As reported by Davida Finger, formerly staff attorney at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law’s Katrina clinic, from 2005 to 2007, the company’s revenue quadrupled, and profits increased nearly threefold. The firm now holds lucrative contracts with the likes of the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Army and Head Start.

ICF also now is associated with another beleaguered disaster recovery effort. The state of New Jersey has contracted with the company to help staff recovery centers and handle other responsibilities related to damage caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. ICF assumed an expanded role in Sandy rebuilding efforts last year after slow grant distributions and other complaints led to the firing of the former contractor, Hammerman & Gainer Inc., the Louisiana company that replaced ICF as the Road Home administrator in 2009 and still manages the program.

For Redlener at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness, the fact that history seems to be repeating itself in Sandy rebuilding efforts suggests the country hasn’t learned from Road Home’s mistakes.

“When we experience a disaster, it inevitably leads to lessons learned,” he says. “Like, don’t give out grants in lump-sum payments, give them out in steps. And have more government enforcement of potential fraud. And have case managers that will help every single grantee navigate these very complex waters. But in our current economic and political environment, the final step of applying these lessons is paralyzed.”

In the Lower 9th Ward, people have learned a lesson from Hurricane Katrina and the Road Home program, one they’re applying every day: They can’t wait for others to rebuild their community. They have to do it themselves. “The real fear of the 10th anniversary is the world is going to be focused on us on Aug. 29, and on Aug. 30, they will never look at us again,” said M.A. Sheehan, director of the Lower 9th Ward Homeownership Association’s House the 9 Program. She’s working to raise money to help locate and advocate for the hundreds of Road Home families who still haven’t returned to the Lower 9th Ward.

“One of the best outcomes of Katrina is that a fundamentally vigilant population has evolved,” said Roberta Gratz, an urban critic and author of "We're Still Here Ya Bastards: How the People of New Orleans Rebuilt Their City." “They are much more activist-inclined, more willing to stand up to government resistance and play the part of a good citizen.”

Gueringer is among those who have been transformed. “To say the Road Home is a success is an outright lie,” she said. “People have been fighting on this long journey for 10 years. People had died, people have grieved to death. The journey home is still not over for those who remain in the diaspora.”

She’s having her next-door-neighbor, James, a jack of all trades, repaint her exterior. On a recent sunny afternoon, she steps outside in the boiling heat to check on his progress.

“Oh yeah, it’s gonna look good,” she said, gazing at her home. “It’s gonna look good.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.