Tempting Fate

As New Orleans residents celebrate the rejuvenation of their city, experts warn of a reckless delusion that has swept over the Big Easy in the decade since Hurricane Katrina's floodwaters subsided.

Considering the apocalyptic scene that unfolded in New Orleans a decade ago, as Hurricane Katrina breached the levees and wrecked much of a major American city, the affluent neighborhood of Lakeview amounts to a showcase of a remarkable revival.

Kenneth Taylor remembers how the stormwater tore open the nearby 17th Street Canal, unleashing walls of water as barriers crumbled across the city. Eighty percent of New Orleans was suddenly underwater, including all of Lakeview, which sits near the shores of Lake Pontchartrain. Taylor’s home stewed in 8 feet of water for two weeks while he and his family took refuge at his brother’s home in Lafayette. His insurance office on Harrison Avenue flooded to the roof, destroying all his files and furniture.

Not long after the storm, Taylor steered a borrowed boat down his block, ducking his head at intersections to avoid hitting traffic lights. He managed to grab clothes and family mementos from the second floor of his house, but everything downstairs was destroyed, consumed by mold and fetid water. Taylor later learned that some of his insurance clients died in the storm, including a man who suffocated in his attic.

“There’s a general self-congratulatory atmosphere and complacency in the city, which I find very disturbing. People don’t want to hear they’re still at risk.”

On a recent afternoon in Lakeview, though, shoppers stroll the wide brick sidewalks of a rebuilt Harrison Avenue, popping in and out of chic boutiques and cafes. Taylor’s once-swamped office building is now home to a high-end clothing store. Along surrounding residential streets, 3,000-square-foot, half-a-million-dollar homes sit on neatly manicured lots, having replaced the older, modest abodes that were here before Katrina. The few empty lots that remain are filled with bright yellow Caterpillar backhoes, fresh piles of bricks and wood house frames -- testament to an ongoing building boom. Property values have tripled in the area in recent years, as young, well-to-do families flock to the suburban-like streets.

“This area has just really gone gangbusters,” says Taylor, 58, a father of four, who has lived in the city all his life. “It’s really exciting times to be in most of New Orleans.”

Yet as residents and officials celebrate the development as the rejuvenation of an embattled city, climate scientists and coastal experts warn of a reckless delusion that has swept over New Orleans in the decade since the floodwaters subsided. Katrina delivered a lethal warning that climate change has rendered the Gulf Coast vulnerable to rising seas and ferocious storms. Even so, people here are doing what residents of any coastal community tend to do after a disaster: They are rebuilding, below sea level and up to the water’s edge, in the same ways and on the same terrain that succumbed to flooding the last time.

At the same time, ambitious plans to fortify the city from the growing threats of climate change -- shoring up natural buffers in the Gulf that protect land from storms, and redirecting stormwater -- have yet to fully materialize. The talk may be bold, but the money and political will are scarce.

“There’s a general self-congratulatory atmosphere and complacency in the city, which I find very disturbing,” says John Barry, who served as a member of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East from 2007 to 2013. “People don’t want to hear they’re still at risk.”

Indeed, residents in Lakeview and across New Orleans tend to cast such talk as overly gloomy. How could another Katrina-like catastrophe sweep in and wipe away their progress? For such bad fortune to strike twice in a lifetime seems unfathomable. Others have taken a measure of reassurance that the breaching of the 17th Street Canal was later blamed largely on faulty design and human error. Next time, federal officials have promised, a new $14.5 billion flood-protection system encircling the city will be there to keep water and land divided.

Taylor and his family are banking on that pledge. They moved back into their house in March 2009, after passing over four years in a modest rented house in the Uptown neighborhood, which suffered relatively minor flooding. Once back in their Lakeview home, the family ripped out counters and cabinets smothered in red and pink mold and stripped the walls and floors down to the studs. They didn’t elevate the foundation, which was already raised 2 ½ feet above the floodplain.

Today, picture frames line the walls. Taylor’s children -- in their teens and 20s -- shuffle throughout the house, their golden retriever trailing behind. No signs remain of the devastation that ripped through here 10 years ago.

“People wanted to get back,” Taylor says. “We just love it there.”

The Right To Rebuild

Far from alone in that sentiment, the Taylors are part of a wave that is delivering growing volumes of people and investment dollars to Louisiana’s coastal zone, filling in the very terrain that climate scientists say is most at risk of being inundated again when the next surge inevitably washes across the land.

Though New Orleans’ population still hasn’t fully recovered to pre-Katrina levels -- nearly 385,000 live here now, or about 80 percent of the city's 2000 size -- the city is seeing consistent growth. The population swelled by 12 percent between 2010 and 2014, according to the Census.

The city’s housing stock is similarly being replenished, although vacant lots and blighted properties remain in lower-income neighborhoods, where residents had fewer means to stage a real estate boom like the one in Lakeview. Katrina flooded or damaged about 184,000 homes and apartments in New Orleans, or nearly 80 percent of its housing stock, and almost all of its affordable and public housing. A decade later, roughly 81 percent of Katrina-damaged houses have been rebuilt or are being renovated, the University of New Orleans found in March in a curbside survey.

People have been able to establish homes here, on land no less susceptible to flooding than before Katrina, because of a defining feature of local life -- a near-absolute right for property owners to rebuild in the wake of disaster.

Land use regulations are generally permissive along the Gulf Coast. In New Orleans, initial conversation about barring development on vulnerable land in Katrina’s aftermath was quickly muted as an affront to communities that would have been abandoned -- not least, the poor, African-American neighborhoods that had suffered an outsized share of Katrina’s wrath.

“People can still build anywhere in the city that they want to,” says Robert Collins, a professor of urban studies at Dillard University in New Orleans.

Many residents find it impossible to consider abandoning their homes -- some for financial or emotional reasons, or a combination of the two. Families tend to stick together for generations here, perceiving potential moves to higher ground as the forsaking of community and heritage. Some stay because their lives are tied to the coast, whether they earn a living in tourism, on fishing boats or in the prominent offshore oil and gas industry. Add to this an incoming tide of “transplants,” or newcomers, who moved to New Orleans after Katrina, drawn by its culture and the chance to help the city rebuild.

For many people, day-to-day problems of life are more pressing than hypothetical environmental concerns, even after the trauma of Katrina. “You can’t worry about it,” says Stanley Gauchets, whose gas and service station in Lakeview took in 9 feet of water during Katrina. “If it happens, it happens.”

Not that he has forgotten how events played out the last time water claimed the land.

“We lost everything. It looked like a scene from a movie in a graveyard.”

“We lost everything,” Gauchets recalls. “It looked like a scene from a movie in a graveyard.” Coolers toppled over, fuel tanks emptied, a pickup truck turned on its side and an ice machine simply vanished. Next door, at a small grocery store, rats and flies descended on rancid piles of fruits and vegetables.

He remembers how an eerie silence washed over Lakeview in the months after Katrina. Birds stopped chirping. Leaves stopped rustling. Everything was tinted with ashen gray.

Yet as recovery continues, environmental dangers are mounting in coastal Louisiana, threatening to wipe out years of hard-fought progress. Because of climate change, hurricanes stronger than Katrina are expected to intensify and strike more frequently in the Atlantic region. Rising sea levels are increasing the flood damage caused by storms and heavy rains. At the same time, Louisiana’s wetlands are rapidly vanishing, eliminating the natural storm barriers protecting New Orleans.

Not least, the city is sinking, a fact that can be seen clearly in Lakeview. Three-foot-wide sinkholes and scattered potholes give drivers the sensation of riding on dirt mountain roads, not on asphalt streets in tree-lined suburbia. Land is caving because of the giant underground drainage canals that pump stormwater into Lake Pontchartrain, which weaken and dry out the city’s soil foundation and boost flood risk. During a typical heavy summer downpour, streets flood so much in some parts of the city that residents can kayak down the block.

Within the next 15 years, the coalescing climate threats could sink or damage an additional $275 million a year in coastal Louisiana’s existing property and infrastructure, according to the Risky Business project, which studies the economic risks of climate change. Across the Gulf Coast and Eastern Seaboard, higher sea levels, stronger storm surges and more intense hurricanes could rack up an additional $7.3 billion in damages by 2030, bringing the total annual price tag for hurricanes and other coastal storms to $35 billion, researchers estimated.

If the trauma of a natural disaster is felt acutely by the communities struck by storms, the costs of cleaning up and restoring shattered cities is ultimately borne by all American taxpayers. In 2012, the year Hurricane Sandy smashed the East Coast and tornados, droughts and wildfires swarmed the central U.S., the federal government spent nearly $100 billion in response to extreme weather -- more than the federal budget for education or transportation, and three times what private insurers paid out, a Natural Resources Defense Council report found. The 2005 hurricane season, including Katrina and Rita, cost the federal government nearly $56 billion.

Natural disasters will inevitably strike in any region, but costs will only continue to soar if the nation insists on building squarely in harm’s way and with the bare minimum of protection.

“In any coastal community, you can ask the question: Is the rest of the nation prepared to deal with the expense of restoring an at-risk community?” says Joshua Kent, a coastal geographer at Louisiana State University’s Center for GeoInformatics in Baton Rouge. “We have to decide if this is what we want, and I think that’s what we’ve decided already.”

The Geography Of Racial Inequality

In the years after Hurricane Katrina shattered the levees and wiped out entire neighborhoods, New Orleans and Louisiana leaders have forged plans to build the city back stronger and more resilient. Wetlands have been slated to be replenished, homes elevated and flood barriers fortified. The city’s stormwater and drainage systems were to be reinvented to accommodate expanded flows of water, rather than flushing it out and causing further damage.

Trickles of progress have been made on all fronts, but the kind of radical reinvention New Orleans needs to survive has yet to take root.

“Can I guarantee that New Orleans has a future 1,000 years from now? I don’t know,” says Mark Davis, who directs the Institute on Water Resources Law & Policy at Tulane University. “Five hundred years? I can’t tell you. But there is some limited capacity for this area to keep its head above water. Whether we’re smart enough to do it, and whether we’re given the luxury of time, we don’t know.”

The most straightforward way to mitigate risk of another Katrina-like tragedy might be to relocate low-lying communities to higher ground while limiting rebuilding in the danger zone. But such an approach would have required new laws. Before and immediately after Katrina, New Orleans lacked a comprehensive land-use plan and stringent zoning rules that might have guided development in such a strategic pattern. Residents and business owners were left to rebuild in the same ways they always had.

The federal Road Home program, which awarded $9 billion to help Louisiana homeowners move back, had no strings attached concerning location. And while federal flood insurance regulations adopted post-Katrina do require residents to elevate new homes above the floodplain, the rules have not restricted development in high-risk areas.

City and state officials have over the past decade moved slowly to correct the urban planning chaos that has characterized local development. New Orleans’ Master Plan, adopted in 2010, lists sustainability and flood resilience as among its guiding principles. In May, officials enacted a Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance to give that vision legal teeth. And still, the ordinance included no rules or initiatives to promote denser development on higher ground.

“The elected leadership, they’ve basically taken that off the table,” says Collins, the Dillard University professor. “They don’t want to consider shrinking the footprint of the city, mainly because it’s politically toxic. They know they’re going to be voted out of office if they do that.”

Early attempts to rework the city’s housing patterns after Katrina proved particularly controversial. Ray Nagin, the mayor at the time, launched the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, a team of urban planners and experts that unveiled a $17 billion vision for the city. On a map, green dots indicated which areas could become parkland, and in which sections residents would be allowed to rebuild as usual.

Proponents of the plan insist it was a mere conversation starter, a way to get New Orleanians thinking about how to limit their vulnerability before plowing billions of dollars into new houses, rental units and office buildings. But the “green dot” proposal -- like Katrina’s floodwaters themselves -- reinvigorated deep-seated tensions over the racial inequality that has defined New Orleans’ development throughout its history.

The highest land, near the Mississippi River, was home to largely wealthier, white residents. The lowest land -- the least valuable real estate -- was home to mainly African-American and lower-income residents, who hadn’t even had time to return home before they saw their neighborhood slated to be relinquished to the elements as future green space. Denying these communities the right to rebuild would have presented a politically untenable double whammy: These neighborhoods had been leveled disproportionately, in part because they had lacked the flood protections enjoyed by more affluent areas. Against that backdrop, the imperatives of planners and academics to limit development in harm’s way looked like a new form of redlining -- effectively shutting out poor, black households.

“It’s a really tricky thing,” says Imani Brown, a New Orleans resident and artist who is leading a community development project called Blights Out in the Mid-City neighborhood. “We do have to move in some way. But it would be nice if, as a result, the same people who are constantly disenfranchised are not the ones who are further harmed by the solutions.”

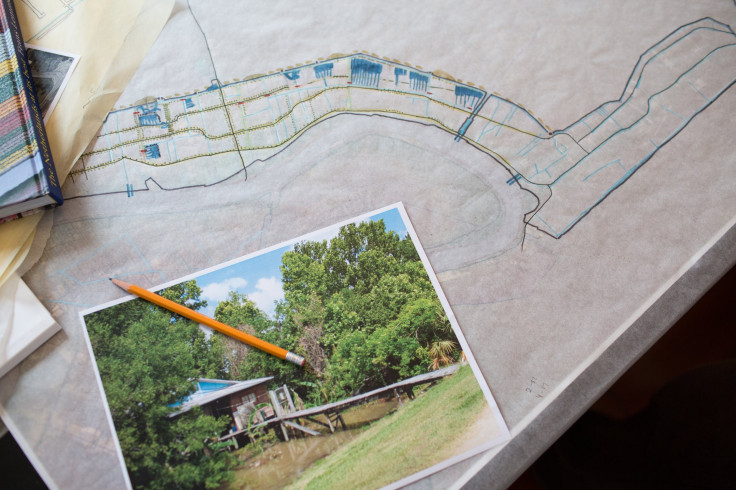

These days, low-lying, lower-income neighborhoods such as Mid-City, the Lower Ninth Ward and New Orleans East present a stark contrast to the vibrant scene in wealthier Lakeview, which itself sits several feet below sea level, but where residents had the means to swiftly rebuild. These communities are still lined with abandoned homes and vacant lots, where tall grasses and stranded concrete steps prompt stern warning and steep fines from city regulators. Many homes fell in disrepair after their owners couldn’t afford to return, or chose not to.

“You have to wonder,” Brown says, seated outside a coffee shop where local activists gather for meetings. “What is the state’s solution to climate change, and who are they going to sacrifice to save another?”

The green dot plan died swiftly in the months after Katrina amid widespread public backlash, and after Nagin -- now in federal prison on corruption charges -- distanced himself from the rebuilding strategy.

Collins and other urban planners say officials eventually will have to find a way to reshape New Orleans’ housing footprint to make living in the city safer for all residents. Collins says he’d like to see “inclusionary” zoning regulations that provide affordable housing in the highest elevated areas while allowing community groups to participate in land-use discussions -- two elements missing from the initial rebuilding plans.

“That’s the only way it would work politically,” he says.

Doing It Like The Dutch

Beyond the failed effort to move people away from flood-prone areas, urban planners and environmentalists have sought to limit the dangers that water poses to communities through tweaks to engineering and architecture. They have pushed to transform the city and its surrounding neighborhoods into Louisiana’s version of the Netherlands, with streets, parks and canals that capture and absorb stormwater, rather than pumping it through drainage canals or allowing it to swamp entire blocks.

Waggonner & Ball Architects and Greater New Orleans Inc., an economic development agency, have for the last five years touted an Urban Water Plan, which proposes multiple “living with water” projects inspired by centuries-old Dutch flood systems.

Ramiro Diaz, an architectural planner at Waggonner & Ball, is helping bring the plan to fruition. On an afternoon in early August, with the heat index topping 120 degrees, he drives through the city in his Prius, pointing out promising developments. At Parkway Bakery & Tavern, a popular restaurant known for its po’boy sandwiches, the parking lot is paved not with impermeable concrete but endless stretches of black plastic rings filled with gravel. The porous pavement traps rainwater and replenishes the soil, rather than letting it clog a maxed-out sewage system.

In Fillmore, a mostly middle-class neighborhood near New Orleans’ sprawling City Park, Diaz stops in front of a 25-acre expanse of green. For decades, the Sisters of St. Joseph’s convent occupied the lot. Katrina ended that. The Catholic order razed the building and made the land a public space, which Diaz’s firm wants to equip with lily ponds, cypress groves and tall grass patches. Plants capture water, pull it down into the soil, and the excess overflows into a freshwater swimming pool and wetlands habitat. The city is working to secure a hazard mitigation grant from FEMA to build the $19 million Mirabeau Water Garden.

Diaz’s own home boasts a miniature version of this stormwater system. In the courtyard of his apartment complex on Magazine Street, a metal container the size of a refrigerator collects rainwater that runs off the gutters. The water flows down into a smaller container, then another, and then into a lily pond, sparing his backyard from a deluge during summer storm season.

Along the way, Diaz also calls out the “missed opportunities” -- projects where developers and officials might have incorporated sustainable designs, but instead chose a more traditional approach.

A new Costco building has a sprawling flat rooftop and wide impermeable parking lot, which will send surges of stormwater directly into streets and overtaxed canals, instead of storing it in the ground. New Orleans is working to widen and deepen the canals, but the $1 billion endeavor will also worsen the city’s sinking trend.

Along Napoleon Avenue, construction workers plow huge metal pilings straight into the ground, diverting traffic down torn-up streets. Critics of the Southeast Louisiana Drainage Project say the money would be better spent on projects that fix New Orleans’ problems with sinking, not exacerbate them.

“We need to be more intentional about how we use our space if we’re going to be here another 50 years,” Diaz says, driving along the construction zone.

Diaz is especially frustrated with the Lafitte Greenway, a $9.1 million project that turned an abandoned railroad track between the French Quarter and Midtown into a 2.6-mile bike lane and pedestrian park, with gently sloping “bioswales” that retain floodwater. The Urban Water Plan calls for transforming a former shipping canal, which abuts the bike path, into a flood protection powerhouse that captures vast volumes of rain and storm surge and circulates it through existing drainage canals. The more ambitious leg of the project has stalled.

“The shift in New Orleans thinking of itself as a water city is more in the mind than the eye right now,” says David Waggonner, president of the architecture firm. “There’s a lot of conversation, and not enough work.”

Rebuilding Wetlands

Dozens of miles south of New Orleans, in the coastal zone, a similar lack of momentum is hampering efforts to restore Louisiana’s disappearing wetlands, the vital buffers needed to slow the impacts of sea level rise and stronger hurricanes.

In the wake of Katrina, Louisiana adopted a $50 billion Coastal Master Plan, a sweeping strategy that outlines more than 100 projects for coastal restoration. Among the highlights: building rocky barriers to block saltwater intrusion, dumping river sediment on the banks of streams to replenish them, and constructing artificial oyster reefs to reduce erosion from waves and slow the spread of storm surge.

Multiple projects have been completed in recent years. In some places, new land is actually being rebuilt. But the $50 billion price tag is far from paid. And critics note that the strategy still fails to address the main reasons wetlands are eroding in the first place: human interference, and the continued pursuit of energy from the Gulf.

Over the last century, coastal Louisiana has lost roughly 2,000 square miles of land and continues to lose another football field each hour. Levees on the Mississippi River meant to protect residents have deprived the ecosystem of replenishing sediment. All the while, oil and gas companies have carved out more than 10,000 miles of straight, narrow canals to tap offshore reserves, allowing saltwater to intrude and erode the wetlands.

A previous attempt to force energy industry to pay for decades of damage failed earlier this year. The Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East, a levee board formed after Katrina, sued 97 oil and gas companies in 2013 for billions of dollars needed to close the rig canals scarring the landscape. A federal judge dismissed the case in February after Gov. Bobby Jindal and oil industry groups lobbied against what they called an attack on one of Louisiana’s leading economic drivers.

Efforts to redirect the Mississippi River’s nourishing waters into the wetlands are similarly contentious. Talk of “freshwater diversions” is fiercely opposed by the area’s commercial fisherman, oyster farmers and crabbers, who fret than an influx of river water will destroy the delicate balance in marine habitats and put people out of business.

The boldest proposals, to move the mouth of the Mississippi River closer to New Orleans, are politically toxic. Altering the river mouth would protect land outside the metropolitan area, but destroy communities to the south, which will likely succumb to sea level rise in coming decades.

“Everyone recognizes that you can’t begin to restore what’s been lost. The question is, what parts are going to be left out in the cold? And how much effort are you going to make to do what may be impossible?”

“It’s very much like amputating a limb where there’s gangrene,” says Barry, the former member of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East. “Everyone recognizes that you can’t begin to restore what’s been lost. The question is, what parts are going to be left out in the cold? And how much effort are you going to make to do what may be impossible?”

Whatever the future, whatever the risks, coastal Louisianans and New Orleans residents show no signs of shifting toward higher ground, or abandoning this historic and economically vital region before nature comes to claim it. In fact, the opposite is happening, as transplants arrive and former residents return.

Kelley Altazin has joined the influx to the water’s edge. A Baton Rouge native, she lived in New Orleans before Katrina, then spent the next decade in New York City and Austin. She moved into her new house in the city’s Holy Cross neighborhood, in the Lower Ninth Ward, on Aug. 7.

“New Orleans has always been home, and I never really lost my desire to live here,” says Altazin, who is in her mid-30s and works from home for a San Francisco-based startup. “There’s a different energy here now. It’s still New Orleans and it’s still funky, and there’s a lot of problems here, but I think it’s moving in the right direction.”

Holy Cross, a quiet neighborhood bordered by the Mississippi River and named for an all-boys Catholic school, was inundated during Katrina. Altazin’s 70-year-old house, which she purchased for “a song,” was flooded but not destroyed. She’s required to pay $371 in yearly flood insurance premiums for her modest home.

In the still, early mornings, Altazin navigates her new neighborhood on foot, walking with her dog to the grassy levees that shield Holy Cross from the muddy river. Where some might see vulnerability, a sign of what nature could unleash again, Altazin feels protected. The river this summer has been unusually high, and still 8 feet remains between the top of the levee and the river. She knows there are risks of floods and hurricanes, particularly in a low-lying community, but she figures that’s true of any coastal city.

“I’m worried,” she says, “and I’m not.”

Whatever the river brings next, she expects to be here to see it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.