Looking To Buy A Mine? It's A Buyer's Market As Plunging Commodities Prices Force Mining Companies To Sell Assets

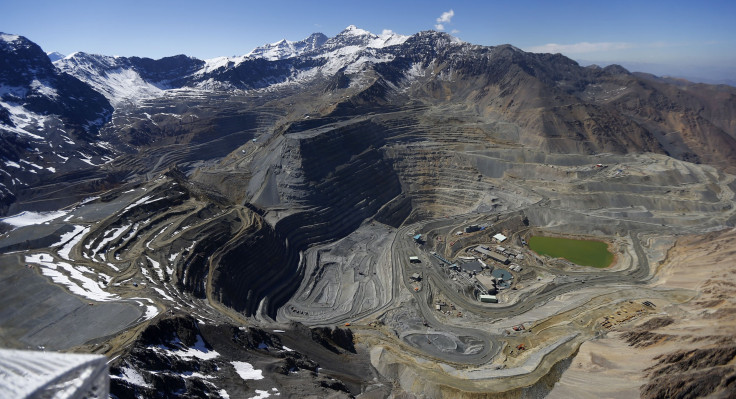

In the market for raw metals? Glencore PLC’s sprawling copper mine in the Chilean desert will set you back only $1 billion. Assuming you don’t mind a bit more of a splurge, how about Anglo American PLC’s iron ore mine in Brazil, which cost the company $14 billion to buy and build in the late 2000s? And if you’re more of a coal person, a string of mines are on the block across Australia.

It’s a buyer’s market in the global mining sector right now.

Plunging prices for minerals, metals and crude oil during the past year have hammered mining companies from Britain’s Anglo American and Switzerland’s Glencore to Australia’s BHP Billiton Ltd., Brazil’s Vale SA and the U.K.’s Rio Tinto PLC. Beset by climbing debts, deteriorating operating results and widening losses, the world’s mining giants are looking to boost their balance sheets by offloading costly assets.

Glencore said Tuesday it aims to sell between $4 billion and $5 billion in assets this year to cut some of its net debt of $25.9 billion. The mining and trading conglomerate lost almost $5 billion during 2015 as slower demand in China, supply gluts of key metals and the stronger U.S. dollar dragged down commodity prices.

Peter Archbold, head of basic materials at Fitch Ratings in London, said the number of assets for sale is climbing in part because of the cloudy outlook for China’s economic growth, a main driver of demand for copper, iron ore, nickel, oil and virtually any other material used in construction or manufacturing.

“Compared to previous downturns, there is numerically more assets for sale,” Archbold said. “There’s probably going to be a more extended downturn than in previous years because it’s related to the slowing of China, and that’s a bigger event.”

China’s manufacturing sector shrank for the seventh straight month in February, the country’s National Bureau of Statistics reported Tuesday. The manufacturing purchasing managers’ index fell to 49.0 from 49.4 in January, signaling another contraction in this sector of the world’s second-largest economy. The country’s top economic planner projected China’s economy would grow 6.5 to 7 percent this year, but the slowdown in factory activity is fueling fears of declining consumption.

In 2015, prices of copper and iron plunged 25 percent and 40 percent, respectively. And the price of crude oil, weighing on commodity prices across the board, plunged as much as 70 percent below its June 2014 peak of above $100 a barrel.

Glencore said Tuesday it expects to receive final bids this year for at least one of two copper mines, Cobar in Australia and Lomas Bayas in Chile. The South American mine has attracted offers of close to $1 billion from a handful of small, Chile-focused operators, Bloomberg News reported in January.

Among other miners, however, the selling of assets may be easier said than done.

Many mine sales to date have clocked in under $1 billion, an unattractive haul for debt-ridden miners looking to raise huge sums of cash, Archbold said. “Financial buyers are looking to get bargains,” he added.

A standoff between buyers and sellers could leave assets in limbo for years. Anglo American’s niobium and phosphate assets, which the company is hoping to sell this spring, were first slated for sale back in 2009. After Rio Tinto failed to sell a suite of aluminum operations in Australia and New Zealand, put on the market in October 2011, the company reintegrated the units two years later.

“Unfortunately for [miners], buyers’ reluctance to purchase middling assets during a savage market downturn is as inevitable as sellers’ enthusiasm to get rid of them,” Bloomberg Gadfly columnist David Fickling recently wrote.

The Brazilian Vale last week put its prime assets up for sale after reporting its biggest quarterly loss in decades. The world’s largest iron ore producer said its net loss totaled $8.57 billion in the fourth quarter, citing weak prices and large write-downs of its asset values. CEO Murilo Ferreira told reporters there were “no restrictions” on what the company would consider selling to hit its target to earn $10 billion in 18 months.

Andreas Bokkenheuser, a UBS mining analyst, told Reuters Vale had to be careful not to sacrifice future cash potential in exchange for much-needed billions of dollars now. “The question is, what valuations can they get for these assets?” he said last week.

Anglo American’s plans to sell assets worth between $3 billion and $4 billion also face headwinds. The British miner said last month its net loss doubled to $5.62 billion last year after the company faced impairment charges of $3.8 billion because of the massive rout in commodity prices.

Anglo American CEO Mark Cutifani said his company would focus only on its copper, diamond and platinum businesses and extract itself over time from its iron ore business, which includes a unit in South Africa and its $14 billion Minas-Rio project in Brazil. The firm will also exit its coal operations in Australia, Colombia and South Africa as long as buyers make good enough offers, Cutifani told investors.

Fitch Ratings and Moody’s Investor Service promptly cut Anglo American’s credit rating to junk status, citing concerns about the miner’s ability to sell its marginally profitable or unprofitable assets.

“Some of the offers for Anglo’s less profitable mines may be unpalatable for them at this point, and they may chose not to sell,” Archbold said.

Paul Gait, an analyst at Bernstein Investment Research and Management in London, said he was more optimistic about miners’ ability to offload assets. A growing pool of investors, particularly in Asian markets, are increasingly interested in snapping up natural-resources projects for their longer-term value, not just their shorter-term profitability.

“There are enough people out there that take a different view than the Western capital markets on what the intrinsic value of control of the world’s natural resources is worth,” Gait said. “Anyone with strategic vision beyond the next six months knows that control is worth something.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.