Mexican Guest Workers Who Paid Nearly $800 To Work In The US Claim Employer Didn’t Pay Promised Wages

Millions of Americans took a break from their jobs on Monday to honor Labor Day, a national holiday founded by Congress over a century ago to honor the working class. But Miguel, a 30-year-old Mexican citizen who has picked tobacco in Kentucky and cut grass on highway medians in Mississippi, says more needs to be done to ensure U.S. employers pay the wages that they report to the U.S. Department of Labor and that they promise foreign guest workers.

"I think they’re taking advantage of the situation we have in Mexico,” said Miguel, who agreed to speak to International Business Times from Mexico using a pseudonym out of concern for former colleagues currently employed as guest workers. “But they should not deceive us about the pay they're offering and pay that amount regularly."

Miguel is one of six former guest workers from the western Mexican city of Tepic, Nayarit state, who are suing two Mississippi companies they say misled them about the wages they would earn in landscaping jobs performed under contract with the state’s Department of Transportation. An amended complaint to the June 5 suit was filed last week at a U.S. District Court in Mississippi by lawyers from the Southern Poverty Law Center, who represent the workers.

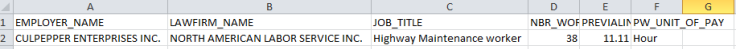

The suit against Collins, Mississippi-based Culpepper Enterprises Inc., which employed the men, and North American Labor Services Inc. in the coastal Mississippi town of Pascagoula, which recruited them, alleges the companies’ owners lured the workers with enticing hourly wage offers, but they wound up paying the workers the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.

The case also accuses Culpepper’s owner, Kathy Kervin-Culpepper, and the owners of North American Labor Services, Cheri and Jon Clancy, of violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, for conspiring to deceive the federal government and the workers regarding their pay. The RICO statute refers to the prosecution and defense of individuals who engage in organized crime. In 1970, Congress passed the RICO Act in an effort to combat Mafia groups.

John Foxworth, the lawyer representing Kervin-Culpepper and the Clancys, issued the following statement to IBTimes on behalf of his clients: “At all times, the workers were paid wages consistent with all applicable laws and regulations. Based on what I have seen, not only does there not exist any basis for civil RICO claims against my clients, but also there does not exist any viable basis for any of the claims alleged by the workers through this lawsuit.”

The companies brought these and other workers into the U.S. under the H-2B visa program, which allows employers to recruit foreign laborers for seasonal nonagricultural work. Landscaping companies like Culpepper rank high on the list of employers that use these legal seasonal laborers, along with hotel chains, seafood processors, forestry managers and construction companies. For years, employers and workers-rights advocates have been fighting over the rules of the program, but in May the advocates won a victory when the Departments of Labor and Homeland Security instituted new rules bolstering protections for these workers despite a years-long effort to block them by House lawmakers representing employers’ interests.

Still, labor rights advocates argue that a big problem with the system isn’t so much the rules as the enforcement.

Unlike the typical American worker, guest workers like Miguel often pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars to secure legal work in the U.S. And even if those costs are reimbursed by the employer, as they’re supposed to be, guest workers can’t switch jobs like local hires. If they quit, they have to leave the country immediately. This is a powerful incentive for guest workers who find out after they arrive in the country, after months spent securing a visa and paying hundreds of dollars, to simply accept the lower pay.

"You're already in the United States and if you don't like the salary change, then you have to go back,” said Miguel. “But you're there because you needed the work. I needed the work."

Federal labor law requires guest workers be paid the local prevailing wage equal to what a local hire would earn doing that job, and publicly available labor certification documents show that North American Labor Services offered $11.11 an hour for the 2014 working season. If the workers’ allegations are true, then the employer and recruiter would be guilty of submitting false wage information to the federal government.

Like hundreds of thousands of guest workers that look to the U.S. for legal work opportunities, Miguel has struggled back home to find decent employment. Millions of Mexicans reside in deep poverty and the country ranks second to last in income inequality among 34 developed economies, according to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2014 assessment.

After working for three seasons picking tobacco in Kentucky, Miguel learned from a friend about the Mississippi job. He went through a months-long application process, which included a 1,200-mile round-trip by bus from Tepic to the U.S. consulate in the northern Mexican city of Monterrey. Then the married father of two began cutting grass along Mississippi highways for Culpepper in 2011. He returned for the 2013 season and it was then, he says, that he began to realize the company had no intention of paying the wages he was offered during the recruitment process. Miguel said he returned again in 2014 because he couldn’t find any other work opportunities and because he needed the work -- even at the federal minimum wage he claims he was paid.

But by 2014, his out-of-pocket costs for working in the U.S. were rising. He claimed to have paid Cheri Clancy a $500 recruitment fee to reserve his position, a price that was higher than the previous year, as well as nearly $300 in travel and other expenses to get him from Tepic to Jackson, Mississippi. The cost of the company-provided housing went up, too. Some of this money acted as an illegal garnishment of wages that Culpepper should have reimbursed to the workers, the plaintiffs argue.

“This case is emblematic of the laws in the guest worker program and illustrate how challenging it can be to run this sort of program,” said Sarah Rich, one of the lawyers representing the workers. “[Miguel’s] suggestions were that the employers should tell the truth and employers should pay them the right wage. And, of course, that's already required under the law, and so the difficulty is in enforcing that.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.