Millennials And The Wealth Gap: What To Do When Your Friends Are Richer Than You

Last Christmas, Tiffany Belk had a mild breakdown. She always knew she wanted to put her creative writing degree to use by helping her grandfather pen his biography. So, a few years ago, she gave notice at the New York branding agency where she had worked since graduating college.

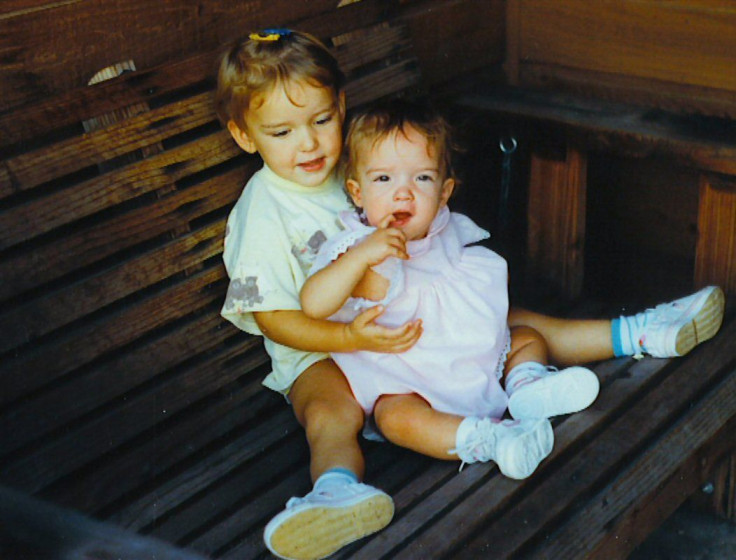

“Grandpa, I’m coming home to write your book,” she told him. The work wouldn’t pay the bills, but she planned to find a flexible job to make ends meet. To save money, Belk, 29, began living rent-free with her sister and closest friend, Lauren Hodgkins, in the home she owns on 2 ½ acres in Georgetown, Texas. A married mother of two, 30-year-old Hodgkins earned a master’s degree before landing a job as a physician assistant making $85,000 a year. That’s in addition to her husband’s oil industry job.

The vast gap between the sisters’ financial status didn’t become an issue until the holidays. Hodgkins and her husband love giving gifts and spared no expense putting presents under the tree. That’s when it hit Belk.

“I was trying to keep up and failing because I didn't have the ability to buy the big gifts,” Belk says. "Of course, they said not to worry, but it still made me feel a little insecure and inadequate that even though I wasn't paying rent, I didn't have enough saved to be able to afford high-ticket items."

The income divide between Tiffany and Lauren is striking but not unusual for people their age. Wealth inequality among millennials is more pronounced than in any other American generation. Engineering majors fresh out of college command lavish Silicon Valley salaries designing apps that feature “content” written by their poorly paid peers who studied literature. Graduates of law and business schools walk into six-figure incomes while friends struggle to make their way in nonprofit or government jobs. Teachers and social workers watch as former classmates launch venture-backed startups or climb the ranks at companies like Google.

For a select few millennials, career paths are already paved with gold. One-third of Americans who earn over $500,000 a year are under the age of 35, according to market research firm FutureCast. They exist in an income bracket dominated by lawyers, executives, engineers and entrepreneurs.

Still, the vast majority of millennials, 90 percent, make less than $60,000 a year. Slower wage growth is part of the problem, particularly among those with a bachelor's degree or less. College graduates who entered the workforce in the mid-1990s saw their incomes increase by 50 percent over their first five working years, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. Millennials who graduated in 2008 have seen their incomes rise by less than 25 percent in the same time frame.

Although wage growth among college graduates is lackluster, census data suggests it’s still better to be a millennial with a degree. The unemployment rate for millennials with a bachelor’s degree was 3.7 percent in 2013, compared to 13.5 percent for those who did not complete high school.

Among high earners, salaries and savings grow exponentially, leading to an even wider gap over time. While Hodgkins saves for the future and decides how to spend her disposable income, Belk watches every penny. “I’ve always had what I call the Walmart lifestyle, where I thought $50 purchases were extravagant,” she says.

Recently, Belk began working three days a week as a dog adoption counselor for an animal shelter. At $13 an hour, it’s a far cry from her days as a big-city professional.

Hodgkins was happy to have her sister crash in the guest bedroom, even if Belk couldn’t contribute much financially. She went grocery shopping and helped out with the child care when Hodgkins and her husband were working. Belk valued the family time but knew she needed her own place. “I felt more like a baby sitter at some points than a fellow roommate in the household,” she says. She now shares a two-bedroom apartment with a friend in nearby Austin, Texas.

For friends and family members, navigating the wealth divide can be difficult. Irene S. Levine, a psychologist and friendship expert, says that when financial differences exist between friends, it’s important to avoid money talk. That is, asking about salaries or the cost of large purchases. Allowing the income disparity to fade into the background is the best way to maintain the relationship in the long run.

“If you became friends because you shared an interest in exercise, you can take walks together or go for a hike,” says Levine. “You don’t necessarily have to climb Mount Kilimanjaro.”

Donny Gamble, a 30-year-old entrepreneur who aims to bridge the gap between the middle class and the wealthy with his investor education website, PersonalIncome.org, says making friends is important, especially if you want to follow a different path. “Hang around who you want to become. Your mind will be expanded with the things that can be accomplished,” he says.

Millennials raised on economic uncertainty may place less value on money than previous generations. “If the financial markets are going to be volatile, the most secure thing you can do is find a life and work that you love,” says Megan Hellerer, 31, a personal and executive coach in New York City and a former Google executive. “Take one action every day toward something that lights you up, even if you can't see where it is leading you,” she says.

For now, writing does that for Belk, but she wonders if she’ll feel the same way in five or 10 years. Even if she did want to change paths, she doesn’t see many options. “Sometimes it’s hard because you look at the generations before us who stayed in their jobs for 40 years and now there aren’t as many jobs where you have that stability,” she says.

Now that Belk lives on her own, she gravitates toward people who share her beliefs about money. Many of her co-workers have become close friends. Like Belk, they spend their free time focusing on artistic pursuits. Most of them do not picture a house or kids in their future.

"In a way, it’s freeing because I’ve found people taking a similar financial path to me," Belk says. "When you have money, it’s hard to comprehend the reality of living with financial constraints or that a person may be happy not making as much. This is a lifestyle choice."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.