NASA Rocket Launch Carries Mars Rover Designs Students Engineered For Space

NASA recently launched Mars rovers that students had designed, sending them into space for about 20 minutes to see how they would perform high above Earth’s surface.

The students working on the robotics project were from Virginia Tech and the University of Central Florida, NASA reported, and they used 3D printing to build the prototypes that could be used to explore Mars but would store easily, with features like folding or collapsible parts. The rocket last week sent them up 154 miles, then brought them down with a parachute into the Atlantic Ocean.

Read: Will Humans Land on This Moon of Mars?

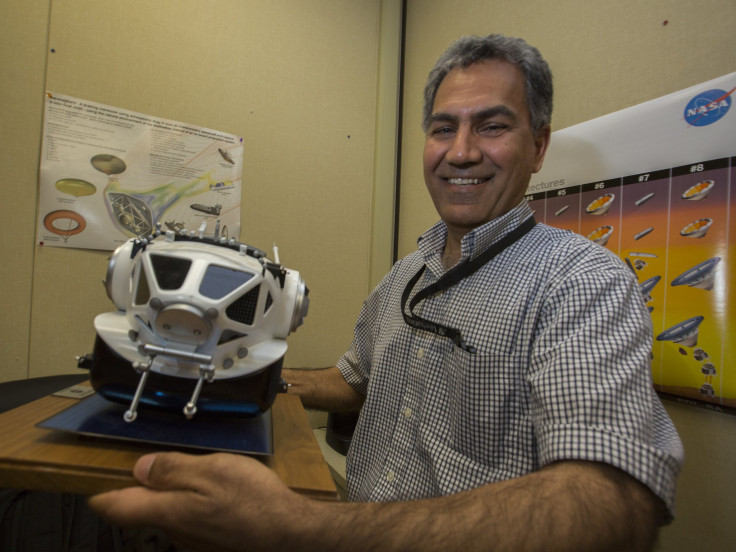

“Part of the problem we keep running into is packaging,” NASA research engineer Jamshid Samareh said in the space agency’s statement. “We have to carry a lot of payloads — rovers, habitats and such. We want to package them on top of the launch vehicle. … A rover is one the big pieces that we want to be able to see if it can be packaged in any way.”

Rovers have classically been bulky and heavy. The students helped design 18 of the more lightweight and less cumbersome Mars rovers, four of which were built and launched on the NASA rocket.

“I have always thought of mass to be the limiting factor in space travel,” Virginia Tech student Alex Matta, said in the NASA statement. “Participation in this project led me to realize that minimizing volume of the cargo is important as well.”

The students offered a fresh set of eyes and minds to the effort.

“They come up with these ideas that I cannot come up with,” Samareh said. “They have a different mentality. That worked out nicely.”

It’s not the first time NASA has sent a student’s work into space, nor will it be the last. Among other projects, the space agency plans to launch a tiny satellite next month that was designed by an Indian teenager, who calls his device the most lightweight satellite there is. It is a 3D-printed carbon fiber device weighing 0.14 pounds that could be used to take measurements of the Earth’s rotation and magnetosphere. Once 18-year-old Rifath Sharook’s satellite enters space aboard the NASA rocket, it will be tested to see how it performs in microgravity.

Still, “very few students get the opportunity to design something, put it on a NASA rocket and fly it,” Samareh said.

Read: A Space Colony on Mars Would Evolve into a New Race

While NASA commissioned the students from Virginia and Florida to design more lightweight and easily stored Mars rovers, the space agency has been working on its own projects related to that effort. Earlier this year, NASA introduced a small robot that it said was “inspired by origami,” referring to the ancient Japanese art of folding paper into a design. The robot called Puffer — full name Pop-Up Flat Folding Explorer Robot — is lightweight and could potentially be used as a companion to a larger Mars rover, either on its own or in a group of Puffers. It can fold in on itself to squeeze into tight spaces or use a tailfin as leverage to push itself upward and over obstacles. The wheels have enough traction to head up steep slopes and solar panels on its underside would keep it charged and ready to go.

But NASA robot projects don’t end on Mars — the space agency is also developing a fleet of robots that can explore icy worlds like moons in the outer solar system, melting through ice with heated prongs and cutting through it with buzzsaws and drills, and collecting samples with the help of a catapult that can be reeled back into the robot.

Whether NASA relies on the robots it is building in-house or uses the students’ designs on a trip to Mars, “there are things we learned from them,” Samareh said, “and there are things they learned from us.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.