NFL's Deflategate, Domestic Violence Responses Reveal Questionable Priorities, Victim Advocates Say

The NFL’s severe discipline of the New England Patriots for the Deflategate scandal suggests it’s worse to tamper with equipment than to physically assault a loved one. That’s the message critics and victim advocacy groups took Tuesday, when they learned that the league’s penalties against quarterback Tom Brady and the Patriots organization over the deflated ball scandal dwarfed previous actions against domestic violence violations.

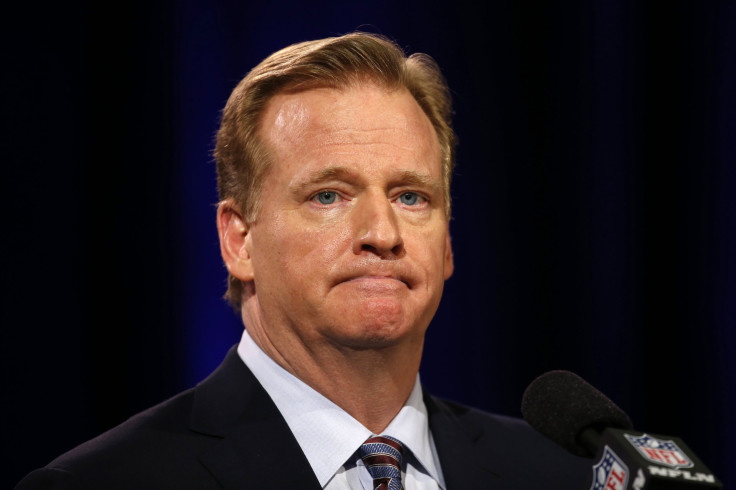

A series of high-profile domestic violence incidents involving National Football League players in 2014 led Commissioner Roger Goodell earlier this year to install widespread reforms, including a revamped personal conduct policy, and the creation of an advisory board to address policy toward such incidents in the future. But those changes took place nearly a year after former Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice knocked his fiancé unconscious in an Atlantic City casino elevator, and only after several top sponsors threatened to drop the NFL. For critics, the league’s swift, severe response to Deflategate proved it’s still more concerned with its on-field product than its players' off-field transgressions.

“That the NFL would issue more severe penalties for deflating a football than a player knocking his fiancé unconscious demonstrates how little the organization cares about family values,” said Emily Rothman, an associate professor at the Boston University School of Public Health. “The NFL seems more concerned about the health of footballs than the health and safety of women. This is deplorable, and the NFL should be held to account.”

The NFL on Monday suspended Brady for four games, fined the Patriots organization $1 million and stripped the team of a 2016 first-round draft pick after a four-month, league-commissioned investigation found it was “more probable than not” that team employees purposely deflated game balls used in last January’s AFC Championship game against the Indianapolis Colts, ESPN reports. The fine, issued despite the report’s assertion that New England’s upper management was not involved in wrongdoing, was the largest ever levied against an NFL franchise, the Associated Press reports. Troy Vincent, the NFL’s executive vice president of football operations, attributed the severe penalties to the Patriots’ perceived violation of the “integrity of the game.”

"Based on the extensive record developed in the investigation and detailed in the Wells report, and after full consideration of this matter by the commissioner and the football operations department, we have determined that the Patriots have violated the NFL's Policy on Integrity of the Game and Enforcement of Competitive Rules, as well as the Official Playing Rules and the established guidelines for the preparation of game footballs set forth in the NFL's Game Operations Policy Manual for Member Clubs,” Vincent wrote in a letter to the Patriots organization.

Disciplinary Differences

The league’s response to last year’s domestic violence incidents was far milder. Rice’s arrest for domestic violence occurred in February 2014. He wasn’t suspended until July, when he received an initial two-game ban for punching his girlfriend in the head. It took the release of graphic surveillance footage that explicitly showed Rice’s assault for the NFL to extend his suspension indefinitely. The NFL’s handling of the case and other domestic violence incidents involving Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson and former Carolina Panthers defensive end Greg Hardy generated such public outage that top sponsors like Anheuser-Busch threatened to express public concern.

Faced with financial loss, the league finally took action. By December, a new personal conduct policy mandated a six-game suspension for first-time domestic offenders and an indefinite suspension for second-time offenders. In addition to an advisory board tasked with making annual recommendations to the commissioner, Goodell vowed to hire a “disciplinary officer” to make decisions on player punishments. Rice, Peterson and Hardy were all suspended for their actions.

But when the NFL’s Deflategate punishments were announced Monday, detractors were quick to note that Brady’s four-game suspension for equipment-tampering was twice what Rice initially received for a criminal act.

“When we’re talking about a game that brought in millions and millions and there has been a pushback from people about how that game was played and [whether] the equipment was faulty, that impacts their revenue hugely,” said Ruth Glenn, executive director of the National Coalition against Domestic Violence in Washington. “The disparity between what might impact their revenue versus what might be harm to an individual is clear.”

And while the Patriots got massive fines, loss of draft picks and a public rebuke from the league office, the Ravens, Vikings and Panthers were not held accountable for their players’ violent acts away from the field. The NFL was willing to severely punish a franchise it admitted was unaware of the actions of a few rogue employees, but did not take similar action against teams that employed players accused of violent acts.

Several members of Congress asked Goodell via an open letter last February to consider punishing teams that do not adequately address domestic violence with a loss of draft picks. So far, the NFL has not taken that step.

“I commend the league for doing some important groundwork in terms of hiring advisers and doing some training,” said Cindy Southworth, vice president of development and innovation at the National Network to End Domestic Violence, a Washington-based advocacy group. “But when the consequences for battering your spouse are so much less severe than deflating a football, it sends a clear message that we have a long way to go and the NFL has a long way to go.”

Justified Response?

Others have argued the NFL had to take strong action against the Patriots. Damage to the audience’s trust in the integrity of competition – especially on such a public stage – could fundamentally upset the league’s ability to do business, said Helen Drew, a sports law expert and adjunct professor at the University of Buffalo Law School in New York.

Moreover, the league probably considered its new personal conduct policy when it levied its punishments against Brady. The Patriots quarterback may have gotten suspended for twice as long as Rice did under the league’s old conduct policy, but his four-game penalty is still less than the six-game ban called for under the NFL’s new rules against domestic violence. In that sense, the fact that Brady’s punishment was less than six games showed the league now considers domestic violence to be a more severe violation, Drew said.

In terms of team accountability, Drew pointed out that the league now requires its franchises to self-report domestic violence incidents and to participate in the subsequent disciplinary process. For NFL officials to consider sweeping penalties against a team similar to those the Patriots received in Deflategate, there would have to be obvious evidence the team’s upper management had repeatedly hired domestic abusers.

“If you get to that point, where an owner habitually employs bad actors and it starts to reflect poorly on the league’s persona, sure, they’ll consider that step. They have to,” Drew said.

But critics said punishments related to an equipment violation should not in any way surpass those meted out against individuals who cause physical and emotional damage to others. The NFL has made strides in developing an effective system to combat domestic violence, but advocates said its stance still isn’t strong enough.

“I think we will have ended violence against women when the economic, social and reputation consequences of choosing to use violence against any person, but especially a loved one, are so phenomenal that you would never think of doing it,” Southworth said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.