No Longer Number One: Shipping Crisis Hits China's Once-Roaring Maritime Industries

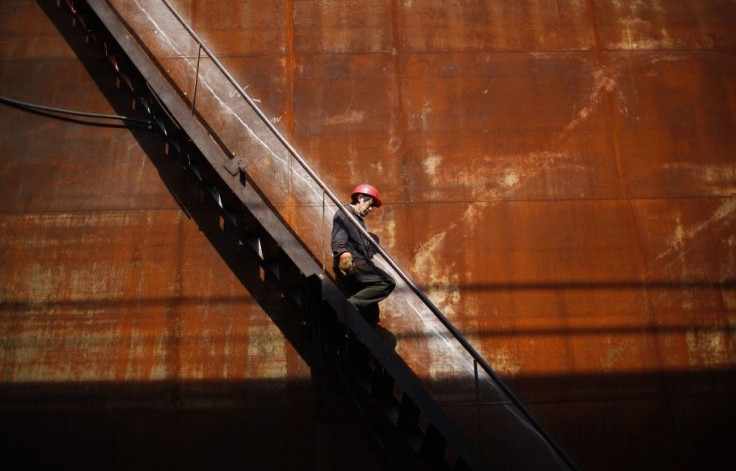

It was another industry in which where China was destined to be the world's new number one, another inexorable product of its global economic ascent. And for a while, it was. But now, two years after China overtook South Korea to become the world's largest shipbuilder, its domestic maritime industries are in decline.

China's shipping and shipbuilding industries are suffering a major slowdown, part of the losses felt worldwide by the sector since 2011. After a brief stint at the top, China returned this year to second place in the global order of largest shipbuilding nations -- a position that doesn't look likely to change anytime soon.

That's because throughout the world, major shipping companies and shipbuilders are hurting, the result of years of high production in East Asia that left a glut in the supply of container ships, bulk carriers and oil tankers; created a buyer's market for ships; and drove down shipping costs. At the same time, high oil prices pushed up up fuel costs. Shipping companies are also finding it harder to raise the funds necessary to back new orders for ships, in no small part due to economic troubles in Europe. Those factors are all working together to damage maritime industries worldwide, just as a slowing global economy reduces demand for ocean transport.

In China, the effects of this downturn are particularly apparent.

Worldwide demand for new ships is shifting to larger container vessels in order to offset transport costs. Technically sophisticated LNG (liquid natural gas) carriers and engineering vessels are also expected to be more popular. But Chinese shipbuilders, especially in the newer yards, are not experienced in building those types of complex ships. In the past, they have focused predominantly on small- to medium-size container and bulk carriers.

According to Essence Securities, a securities broker and financial consultancy in China, during the first quarter of 2012, 8 out of the 10 largest shipyards in the country received no new orders.

Worldwide, total tonnage ordered fell nearly 60 percent from first quarter of 2011 to first quarter of 2012.

The China Shipbuilding Industry Association, which monitors major shipbuilders across the country, says new orders for ships fell 40 percent during the first two months of 2012 when compared to the same period in 2011. 16 major Chinese shipbuilders recorded a loss, and overall 37 had declining profits.

UK-based Clarksons, a maritime intelligence organization, expects a 7.7 percent growth rate in international container shipping volumes this year, but that will further reinforce a condition where global shipping capacity has largely exceeded new demand.

China Ocean Shipping Group Co. (COSCO) (Hong Kong: 0517, Shanghai: 600428), China's largest shipping firm, with the world's largest fleet of dry bulk ships and sixth overall in terms of container ships operated, recorded almost 10.5 billion yuan or over $1.6 billion in net losses for 2011. That's an astonishing difference from 2010, when it had over 6.8 billion yuan or over $1 billion in profits.

A COSCO competitor, the smaller China Shipping Container Lines Co. (Hong Kong: 2286, Shanghai: 601866), had 1.6 billion yuan in losses in 2011, or nearly $250 million.

The shares for both government-owned companies have plunged from their all-time highs in October 2007. COSCO currently is one of the weakest-performing A-shares in China. According to Caixin, a prominent Chinese business and economic news agency, COSCO may now seek government money to cushion its losses.

An anonymous source told Caixin that there is a big chance that the company [COSCO] could see continuous losses in 2012, and if the company reports two consecutive years of losses, its shares will be labeled for 'special treatment' by regulators.

But the real effect would first be felt by the country's many new small-sized shipyards, which were established to take advantage of a building boom between 2004-2010. They were initially supported by the government to build China into a global maritime heavyweight, but now are targeted by authorities for closure.

Many of those new shipyards are located in the Yantgze River delta, largely in the industrial hub between Nanjing and Shanghai.

In the Yicheng area of Jiangsu Province east of Nanjing, local government officials are planning to downsize the area's shipyards from 39 to 6.

Maritime industry experts expect that facilities supported by regional governments may begin to go out of business over the following months. Some may be merged with larger companies or restructured into larger operations, but many may cease to exist altogether.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.