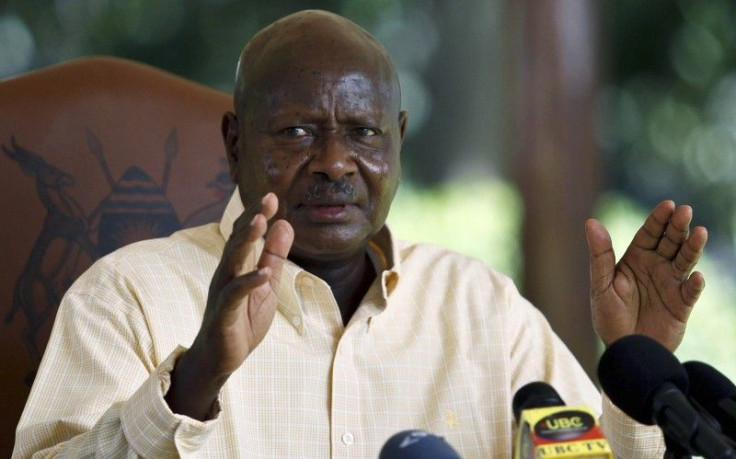

Oil, Corruption, And A 26-Year Regime: Uganda's Museveni Clings To Power After Wearing Out His Welcome

KAMPALA -- A year after winning a disputed presidential election, Yoweri Museveni, who has ruled Uganda for 26 years after wresting power as a guerrilla fighter, is facing his biggest challenge ever.

That challenge is a wave of mass protests that began in April when Ugandans, led by opposition leader and three-time presidential candidate Kizza Besigye, took to the streets to protest swelling commodity prices, soaring unemployment, and allegations that Museveni is a corrupt leader.

These complaints represent a sharp turnaround for Museveni, who was hailed as a reformer when he came to power in 1986 and was supported by the U.S. and other Western countries. At the time, he was lauded as a man who could oversee political liberalization and economic growth.

While Uganda has had many years of growth under Museveni, the economy recently has steadily worsened. Inflation was a staggering 18.6 percent in May, although it fell from 20 percent in the previous month. By comparison, inflation in the U.S. was just 1.7 percent that month.

And while the economy is still growing at a relatively fast clip, its pace is slowing: In fiscal year 2011, Uganda's gross domestic product grew 6.7 percent. But in the current fiscal year ending this month, GDP growth is expected to have slowed considerably to about 3.2 percent.

Still, Uganda's economy has a lot going for it. A landlocked country in East Africa and home to 34.5 million people, Uganda is rich in natural resources and mineral deposits. And, early in 2010, 2.5 billion barrels of crude oil were discovered here.

In years past, Museveni would have been given plenty of credit for keeping the country's economy doing as well as it is, despite the downdrafts. But his black marks are adding up so quickly that these days he gets much more blame than credit.

He has been accused of corruption, particularly in terms of campaign financing and secretive oil contracts. Last October, Uganda's parliament suspended all new deals in the oil sector after claims emerged that the U.K.-based Tullow Oil PLC paid multimillion-dollar bribes to government ministers to influence decisions.

And the Ugandan president has been charged with nepotism. His wife, Janet Museveni, was given a cabinet position as minister. His son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, is a lieutenant colonel in the army, known as the Uganda People's Defense Force, or UPDF, and commander of the Special Forces Group, which is responsible for the protection of the president.

The point is that the protests would be completely ineffective if they were not popular. What makes them popular is that people have actual grievances that have made them have made them turn out in large numbers, Besigye told journalists.

Museveni responded by threatening to eat the opposition like samosas, a reference to the Indian food popular in a country where Indians are numerous. He has followed through on that promise by unleashing his police forces onto protesters, resulting in often-violent confrontations that have left dozens dead and hundreds injured.

Arresting Developments

Despite this crackdown, the opposition isn't letting up. Hardly a day passes here without the dispersing or arresting of protesters in Kampala. This year, Uganda's Martyrs Day celebrations -- conducted June 3 of every year to commemorate a group of executed Christians -- saw scores of opposition youth violently arrested after attempting to distribute anti-government stickers during the religious festival in Namugongo, a suburb of the Ugandan capital.

Those arrests came after an incident in which women demonstrators were arrested after stripping to their bras, a radical act in this conservative country, in protest against the alleged sexual assault by Museveni's police force on a high-profile female opposition politician, Ingrid Turinawe. The head of the Women's League of the Forum for Democratic Change, or FDC, was attacked in April, according to accusers.

Now, police brutality and Museveni's decision to use force to control his opposition are fueling his fall from grace. Ugandans just want to see him gone, a notion supported by an April opinion poll by the firm Research World International: 56 percent said they wanted Museveni to resign.

Within the National Resistance Movement [Museveni's party], people have outgrown the personality of Museveni, Ugandan pollster Patrick Wakida said. They think that they can live without him. This is very interesting because now Museveni is less popular than his party.

He's also increasingly unpopular with his party. After winning a fourth five-year term, the president has squared off with legislators from his own party, the NRM, who forced him to retract a number of policy proposals, including a bill prohibiting suspects arrested during the protests from being granted bail until after six months.

The group of rebel legislators kicked off their tenure in the Ninth Parliament by drafting a bill calling for the restoration of presidential term limits -- abolished by Museveni in 2005 -- to block any attempts by the president to seek re-election when his current term expires in 2016.

They shelved the bill after the anti-Museveni protests began in April, although they refuse to say they've given up. They still may get their wish, though. Museveni told a television interviewer last month that he won't challenge the constitutional limit on governing past a president's 75th birthday -- he is 68, according to his official blog.

But protesters and NRM legislators are not alone in their desire to remove Museveni. Religious leaders have also joined the fray, urging the country's longest-serving leader to call it quits.

The best present Museveni can give to Ugandans in 2016 is peacefully handing over power, Roman Catholic Archbishop Cyprian Kizito Lwanga said at an Easter Mass; Anglican Bishop Zac Niringiye has been criss-crossing the country calling for the restoration of presidential term limits; and the Protestant Rev. Joseph Serwadda called for the incumbent president to step aside, the Washington Times reported last month.

Museveni has long been a close ally of the United States, and many voters gave him high marks for stabilizing the country and delivering economic growth after decades in which Uganda endured dictatorships and rebellion, according to a New York Times report published in May of last year.

So it doesn't come as much of a surprise that bolstering economic growth seems to be Museveni's chief concern. That was the focus of his annual State of the Nation address on June 7, in addition to scathing remarks about the opposition.

Money Isn't Everything

Uganda's economic prospects look hopeful, according to the International Monetary Fund. Contending a significant decline in inflation would lead to a relaxed monetary policy -- and the central bank has just cut its benchmark interest rate by one full percentage point -- and recovery of credit growth, the IMF forecasted this month that the economy could significantly strengthen. Growth could shoot up again to 6 percent in 2013-14 and 7 percent in 2014-15.

But that growth isn't convincing Ugandans to keep the man under whose rule the economy stabilized. Their concern is democracy.

Museveni has betrayed his promise of being a new, different leader for his country. Instead, he has resisted real democratization and resorted to acting like those he fought to replace.

That's a view shared by Uganda's powerful ally, America. In a report released in May, the U.S. State Department said Uganda is marred by a lack of respect for the integrity of the person, unwarranted restrictions on civil liberties, and violence and discrimination against marginalized groups.

That's a big change from 1986, when, in his inaugural address, Museveni said, The problems of Africa, and Uganda in particular, are caused by leaders who overstay their power. He then promised never to be one of them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.