Organic Materials On Ceres: Life's Building Blocks Discovered On Frigid Dwarf Planet

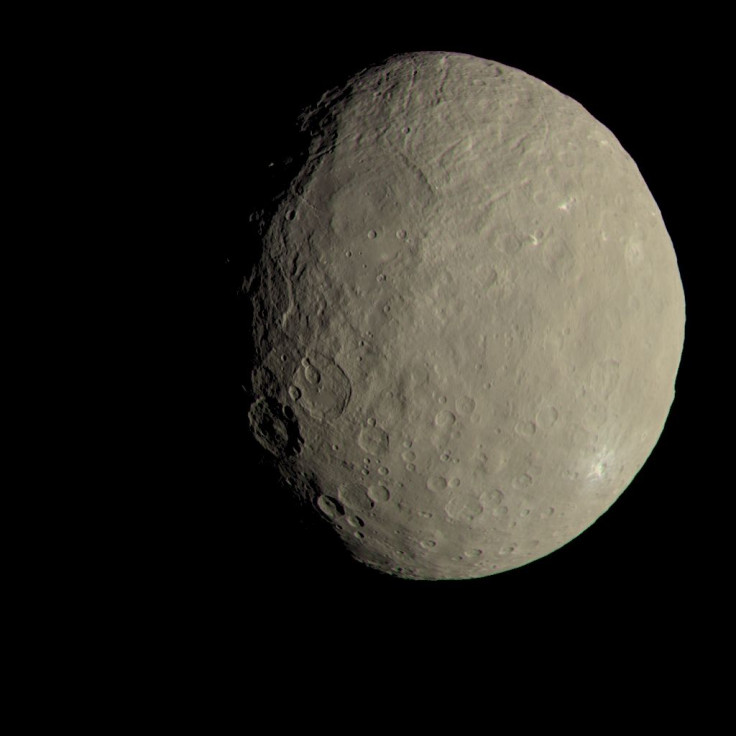

Ceres — a frigid 600 mile-wide dwarf planet — is not the kind of place you’d expect to find the building blocks of life on. But the asteroid belt object, it turns out, is a place filled with surprises.

In a study published Friday in the journal Science, a team of researchers reported the discovery of indigenously formed organic compounds — the building blocks of life as we know it — on Ceres. The organic compounds, discovered using the Dawn spacecraft’s visible and infrared mapping spectrometer, are concentrated in an approximately 400 square-mile area near the aptly named Ernutet crater in the northern hemisphere (Ernutet, occasionally depicted as a cobra-headed woman, was the Egyptian goddess of nourishment, harvest and fertility).

Organic compounds were also found in a very small area in the Inamahari crater, located about 250 miles from Ernutet.

“This discovery of a locally high concentration of organics is intriguing, with broad implications for the astrobiology community,” Simone Marchi, a senior research scientist at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and one of the authors of the paper, said in a statement. “Ceres has evidence of ammonia-bearing hydrated minerals, water ice, carbonates, salts, and now organic materials. With this new finding Dawn has shown that Ceres contains key ingredients for life.”

The fact that the organic materials are not associated with any single crater suggests that the compounds formed on the dwarf planet itself — maybe as a result of reactions involving hot water — rather than being deposited by other sources such as comets.

“The overall region is heavily cratered and appears to be ancient; however, the rims of Ernutet crater appear to be relatively fresh,” Marchi said. “The organic-rich areas include carbonate and ammoniated species, which are clearly Ceres' endogenous material, making it unlikely that the organics arrived via an external impactor.”

Moreover, given that previous observations have shown that Ceres has clear signatures of pervasive hydrothermal activity and fluid mobility, the researchers suggest that the organic-rich areas may be the result of internal processes.

However, the exact nature of the geological processes that created the organic material is still not entirely understood.

“We're still working on understanding the geological context for these materials,” study co-author Carle Pieters, a professor of geological sciences at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, said in a statement.

Since it entered into orbit around Ceres in March 2015, the Dawn spacecraft has discovered several intriguing features on its surface, including a clump of bright spots — most likely formed due to inorganic salts — near the Occator crater, potential signs of surface water-ice at Ceres’ mid-latitudes, and Ahuna Mons — a cryovolcano that erupts molten and salty water-ice.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.