Please, Do Not Urinate Everywhere: Searching For Meaning In A Whirlwind Tour Of The World

It’s late evening, somewhere over Eastern Europe. I’m sitting in the last row on an Etihad Airways flight from London to Abu Dhabi, one day into a whirlwind trip around the world. In my noise-canceling headphones, I’m switching between AC/DC and a hypnotic voice reading the Holy Quran from cover to cover, both found on the onboard entertainment system. In the seat next to mine, a bored teenager from Dubai plays with his iPhone.

Out the window, the sun is setting. My internal clock set to New York time says it’s midday. The Quran/hard-rock mashup segues into Brad Pitt's latest film, "World War Z." A multinational crew in Western dress (the men) and headscarves (the women) serves us dinner, while an announcement on the intercom lists the languages they speak between them. I stop counting at 10.

As we fly between England and the United Arab Emirates, the images inside and outside my head are a jarring collage of the unexpected and the curious, a fitting introduction to the clash of experiences that I am submitting to in the quest to go around the globe in just five and a half days.

I’m taking just a camera, a small suitcase and a notepad. I’m not stopping anywhere for more than 24 hours. I'm technically on the trail of a dying aircraft, the Douglas DC-10, whose last flights can only be found to and from Bangladesh. Meanwhile, I’m searching for messages, for distinctions and common threads in a hyper-globalized world -- all in 132 hours on and above the Earth.

I set out from New York on a Thursday night in search of the unusual, which I found even before leaving, in a Manhattan office.

Biman Bangladesh Airlines is the only airline left in the world flying the DC-10, a big three-engined jet from the 1970s that made aviation history when it helped popularize intercontinental travel along with the Boeing 747. The last two airworthy ones will be retired at the end of the year, and aviation enthusiasts are scrambling to get on the last flights. So I built my trip around two legs, Abu Dhabi to Dhaka and Dhaka to Hong Kong, flown on that classic jet. But mysteriously, the Biman website takes my Visa for only one of the flights. For the other one, I have to call the airline -- a call that turns into an invitation from the Biman representative in New York to his office, where we sip tea and chat amiably while trying to figure out what’s wrong with the website.

What Western airline would do this? Could you imagine a high-level executive for a U.S. or European airline offering you a leisurely tea on a workday afternoon? Or giving you the email address for the company’s CEO, resulting in a string of messages with more high-level managers, referring to the “Honorable Passenger” who’s trying to book a ticket? I end up buying it in Dhaka, at Biman’s ancient-looking airport counter, with a sheaf of local banknotes.

What that ticket won’t buy me, though, is a ride on the DC-10. Biman’s unfathomable scheduling changes will result in both flights, to and from Dhaka, being operated by other airplanes. From Abu Dhabi it’s a Mongolian Airlines plane, leased by Biman to supplement its small fleet, and aboard which I’m the only Westerner among the Bangladeshi passengers and Mongolian crew. A sticker on the business-class bulkhead celebrates 850 years from the birth of Genghis Khan. I wonder what the Bangladeshi passengers think of him. Do they even know who he was?

My very last chance to ride the DC-10 before it’s gone vanishes one day later in Dhaka, when I spot one parked at the gate -- but not the one I’m leaving from on the flight to Hong Kong. It’s going to Saudi Arabia instead of China. I’m left with only pictures of it, taken with my phone in the sunset after a drenching subtropical rain.

I’ve come 9,000 miles for this, and my goal is close enough to almost touch, but I can’t have it.

As I leave Dhaka, the policeman putting an exit stamp on my passport hints that I should pay him off. “Tip,” he says, “give me tip.” When I ignore him, he follows me to the check-in counter, grabbing my suitcase, talking about American dollars. In my jet-lagged fog, I lose my temper, against my better judgment: I snap at him that he’s a uniformed officer doing his duty and that I’m not giving him a penny. He retreats, suddenly meek. It’s the strangest attempt at police extortion I’ve ever seen, but I decide to count it as a minor adventure to compensate for the one I haven’t had aboard the storied DC-10.

In my 132 hours in five countries, without stopping long enough to go deep, he may be the most bizarre of my encounters. But he’s not the only one who stays with me.

There’s the immigration officer in Abu Dhabi, an Arab who greets me in perfectly pronounced Italian when he checks the birthplace on my passport. He reverts to his native language when he finds out where I’m going: “Dhaka, mashallah!” -- an Arabic expression of congratulations that his bemused tone turns into a half-disbelieving “What could you possibly want there?”

It's probably the same thing his colleague in the check-in hall asks himself when he spots the lone Westerner in a crowd of Bangladeshi passengers, and decides to open a lane just for me so I won’t have to queue up with the poor manual laborers traveling with cardboard boxes and bundles tied with twine.

There’s the Japanese passenger on the grueling flight from Tokyo to New York who sits next to me and looks puzzled when I point at the other empty seats in our row, and moves only when I ask a flight attendant to explain to him that he doesn’t have to spend 13 hours pressed against me if he can help it.

There’s the young Belgian civil servant I meet at the Dhaka airport, an airplane enthusiast even more hardcore than I, who's here for the DC-10, too, and has just come back from Iran where, because of the embargo, you can still fly vintage jets that Western airlines sent to the scrapyards a long time ago.

And then there are the children in Dhaka, where I have just a half day to walk around in search of the soul of a city of 15 million (maybe more, that’s just an estimate -- no one really knows) known for its extreme chaos. There are scores of children everywhere; Bangladesh is one of the most-densely populated, youngest countries on Earth. Sandwiched on my trip between the desert opulence of Abu Dhabi and the wealth of Hong Kong with its stylishly dressed people, it couldn't provide more of a jolt. If you're looking for an icon of the contradictions of globalization, a day in the developing world between two nights in four-star hotels in the first will provide it.

After Dhaka, landing in the spotless, hyper-modern Hong Kong airport feels like a dream. The city itself replaces the sensory assault of a Bangladeshi megacity with the thick smog of a Chinese metropolis, and still manages to turn the yellow industrial haze into great beauty.

On my last full day in Asia, before flying to Tokyo and making my connection to New York, I decide to go on the hunt for the only two things I have time for: Good Chinese food and strange signs in cockeyed English, both plentiful in these parts.

My hotel room tells me to insert my room key here to gain power. I obey; the lights come on; I gain no power whatsoever, but I do smile.

All through this trip, I’ve been thinking in Italian while speaking English, courtesy of the Italian novel I’m reading on flights, and then Italian appears incongruously on a Kowloon street, in the form of lurid magazine covers outside an Italian restaurant. Supermarket tabloids from my youth. More weirdness.

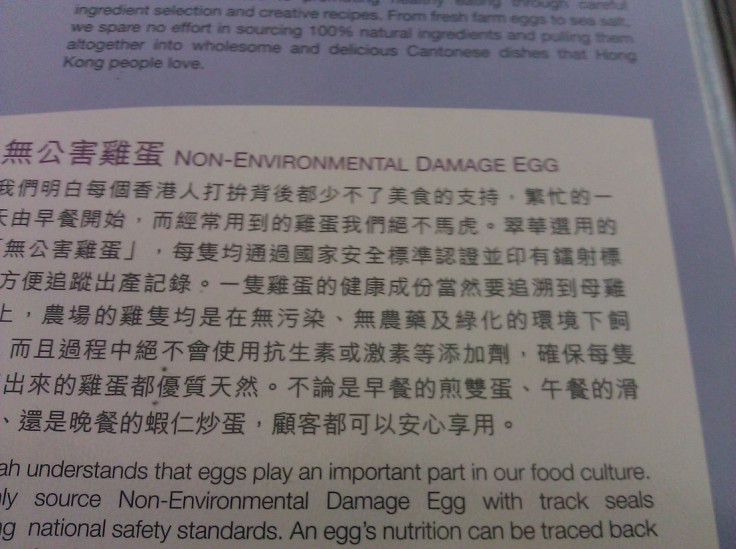

At the noodle house where I sit down for lunch, the menu is an exercise in the fantastic, casual poetry that results from Chinese transliterated to English by non-native speakers: Besides "cpork,” it offers a mysterious “money belly” and the phenomenally named “queen of fresh leisure.” There are entire websites devoted to the delightful absurdity of this uniquely Asian lingo, and now I’m inside one of them, a living example of the bizarre consequences of the adoption of English as the globalized world’s language. (Fair warning: Those sites can contain very explicit language).

Later, strolling through the Tsim Sha Tsui neighborhood, I spot another sign, one whose sheer weirdness seems to tell me: The world you're crossing may be very small, but it'll never lose the power to amaze you with its differences. Just when you think you're walking through a perfect twin of your New York, a metropolis of American-dominated commerce, you'll see something that sounds like home but will make you realize that you couldn't be farther from the familiar.

It could be the dizziness from Hong Kong’s brutal smog going to my head, or the vertigo from the 12 time zones I’ve crossed at a running clip, or the feeling of being in a fast-paced remake of writer-director Sofia Coppola’s "Lost In Translation." I’m not sure. But when I’m done laughing, I realize that maybe the search for a meaning in the ultra-globalized world ends here:

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.