Ken Salazar Working For Anadarko After Promising To Honor Federal Ethics Law

Former U.S. Interior Secretary Ken Salazar has been working for a major oil and gas company as it has sought to limit political damage after a deadly explosion near one of its Colorado wells, a spokesperson for Colorado Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper and emails obtained by International Business Times and MapLight say.

One of his state’s most powerful Democrats, Salazar was in touch with Hickenlooper’s office after the blast on behalf of Anadarko Petroleum — a company Salazar helped when he ran the Interior Department under former President Barack Obama.

Salazar, a corporate lawyer, has previously said he would honor federal ethics laws by walling himself off from matters in which he was involved at the agency. Emails show he has been working for Anadarko in Colorado though he has not registered to lobby for the company there, state records show.

Anadarko, Salazar and his law firm, WilmerHale, did not respond to repeated requests for comment from IBT/MapLight.

Hickenlooper has ordered a statewide review of all oil and gas lines in Colorado that lie within 1,000 feet of an occupied building, and he is currently weighing whether to support disclosure legislation against which Anadarko successfully lobbied in the days after the calamity in Firestone, Colorado. That bill — which Colorado Republican lawmakers recently blocked after Anadarko donated to a political group supporting them — would have forced oil and gas companies to release maps telling homeowners how close they live to oil and gas lines.

Hickenlooper, a former oil industry geologist, has in the past helped the fossil fuel industry try to thwart regulatory measures. On the disclosure bill, Hickenlooper said he generally supports more transparency, but he has wavered on whether he believes the legislation is necessary, saying, “I’m not compelled that it’s got to be the state that controls that.”

State records show Anadarko in 2017 successfully lobbied against not only the disclosure legislation but also against two other bills designed to restrict fracking and drilling in Colorado.

On April 26, authorities investigating the Firestone blast confirmed they were looking at an Anadarko well near the home that exploded. That day, Anadarko general counsel Amanda McMillan contacted Hickenlooper chief legal counsel Jacki Melmed about the situation. “I understand that you’ve spoken with Ken Salazar, who suggested that I reach out and connect with you,” McMillan wrote in an email.

Jacque Montgomery, a spokeswoman for Hickenlooper, told IBT/MapLight that Salazar “identified himself as Anadarko's counsel.” She said Salazar was alerting the office that the company would be issuing a news release to explain the actions it had taken after the explosion.

A separate email from an Anadarko official to another Hickenlooper aide said: “Al and others on our team have spoken with the governor.” Hickenlooper’s office confirmed to IBT the governor spoke to Anadarko CEO Al Walker after the explosion.

Salazar’s History With Anadarko

Salazar, a former U.S. senator and state attorney general, was the transition team director for Hillary Clinton’s unsuccessful 2016 presidential campaign. He recently announced he will not run for governor in 2018.

His law firm, WilmerHale, has ties to Colorado oil and gas regulators. Salazar’s firm bio says his “law practice is focused on corporate governance, energy, environment and natural resources.”

As interior secretary, Salazar led a department that oversaw Anadarko — and at times helped the company.

In 2010, McClatchy reported Salazar’s department waived environmental rules for an Anadarko offshore drilling project after the Deepwater Horizon spill even though Anadarko partially owned the well involved in that disaster.

Salazar and his agency approved a 2012 plan to let the Anadarko develop as many as 3,600 new gas wells in eastern Utah. Although the deal was touted as a victory for the economy, U.S. government and environmental groups, both the Bureau of Land Management and the Utah Department of Environmental Air Quality have raised concerns about air pollution from wells in the region.

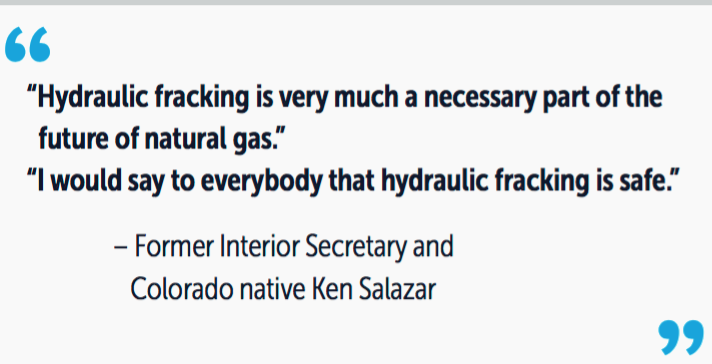

In its promotional materials, Anadarko has touted Salazar’s support for fossil fuel development. “Hydraulic fracking is very much a necessary part of the future of natural gas,” the former Interior Department chief was quoted as saying in an Anadarko fact sheet. “I would say to everybody that hydraulic fracking is safe.”

The document also quotes Hickenlooper as saying: “Fracking is good for the country’s energy supply, our national security, our economy and our environment.”

Another Anadarko fact sheet quotes Salazar celebrating the Utah natural gas project.

‘Core Revolving Door Problem’

When Salazar left the Interior Department, he told the Houston Chronicle “a number of walls may have to be erected” to prevent conflicts of interest in his private sector work. He specifically said that because of his involvement in the Deepwater Horizon spill, he made an arrangement to be “permanently walled off from any BP work and money, now and forever” — but he did not say if that wall included other firms like Anadarko that were also linked to the leak.

Under federal ethics rules, Salazar was not permitted to lobby the federal government for two years on behalf of any client. The rules also permanently bar Salazar from working in the private sector on a particular matter involving specific matters in which he participated during his time leading the Interior Department.

Those rules, however, only cover the federal government, not state officials.

In recent years, former elected officials have been criticized for failing to register as lobbyists even as they work for companies on public policy matters. Salazar has not registered as an Anadarko lobbyist, even though Colorado lobbying rules are generally designed to compel registration from those who are pressing public officials on behalf of companies.

While the state’s lobbying rules cover the governor’s office, they only apply in fairly limited scenarios. Luis Toro, the director of Colorado Ethics watch, said the state’s definition of lobbying is “pretty narrow,” and that individuals must “urge an action on legislation” to qualify as a lobbyist.

"Salazar going from ostensibly protecting the environment to working for a major oil company is likely legal, but it is certainly shameful,” said Jeff Hauser, who runs the Revolving Door Project, a group that has pressed for tougher ethics rules. “The core revolving door problem is people spending time in government service supposedly regulating corporate misbehavior in the public interest while knowing that they will be protecting those very same corporations once they get out of office.”

“Just because Salazar's previous office was federal and his current efforts are focused on state government officials doesn't make the 180-turn away from environmental protection to corporate enrichment any better ethically,” Hauser said.

This story is a collaboration between International Business Times and MapLight, a nonpartisan nonprofit that reports on money in politics.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.