For Years, Chemical Industry Has Pressured Government To Defund Key Chemical Incident Database

As President Trump attempts to shut down a federal board that helps oversee chemical plant safety, a former top official from the panel says the unfolding crisis at a Houston plant could have been prevented had the plant owner's lobbying group not fought the board's work.

In 1998, when the Chemical Safety Board (CSB) was formed, Chief Operating Officer Phyllis Scalettar led the team in creating a comprehensive database of chemical incidents, relying on data from five different federal agencies. The CSB created the database — which was the first of its kind — because officials believed a central resource documenting all incident reports, especially relevant information on what caused the incidents, was vital for the board to fulfill its mandated duty: to investigate toxic chemical incidents and determine the causes of those incidents.

When the CSB published its one-of-a-kind report in February 1999, analyzing data from 600,000 chemical incidents over a decade, and presented it to Congress, the feedback was positive. But when the American Chemistry Council (ACC) got hold of the report, the group hurled accusations of bias at the nonpartisan CSB in an effort to discredit the report. An influential lobbying and campaign spending operation, the ACC successfully pressured Congress to withhold sufficient funding for the CSB, preventing it from updating and enhancing the crucial database.

Arkema — a specialty chemicals company whose plant in Crosby, Texas, exploded last week and which pressed regulators to kill a chemical plant safety rule — is a member of the ACC.

The Chemical Safety Board planned a follow-up report for the 2000 fiscal year, but it never happened.

“Perhaps, had the report led to the envisioned subsequent work, risks that now pose current threats to the Houston area — and, indeed, throughout the U.S. — could have been evaluated and addressed prior to the disaster in a comprehensive, data-driven manner,” wrote Scalettar in an email to International Business Times.

Going forward, an underfunded CSB would not be able to harness an updated database to help prepare for, and prevent, the tens of thousands of chemical incidents that occur every year in the U.S.

Scalettar confirmed there is no current central resource in the U.S. for information on preventing chemical incidents.

The CSB still exists, but it continues to be hampered by what officials say are insufficient resources.

In April 2013, investigations into 13 prior chemical incidents were incomplete. CSB leadership told the Center for Public Integrity at the time that the budget allocated by Congress wasn’t nearly enough to tackle the numerous incidents. "We've made innumerable proposals over the years...pointing out the significant discrepancy between the number of serious accidents and the ones that we can handle from a practical standpoint," said CSB managing director Daniel Horowitz.

The chemical industry, led by the ACC, has for years fought legislation requiring chemical facilities to use safer technology.

"I was quite surprised that anyone would resist this concept, this concept of prevention," Rafael Moure-Eraso, then the CSB chairman, told NPR in 2013.

“You have to make a cost-benefit about what is more costly: to engage in a process to try to mitigate or avoid hazards; or deal with the families of the people who get killed, the destruction of an industry, the destruction of a community," said Moure-Eraso. "And I claim that it's a lot more expensive to deal with these catastrophic losses than what it will take to invest to prevent this to happen in the first place."

Tens Of Thousands Of Chemical Incidents Each Year

In 1990, Congress amended the Clean Air Act to enhance its efforts to reduce acid rain, urban air pollution and toxic air emissions. The amendments established the Chemical Safety Board “to investigate accidental releases of chemicals.” In particular, the board was created “to determine the cause or causes of an accident whether or not those causes were in violation of any current and enforceable requirement.”

It took more than seven years — until January 1998 — for the government to staff, fund and launch the board. When board finally began its work, its first order of business was to study the hundreds of thousands of prior chemical incidents across the country and analyze the reasons that these incidents had occurred.

“Most importantly from a safety standpoint, existing databases do not contain information on the root causes of incidents or patterns of causes that are the most solid clues to prevention,” the report states.

A 1993 EPA report admitted that the government’s chemical safety system was full of “overlaps, inefficiencies, and some gaps in the statutory and regulatory framework as well as in the government's management structure.” It also states that “sufficiency and quality of government data on chemical incidents impact ... most importantly, lives and livelihoods.”

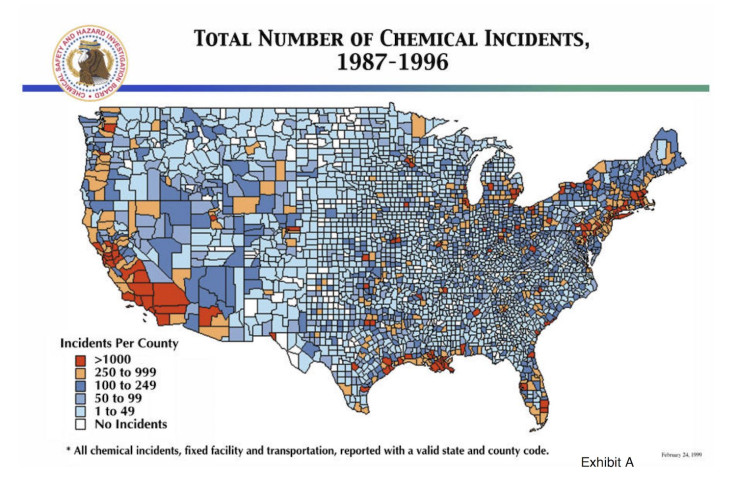

CSB staff members began their research with over 10 million chemical incidents that occurred on land between 1987 and 1996. After filtering out duplicate incident reports and those that contained insufficient information, the board was left with 605,000 incidents to incorporate into its study, which came out in 1999.

Some key findings include:

—During the period 1987 to 1996, chemical incidents were recorded in 95 percent (3,145) of the nearly 3,300 U.S. counties.

—42 percent of the incidents occurred at fixed locations occupied by industrial and commercial businesses, and 43 percent related to transportation.

—9,705 incidents resulted in at least one death or injury. There were 2,565 deaths (with an average of 127 incidents per year resulting in at least one death) and 22,949 injuries.

—California had the most incidents (100,000 during the period from 1987 to 1996), nearly double the number of incidents recorded for Texas (55,209), the second leading state. The remainder of the top 10 states, in descending order, were Ohio, New York, Louisiana, Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Florida and New Jersey.

—Mechanical failures led to 40 percent of the incidents. Intentional and unintentional human acts were cited in another 27 percent of the reports. The effects of natural phenomena accounted for only 1 percent of the incidents. Approximately 29 percent of the incident reports did not indicate an initiating event.

A more recent study of the period from 1980 to 2008 indicates that 3 percent of hazmat emissions occurred due to natural phenomena, and these nature-induced emissions increased as the years passed.

The ACC waged a campaign against this report.

“The industry association challenged the accuracy of the reporting data used in the study, failing to recognize and acknowledge that the data were reported by the industry itself,” Scalettar told IBT. “It also pointed out the data limitations referenced in the report undermined the findings, again overlooking the fact that identification of limitations in any research study are fundamental to establishing that claims made are not misleading, and recommendations for future work are supported by the issues raised.”

Scalettar added that “because our [CSB] board was populated by some people who had strong attachments to industry, I would be remiss not to say that there was probably some back-room arm twisting.”

Freedom of Information Act Request records show that the ACC submitted comments regarding the EPA’s risk assessment practices, discouraging the consideration of worst-case scenarios and “biased risk assessments.”

Meanwhile, in 2001, the ACC and similar industry groups successfully convinced the George W. Bush administration to kill chemical safety provisions proposed by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, including a strengthened Process Safety Management standard.

An Arkema Disaster

Included in the CSB report was a map showing all chemical incidents analyzed. Many chemical incidents that occurred between 1987 and 1996 were located in southern California, but another area with one of the highest concentrations of explosions, emissions and other hazardous events was the southeastern coast of Texas, which is where Hurricane Harvey hit.

Nearly 20 years after that report, Arkema North America’s CEO said that “no one anticipated six feet of water” that Harvey brought to his plant in Crosby. But Sam Mannan of Texas A&M University's Mary Kay O'Connor Process Safety Center told the Houston Chronicle that it would be surprising if Arkema had not considered a flood of this magnitude before. And there was a way to prevent the explosions: Companies can “quench” organic peroxides by combining them with another chemical, potentially eliminating the danger.

"You'll lose the feedstock, but it's safer than letting it go into runaway mode," Mannan told the Chronicle.

As IBT reported on Saturday, Arkema warned its investors of the risks of chemical storage explosions at its sites.

Arkema’s most recent risk management plan submitted to the EPA is from June 2014; the facility has high levels of toxic chemicals, making it a Program 3 site that is required to file such plans with the EPA. The Environmental Defense Fund reviewed Arkema’s plan, which the public may only inspect in person in an EPA reading room. That plan, which revealed that the facility held 85,000 pounds of the flammable substance 2 methylpropene and 66,000 pounds of toxic sulfur dioxide, cited a 2013 hazard analysis that identified concerns including “equipment failure; loss of cooling, heating, electricity; floods (flood plain); hurricane; other major failure identified: power failure or power surge.”

On Friday, after several explosions had already occurred, Arkema announced that least 225 metric tons of peroxides stored at its Crosby plant were likely to explode in the near future.

The company has a history of dangerous chemical safety practices, including “serious” hazardous chemical-related safety violations in February by the Arkema plant in Crosby, resulting in a $90,000 fine from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Trump’s Attack On Chemical Safety

As IBT reported Thursday, Arkema and the ACC successfully lobbied the EPA to halt new chemical safety rules that were meant to go into effect in March 2017. Numerous U.S. Congressmen from Texas co-sponsored a House resolution to quash those rules. Previously, then-Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sent a letter to the EPA expressing their opposition to the safety measures.

This year, as EPA director, Pruitt has been able to delay the implementation of the safety rules twice, and as Crosby residents were evacuating due to Arkema’s plant explosions, a court denied environmental groups’ request to impose the rules as a lawsuit over the delay moves through the courts. But there are even higher-ranking officials who are trying to minimize chemical safety: Trump’s budget proposal would eliminate the CSB altogether, something that has elicited serious criticism.

“If you want to put the American people in danger this is the way to do it,” former EPA director Christine Todd Whitman told Reuters. “The chemical industry has fought back from the beginning.”

“If you can’t prove your relevance in today’s administration, you become superfluous,” said Scalettar. “Can [the CSB] show they’ve made any significant progress in reducing chemical incidents? Probably with great difficulty.”

With the current Congress and White House, Scalettar doesn’t paint a rosy picture of the near future. “There will continue to be chemical incidents, but we could make the circumstances a little bit better. But after 20 or 30 years at this, I’d say the odds aren’t very good to make it better.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.