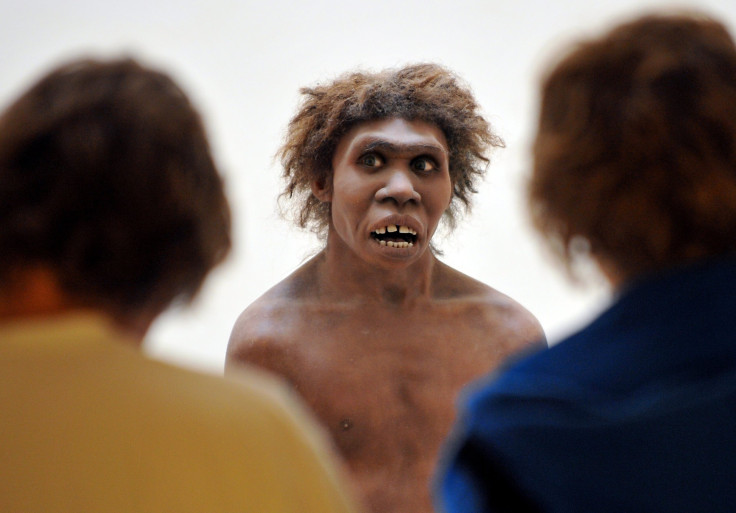

Prehistoric Humans' DNA Reveals New Clues About Neanderthals’ Evolution

How did Neanderthals evolve? How did their population dwindle, eventually causing them to die out? In order to address these questions and other mysteries surrounding the evolution of Neanderthals, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, sequenced the genomes of five Neanderthals. The new study has helped researchers figure out some details about the last remaining Neanderthals that lived in Eurasia.

The Neanderthals whose genomes were sequenced lived between 39,000 and 47,000 years ago and came from different geographical regions. These Neanderthals once lived in what is present day Belgium, France, Croatia, and Russia and represent the group of last survivors in Europe.

The genomes of these five Neanderthals were compared to those of older ones, who once lived in the Altai Mountains. Scientists discovered that these late Neanderthals are far more closely related to their later cousins who contributed DNA to our modern ancestors, than to the older Neanderthals.

The genomes of the five Neanderthals also provided clues about a turnover in their population, as these ancient hominids’ existence slowly came to an end.

“We see that the genetic similarity between these Neandertals is well-correlated with their geographical location. By comparing these genomes to the genome of an older Neandertal from the Caucasus we show that Neandertal populations seem to have moved and replaced each other towards the end of their history”, Mateja Hajdinjak lead author of the study, said in a statement.

Researchers also compared the Neanderthals’ genomes to modern humans, living today, which reinforced their discovery of these Neanderthals’ DNA being more similar to those who contributed DNA to modern-day humans living outside Africa than older ones who lived in Siberia.

Scientists also discovered that despite four of these late Neanderthals having lived in an era when modern humans had already begun living in Europe, none of them had any detectable amounts of modern human DNA.

“It may be that gene flow was mostly unidirectional, from Neandertals into modern humans”, said Svante Pääbo, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“Our work demonstrates that the generation of genome sequences from a large number of archaic human individuals is now technically feasible, and opens the possibility to study Neandertal populations across their temporal and geographical range”, said Janet Kelso, who co-authored the new study.

Since there are only a limited number of Neanderthal specimens available at present and obtaining DNA from such old specimens can be a challenge, there are very few Neanderthals whose genomes have been sequenced. However, the new research has added five additional new Neanderthal genomes from a wider geographical range, which may aid further research into these prehistoric ancestors of modern humans.

The new study has been published in the journal Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.