Hurricane Katrina Anniversary: 3 Ambitious Plans To Save New Orleans From Climate Change

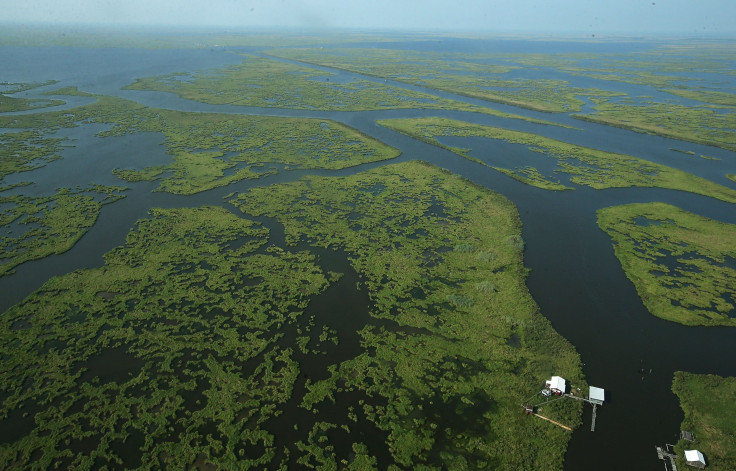

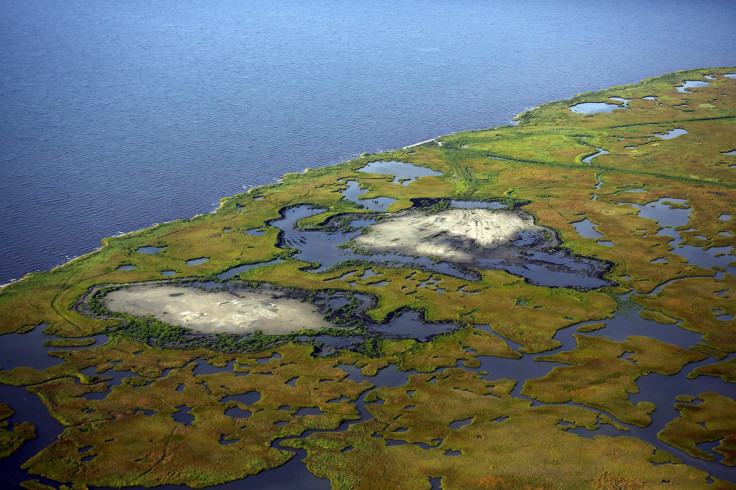

Coastal Louisiana is under mounting threat from the forces of climate change. And yet the region’s best defense against rising seas and stronger storms -- the wetlands -- is rapidly vanishing into the Gulf of Mexico. Lush swamps and marshes that once surrounded houses and fisheries are dissolving into scraggly patches of green, brown and blue, shrinking the vital buffer zone between communities and the water.

Hurricane Katrina made it clear how far the region has to go to protect from powerful storm surges and catastrophic flooding. The storm pummeled New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005, and shattered the city’s faulty flood defenses, racking up around $100 billion in damages and causing over 1,800 deaths.

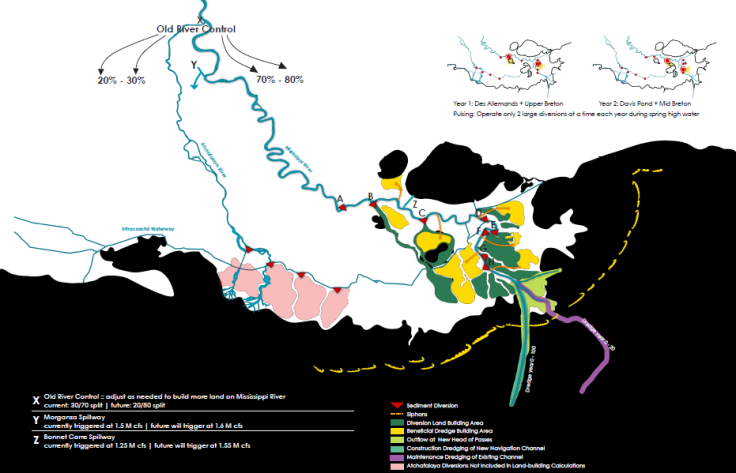

As the 10th anniversary of Katrina nears, coastal scientists, engineers and planners are pushing three ambitions plans to save Louisiana from sinking over the next century. By redirecting the Mississippi River, dredging sediment and building new deltas, they aim to stem the dramatic wetland loss eating away at Louisiana and turn open waters into thriving swamps. At the same time, they propose gradually moving towns and industries upriver and away from the coast to reduce the number of people and investments exposed to climate risks.

The three strategies are part of the Changing Course design competition run by regional and U.S. environmental groups. The winning teams -- Baird & Associates, Moffatt & Nichol and Studio Misi-Ziibi -- presented their plans Wednesday in New Orleans during a weeklong series of events on Louisiana’s post-Katrina recovery.

The competition grew out of Louisiana’s $50 billion Coastal Master Plan, a sweeping strategy developed after Katrina to start protecting coastal communities from climate risks. The 50-year plan is filled with short-term projects to regenerate land and slow the spread of storm surge. But it left a critical question unanswered: How could Louisiana harness the Mississippi River to build the most land possible?

“It’s from that question that Changing Courses was born,” said Steve Cochran, a member of the Changing Course team and associate vice president of ecosystems at the Environmental Defense Fund. “We hope the winning ideas will help citizens, communities, industries and governments engage in real conversations about what it’s going to take to make this important region more resilient and prosperous.”

Coastal Louisiana has lost nearly 2,000 square miles of wetlands since 1932, the result of levees built along the Mississippi River and rig canals dredged by offshore oil and gas companies. The development has permanently disrupted the ecosystem, starving the marshes of river sediment and allowing corrosive saltwater to intrude. If nothing is done to fix the problem, as much as 500 square miles -- enough land to fill Los Angeles -- could erode by 2030.

To stop that, all three Changing Course strategies propose shrinking the river delta zone and moving the mouth of the river closer to New Orleans. The measures would fortify the densest and most inland communities while leaving other areas to wither away.

Here’s a look at the three winning plans:

1. “A Delta For All” (Baird & Associates)

This team is proposing to split the ends of the Mississippi River into multiple outlets, which would deposit sediments into sub-deltas filled with wetlands and solid ground. Under the strategy, the outlets would be turned on and off like faucets at 50-year intervals, concentrating land-building in certain areas and preserving the saltier areas critical for fish, crab and oyster habitats.

2. “The Giving Delta” (Moffatt & Nichol)

This proposal includes eight land-building strategies, including creating controlled “flood-pulse structures” upriver and downstream of New Orleans that pump sediment-rich river water into upper coastal basins. Sediment-capturing basins at the main stem of the river, combined with “sand engines” that harness wave energy and distribute sediment, will further spread land-building ingredients across the river delta.

3. “Living Delta” (Studio Misi-Ziibi)

This third plan would reconstruct and transform the ecosystems along the river delta. In the upper reaches of the system, near and above New Orleans, new swamps will be built and old ones fortified. Freshwater marshes will develop in the intermediate areas, while brackish salt marshes will develop in the outermost areas in the Gulf. This strategy involves scooping up river sediment and dumping it in the delta, building pipelines to siphon dredge material, and diverting freshwater to naturally replenish the wetlands.

Despite the ambitious visions, turning these three land-building plans into a reality may prove a monstrous task for experts, officials and residents. Each strategy will require billions of dollars and decades of sustained political attention to complete. Yet long-term projects with delayed results are easily shelved when competing with short-term budget needs and continuously changing leadership.

The biggest obstacle is the issue of moving people and industries to the north. Centuries of family history and culture are woven into the fabric of Louisiana’s coastal region. Many people here are reluctant to abandon their homes and heritage for higher ground. Commercial fisherman and oil-and-gas workers need to live on the water to do their jobs. And plenty of families simply can’t afford to pack up and move. Those communities are not likely to easily swallow a plan that would abandon their areas while salvaging New Orleans.

“If you could preserve everything, of course you’d want to do that. On the other hand, it’s not clear those areas could be preserved under any circumstance,” said John Barry, who served as a member of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East from 2007 to 2013 and was not involved in the design competition. “The only justification going forward is that you can’t save them anyway, no matter what you do,” he said. Still, he added, “it may be politically impossible.”

Cochran, from the Environmental Defense Fund, said the three design teams considered this dilemma. Their plans call for “real engagement of communities in making their own choices about managing the future, rather than having it handed to them.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.