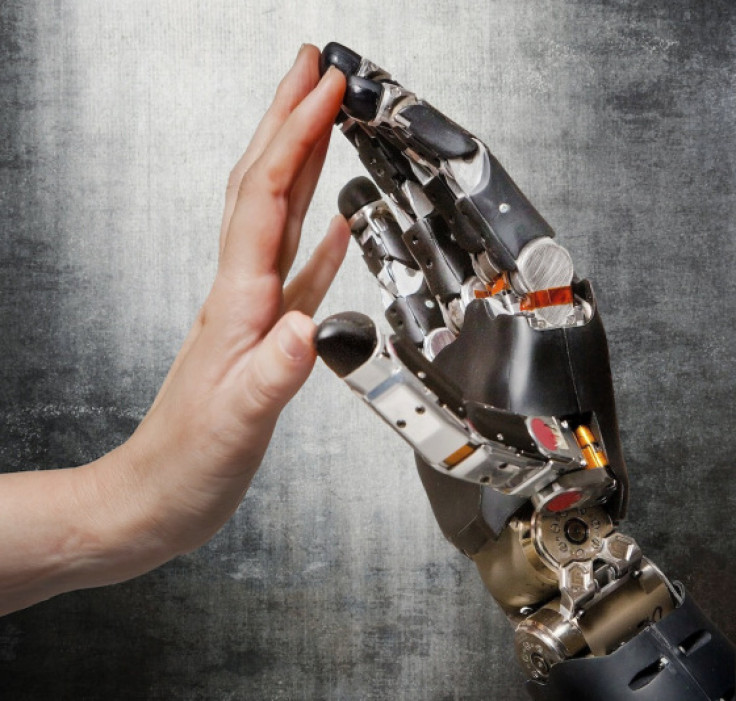

Restoring Touch: Researchers Develop A ‘Blueprint’ To Add Sensory Feedback To Prosthetics

Prosthetics are getting closer to mimicking human function, but the loss of touch is one of the biggest hurdles researchers need to overcome. In a new study, researchers from the University of Chicago have developed a “blueprint” that could pave the way for real-time sensory feedback.

The development of a sense of touch in prostheses could be developed in the same way as mind-controlled artificial arms and limbs. The University of Chicago said in a statement that the sense of touch lets humans differentiate between objects and textures while also informing our grip and other parts of our daily routine. Prosthetic hands have advanced to the point where grip can be adjusted and fingers are individually powered and articulated, but they still lack the sense of touch.

The new research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Sliman Bensmaia could pave the way to add touch to prostheses, making artificial limbs feel like a “natural extension of our bodies.” The blueprint to restore touch was developed by analyzing monkeys and was inspired by previous work developing a direct interface linking the brain to the prosthetic.

Bensmaia is trying to reproduce touch by stimulating the brain to recreate how a human processes sensory information. “To restore sensory motor function of an arm, you not only have to replace the motor signals that the brain sends to the arm to move it around, but you also have to replace the sensory signals that the arm sends back to the brain,” said Besmaia in a statement.

Using monkeys, due to their similar sensory systems, the researchers isolated neural activity that was associated with object manipulation, contact and pressure, successfully recreating that pattern artificially. For contact, the researchers trained the monkeys to respond to physical contact, later attaching electrodes to stimulate parts of the brain associated with individual fingers to recreate contact through artificial means. The monkeys responded to artificial contact in the same way they responded to actual contact. The researchers developed a system to recreate the sensation of pressure, once again successfully stimulating parts of the monkey’s brain to artificially create that sensation while also recreating neural activity associated with first touching, or releasing, an object.

These three experiments were then developed into a set of instructions that could recreate a sense of touch. A neural interface within the prosthetic arm would provide feedback to the brain, simulating the necessary parts of the brain and artificially creating a sense of touch. The next step would be developing prototypes and conducting clinical trials.

Recently, a team of engineers from the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago developed a prosthetic limb that could be controlled by an individual’s thoughts. The 32-year-old male amputee controlled the prosthetic leg by thinking about the movement and those signals, found in the thigh muscle, which were then translated and coupled with data collected from sensors on the prosthesis. This data was interpreted to replicate movement such as transitioning between stairs and level ground to adjusting leg position while seated.

The research involves creating a network that would connect these different functions and is a part of the Revolutionizing Prosthetics project funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, DARPA. The project is currently researching thought-controlled prostheses and improving the speed, movement, dexterity and overall intuitiveness of artificial limbs.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.