Rodney King And The LA Riots, 25 Years Later: The Video That Changed Everything — And Nothing

Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old shot in a Cleveland Park because police thought he had a gun, his death caught on surveillance video. Eric Garner, killed by police who held him down while he gasped “I can’t breathe,” in Staten Island, New York, while a bystander nearby captured his last moments. Walter Scott, pulled over during a traffic stop and shot by police in South Carolina as an eyewitness recorded video. Philando Castile, fatally shot inside his car during a traffic stop in Minnesota, the shooting recorded by his girlfriend in the seat next to him. Terence Crutcher, killed outside his car in Oklahoma, the shots captured on video by a police helicopter.

And Rodney King, whose beating by police was recorded a quarter-century ago. Those nine minutes of footage ushered in a new era of viral video that has become almost a staple of the modern news cycle.

“That video could have been shot yesterday in Chicago,” Jeffrey Cramer, a former federal prosecutor and managing director of the Berkeley Research Group in Chicago, told International Business Times.

Despite a two-decade pile-up of disturbing images, young African-Americans remain vulnerable to police violence. In 2016, U.S. police killed at least 258 black people — 39 of them unarmed, according to a tracking project by The Guardian.

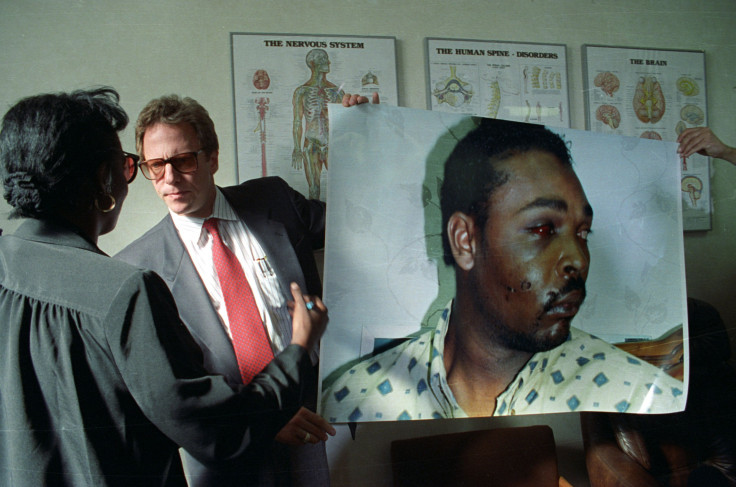

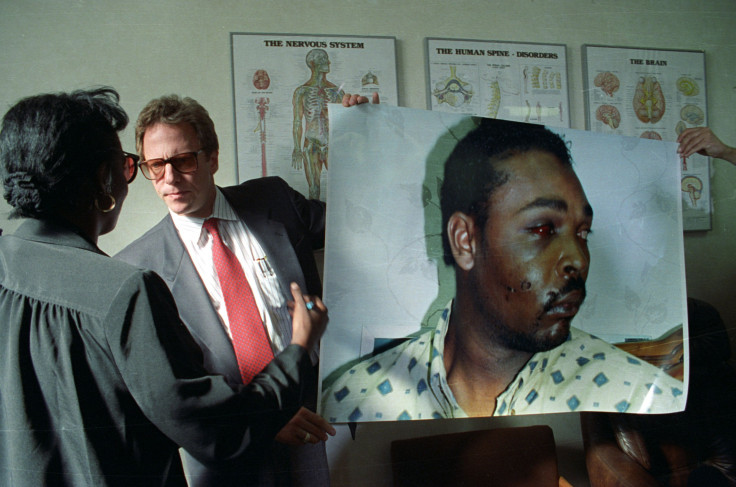

Apprehended by Los Angeles police after a high-speed chase, King was severely beaten. More than 50 blows from police batons left him with injuries including 11 fractures. George Holliday, the man who taped the scene with a camcorder in an apartment building high above, gave the video to local television station KTLA, surrendering the rights in exchange for $500.

The jarring footage ripped its way through local and national news. It appeared to show an obvious abuse of power committed by law enforcement officers against an unarmed African-American man. But after a seven-week trial, the four officers charged in the incident were acquitted of assault, sparking the Los Angeles riots that began 25 years ago today.

Video footage, then as now, does not make prosecuting a police brutality case a slam dunk. In the King case, the officers’ defense attorneys argued that the video did not show the whole picture: that King had resisted arrest and threatened the officers before Holliday began to film.

Flash forward 25 years, when citizen videos are captured not by unwieldy camcorders but by ubiquitous smartphones — and defense lawyers confronted with similarly stark visual evidence are still able to use that same tactic.

In Scott’s case, for example, the video appears to show an unarmed black man being shot by white police officer Michael Slagler after he was stopped for a tail light violation in South Carolina in 2015.

“It cannot be viewed as the same as a Saturday night killing, a typical murder case,” Slagler’s defense attorney Andy Savage told the judge. “One must look at the experience of a police officer… immediately prior to the shooting.”

The jury couldn't agree on a verdict and a mistrial was declared in December.

“If I showed you a snippet of a video, by definition, you don’t know what preceded it,” former prosecutor Cramer explained. “So it does allow a defense to say, ‘Well, ladies and gentlemen, you don’t know what preceded it, and what preceded it was important.’”

It remains notoriously difficult to convict a police officer of brutality or misconduct, with or without video. Police are not required to exhaust all of their legal alternatives before using deadly force; there is no mandatory checklist of verbal warnings, de-escalation or other non-lethal tactics. The standards merely ask if deadly force was reasonable — an extremely subjective standard, resting largely on whether the officer feared for his life or the lives of others.

“You end up with these horrific situations where it’s really hard to explain to the public that it’s legally justified but maybe not necessary, so we’re not going to charge the officer,” Phillip Stinson, an associate professor of criminal justice at Bowling Green State University who tracks fatal police shootings, told IBT.

But if visual evidence cannot reveal the mind of a police officer, it can change the national conversation. The issue of police brutality would likely get less attention — and the Black Lives Matter movement might not exist — without the proliferation of video footage.

“Historically, the police have always owned the narrative,” Stinson said. “They can write in reports whatever they want. In the Rodney King situation, I don’t think the reports were all that consistent with the video. We still see that going on.”

A multitude of forms has emerged to bear witness: dashboard cameras, body cameras, surveillance and security videos. It’s no longer unusual for a bystander to start recording as soon as an encounter with police begins.

“When I began doing police misconduct cases in 1981, people would say, ‘An officer would never do that. There’s no way they’d do that for no reason,’” Howard Friedman, a civil rights and police misconduct lawyer in Boston, told IBT. “No one makes that argument anymore. Video has made it clear that it does happen.”

Each recorded incident may find a new audience.

“We’ve seen countless videos, so many so that every person sort of has the one video that resonates with them, that activates them and convinces themselves of what’s going on,” Samuel Sinyangwe told IBT. Sinyangwe, a policy analyst and data scientist is the co-founder of Mapping Police Violence, a database of police killings.

“How do we move from a place where maybe 12 officers get indicted out of 1,200 cases to a place where each of these incidents can really be evaluated in a fair and impartial way that results in accountability?” said Sinyangwe. “That will require much further changes than just having a video. It will require the system to respond to that video in a fair and unbiased way. Video is not a solution, but it has created a space for a solution to happen. Video has helped to create a space for a conversation to be had.”

SaveSave

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.