Silicon Valley's Diversity Fail Includes White-Male Dominated VCs (And It's Killing Women And Minority Startups)

Before Karla Gallardo and Shilpa Shah began pitching venture capital firms on Cuyana, their women’s fashion brand startup that uses a unique business model to optimize margins, they figured the idea might not resonate with techie male investors. Once they got started, their suspicions were confirmed: Most of the partners they met had no idea how women liked to shop. That’s why Gallardo and Shah made a concerted effort to pitch as many VC firms with female partners as they could find.

“We focused on them because we didn't have to spend 45 minutes out of the hour explaining what a brand is and why women shop the way they shop,” said Gallardo, CEO of San Francisco's Cuyana. “They would get it right away and we could just get into the nitty-gritty of our business model.”

Despite their targeted efforts, they only met about six female partners during the process, but their plan still worked. They received $1.7 million from Canaan Partners, one of the few firms in Silicon Valley with more than one female partner.

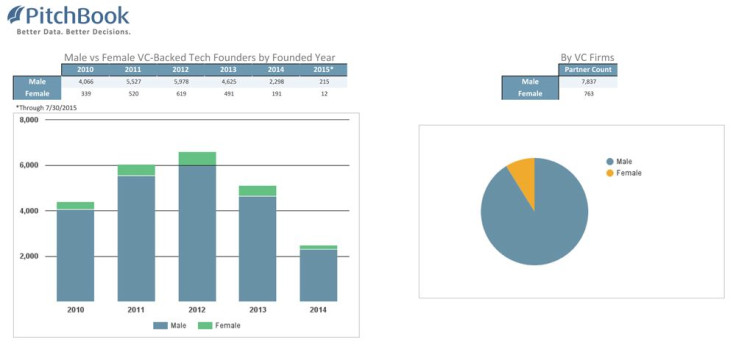

Lack of diversity within Silicon Valley is no secret, but what many in tech still don’t acknowledge is the lack of women and minorities involved in the venture capital part of the industry -- arguably the most important part. Just 9.7 percent of all partners at venture capital firms are women, and unsurprisingly, that is why just 8.3 percent of venture capital-funded U.S. tech startups founded in 2014 were led by women CEOs, according to Pitchbook. This is also why only 2 of the 84 Americans tech startups worth more than $1 billion are led by women, according to Cowboy Ventures.

“I can probably count on three fingers how many tech firms have one female general partner, and certainly more than two would be unusual,” said Maha Ibrahim, general partner at Canaan Partners.

The numbers are even more skewed when looked at by ethnicity. A 2014 list of the top tech venture capital firms shows just 1.54 percent of investors were African-American. When it comes to startups, just 1 percent of founders were black, a report by CB Insights said in 2010, the last time anyone bothered to track this data. As for Hispanic founders and partners in tech, there doesn’t seem to be much data at all. "I can't name five [Hispanic venture capital partners] -- I probably can't name three," said Manny Fernandez, CEO and co-founder of DreamFunded, a micro venture capital firm and angel investment platform.

Meritocracy Masquerade

Venture capital firms are responsible for funding the next-generation Googles and Facebooks, but women and minorities will never rise to the levels of Larry Page and Mark Zuckerberg without more support from the venture world.

“I don’t think you can really do diversity effectively in technology if you don’t look at the venture capital and entrepreneurial ecosystems,” said Lisa Lambert, managing director and vice president of Intel Capital. “They’re on the leading edge and have great power and influence in our industry.”

Though securing venture capital funding is a tough process for founders of all backgrounds, it’s especially difficult for women and minorities. For starters, partners rely heavily on their networks in deciding which meetings they take. That means that if you don’t already have a connection to the white and Asian male-dominated industry or one of the few universities that overwhelmingly feed into it, like Ivy League schools, breaking in can be tough.

“It’s a completely biased system that masquerades as a meritocracy, and by that I mean that if you’re an entrepreneur it makes a huge difference who you are and who you know as to whether you're going to get introduced to a top VC to hear your pitch,” said Freada Kapor Klein, a partner at Kapor Capital, one of the few truly diverse venture capital firms. “It isn't necessarily the best ideas or the best entrepreneurs who get funded, it’s those who most fit into the social network of the top-tier VCs.”

Even if you can get a meeting, many startup ideas from women and minorities go without funding because they solve problems that many venture capital partners don’t grok. “You may understand there’s a real problem and understand there’s a real solution, but because the venture capitalist has never seen or experienced that problem, they can’t really empathize,” said Jerry Nemorin, an African-American entrepreneur and CEO of the startup LendStreet. “They can’t understand the scale of the problem or the scale of the opportunity.”

Securing funding from venture capital firms can be a difficult process for even the most qualified of minority and women entrepreneurs. For example, KG Charles-Harris, who is African-American and the CEO of two-year-old artificial intelligence startup Quarrio, has been working in tech for decades and has assembled a team of accomplished employees, many of whom hail from MIT and Stanford and have experience working for companies like Apple and Cisco.

Over phone calls and online demos, Charles-Harris was able to raise $200,000 from foreign investors, but after numerous in-person meetings with American venture capitalists (only one of which included an African-American), he has not been able to raise a cent in Silicon Valley. “If it’s difficult for me to raise money here with that kind of background, that kind of team and that kind of product, how difficult is it for other people?” Charles-Harris said.

'Diversity Is A Competitive Advantage'

Consumer-facing tech companies like Apple and Dropbox have been forced by public pressure to reevaluate their hiring and make efforts to be more inclusive, but because the funding aspect of the tech industry is so far removed from the public eye, venture capital firms have not faced that same pressure. The industry caught shards of it following the Ellen Pao sexual harassment case earlier this year, but otherwise, VC firms get a free pass.

“Many people across the United States and the world know what Facebook, Google and Twitter are, but not many people are going to know what Venrock, Benchmark, Sequoia or Andreessen Horowitz are,” said Richard Kerby, vice president at Venrock. “There’s less of a microscope on us, and therefore the conversation is less steered toward us.”

Many top venture capital firms in tech, including Andreessen Horowitz, Greylock Partners, Benchmark Capital, Accel Partners, Sequoia Capital, and Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield and Byers, either did not respond to interview requests or declined to comment.

To be sure, there are signs that change is afoot, albeit slowly. Recently, the National Venture Capital Association, Dow Jones VentureSource and CrunchBase launched the 2015 Venture Census, a voluntary survey to get fresh data on the gender and demographic breakdown of the venture industry.

More importantly, a handful of firms and companies are launching initiatives that focus exclusively on funding companies led by women or minorities. Micro firm DreamFunded announced a $1 million diversity-focused fund last week, while Intel Capital, a division of Intel Corp., did the same in June with a $125 million fund. AOL started the women-focused BBG Fund in 2014 while Comcast Ventures trailblazed the way in 2011 with the $20 million Catalyst Fund, which focuses on providing seed money to minority entrepreneurs.

“When you look at the folks who are starting these companies that we focus on, typically they don’t have the same networks that are available to other entrepreneurs, and the hardest part is getting that initial amount of funding to really get the company going,” said Lo Toney, a partner at Comcast Venture’s Catalyst Fund.

For the truly opportunity-driven venture capital firms, though, it is in their best interest to bring on more diverse partners and invest in more women and minority founders. Women make up half the population, while white people are expected to lose their majority status around the year 2040. If venture capitalists continue to ignore the ideas of women and minorities, they’ll be leaving millions, if not billions, on the table.

“If venture looked like America then the businesses created would have the potential to be huge businesses that serve all of America,” said Klein, whose team of five at Kapor Capital includes two women and three persons of color. “That puts us in an almost unique category among venture capital firms, and it was very intentional. We believe that diversity is a competitive advantage.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.