Skillful Human Hands Evolved Even Before The Ability To Walk: Study

Early humans started using their hands to manage various tools even before they learned how to walk, according to a new study by the RIKEN Brain Science Institute, or RIKEN-BSI, in Tokyo.

The study combined behaviors of monkeys and humans, and examined images of their brains and fossil evidence to overturn a widespread theory which suggests that the development of bipedal locomotion preceded the evolution of manual dexterity to free human hands to use fingers to control various tools.

“Evolution is not usually thought of as being accessible to study in the laboratory,” Atsushi Iriki, the study's leader and a neurobiologist at RIKEN-BSI, said in a statement. “But our new method of using comparative brain physiology to decipher ancestral traces of adaptation may allow us to re-examine Darwin’s theories."

According to the study, published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B on Monday, the researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, in humans to measure brain activity by detecting associated changes in blood flow. In addition to the fMRI test, the researchers also employed electrical recording from monkeys to locate areas in the brain that are responsible for sensing touch in individual fingers and toes.

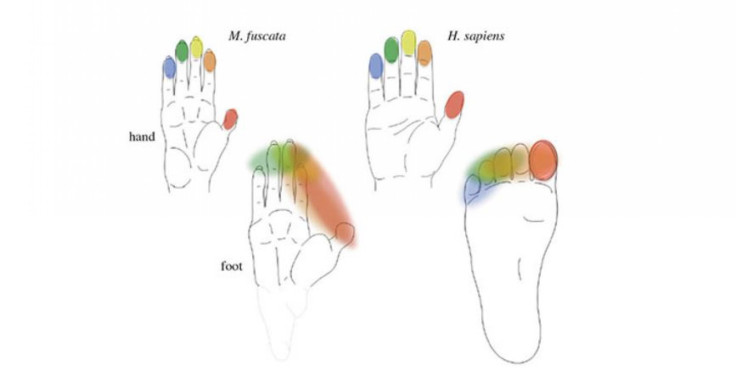

Based on the results of these tests, the researchers confirmed earlier studies, which showed that single digits in the hand and foot have separate neural locations in both humans and monkeys.

The results even showed new evidence that toes in both monkeys and humans can be combined into a single map. But, while human toes can also be fused into a single map, a prominent exception is the big toe, which has its own map not seen in monkeys.

The findings helped the researchers suggest that pre-historic humans developed dexterous fingers when they were still quadrupeds. While manual dexterity did not expand further in monkeys, humans gained fine finger control and a big toe to help them walk.

The study was supported by the examination of well-preserved bones from the hands and feet of a 4.4 million year-old skeleton of the quadruped hominid Ardipithecus ramidus, which is a species with hand dexterity that existed before the human-monkey lineage split.

“In early quadruped hominids, finger control and tool use were feasible, while an independent adaptation involving the use of the big toe for functions like balance and walking occurred with bipedality,” the study said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.