Some EU Countries Are Building Fences, Walls To Keep Migrants Out

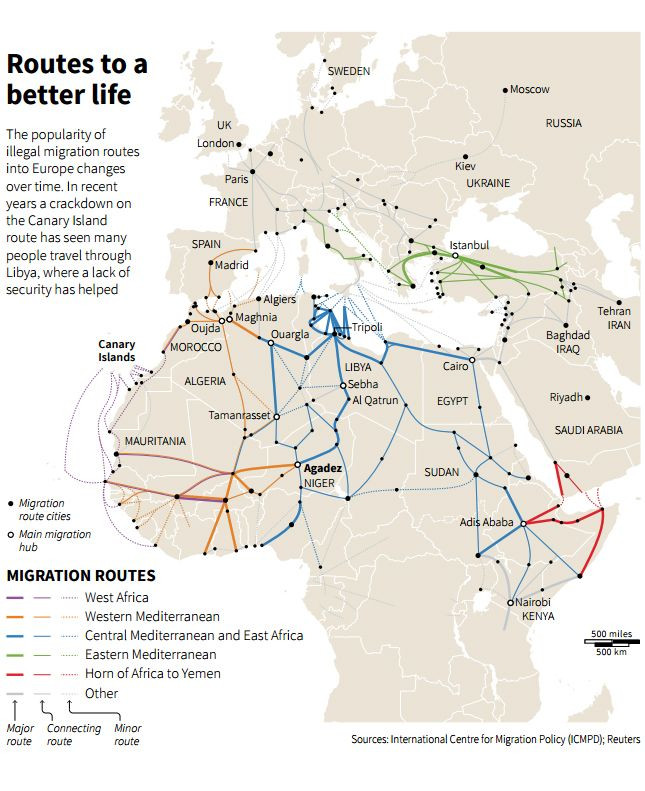

More than 100,000 undocumented migrants have landed on the shores of southern Europe this year, most of them on smuggling boats from Libya, a number likely to increase drastically this summer, the U.N. says. The massive influx is overwhelming not only humanitarian organizations scrambling to provide services but also European governments trying to find ways to balance helping the migrants, who are often refugees fleeing war, with managing domestic concerns about their arrival.

To stem the flow of migrants, the European Union launched Monday a naval operation to disrupt the trafficking and smuggling networks that are bringing people across the Mediterranean Sea from North Africa. The operation is billed as a way to save more people from death. Every year, thousands die as rickety boats sink or capsize, overwhelming the current ability of rescuers to get to everybody on time.

“A tragedy of epic proportions is unfolding in the Mediterranean,” the United Nations and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) said in a joint statement in April. “We ... strongly urge European leaders to put human life, rights, and dignity first today when agreeing upon a common response to the humanitarian crisis."

The naval operation, though experts say it is a step forward in solving some of the issues in the migrant crisis, will not solve the crisis. And it does not address the concerns of some European countries that say there are other migrants, those who have already landed on the Continent and those coming in via land from the east from countries like Iraq and Syria, who are adding to their overwhelmed immigration systems.

Faced with bleak economic forecasts and rising unemployment, several European countries are instituting new measures to keep migrants out. Hungary and Bulgaria are building walls, literal fences, on their southern borders that have as much to do with appeasing electorates wary of new immigration as with actually keeping people out.

In Europe, where the remnants of the Berlin Wall still scar the capital of the Continent’s richest country, that may stir uneasy memories of the recent past. But the electoral success in the 2014 European Parliament elections of xenophobic, right-wing parties in many EU countries shows that immigrant-bashing rhetoric is finding favor with voters.

Hungary has announced plans to build a wall along its 109-mile (170-kilometer) border with Serbia, where the majority of migrants enter the country. According to U.N. estimates, there was a sharp rise in the number of migrants and asylum seekers entering Hungary in 2015. Government figures show that more than 54,000 migrants have entered the country so far this year, about 10,000 more than in all of 2014.

Meanwhile in Bulgaria, the government is building a 100-mile fence on its border with Turkey, one of the key smuggling points for the Islamic State group, which operates in Iraq and Syria, both sharing a border with Turkey. Bulgaria, the poorest country in the European Union, finished building a 20-mile section of the fence in September.

Just like Hungary, Bulgaria is a member of the EU, while Serbia and Turkey are not. Building walls between two member countries of the EU, where travel is liberalized and people do not need passports to cross national borders, would be a nonstarter even for the most rabid xenophobes.

The construction of the new walls and fences will force migrants to adjust their travel and will shake up the decade-old smuggling networks. But the new barriers will not “necessarily deter flows of immigrants,” said Elizabeth Collett, director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe, a research group based in Brussels focusing on international migration. “Some will divert to an alternative route, and others will find ways to circumvent the wall more directly.”

Migrants can get through parts of the wall that Greece set up on its border with Turkey, Collett said, because the cash-strapped government has not invested in maintaining it. It is falling down and crumbling in some places, she said.

And since fences and walls will not stop the flow of migrants but rather divert it, the barriers are “conceived to please public opinion,” said Marc Pierini, the former EU ambassador to Turkey as well as to Syria and an expert at the European Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think tank based in Brussels.

According to a study released in January by the IOM, out of all the regions in the world, people in Europe are the most negative on immigration. Residents in the Mediterranean area, the biggest entry point for migrants from North Africa and the Middle East, would like to see immigration levels decreased. Greeks, with 84 percent, show the highest percentage in the world of people who want immigration levels decreased.

Negative views about immigration "are a political tool for right-wing parties,” Pierini said of Bulgaria and Hungary, which both have conservative parties in power.

As for Serbia and Turkey, the countries on the other side of those walls on the border of the EU, they too are making it difficult for people to enter the country, Collett said.

Serbia, for example, is slowing down processing of asylum requests, while calling on other countries in the region to take on more of the burden. Turkey continues to close down its borders with Syria periodically, forcing people fleeing the war to either risk an illegal crossing or stay in a country where four years of conflict have killed so far more than 200,000 people.

“It really is a mess,” Pierini said. “It is a problem of tolerance and management, and there is no quick fix.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.