Spectacular View Of Colliding Galaxies Provides Glimpse Of Early Universe

Astronomers, using telescopes on the ground and in space, as well as the gravity of distant galaxies, have obtained what they claim to be the best view yet of an ongoing collision between two galaxies. The findings also provide a glimpse of what the universe might have looked like when it was half its current age.

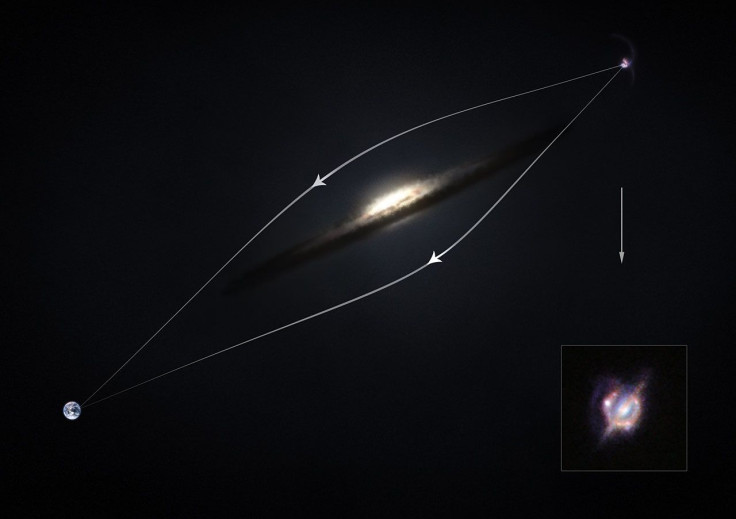

With the help of a phenomenon called gravitational lensing, astronomers captured the image of a distant galaxy called “H-ATLAS J142935.3-002836,” which is so distant that its light was originally emitted when the universe was only half its current age. According to scientists, the universe is approximately 13.8 billion years old.

“While astronomers are often limited by the power of their telescopes, in some cases our ability to see detail is hugely boosted by natural lenses, created by the Universe,” Hugo Messias of the Universidad de Concepción in Chile and the study’s lead author, said in a statement. “Einstein predicted in his theory of general relativity that, given enough mass, light does not travel in a straight line but will be bent in a similar way to light refracted by a normal lens.”

Cosmic lenses are created when multiple galaxies are precisely aligned, deflecting the light from objects behind them due to their strong gravity. This effect, called gravitational lensing, helps astronomers study objects, which would not otherwise be visible, in greater detail. Gravitational lensing also allows astronomers to compare local galaxies with more remote ones and view them as they would have appeared when the universe was significantly younger.

“These chance alignments are quite rare and tend to be hard to identify… but, recent studies have shown that by observing at far-infrared and millimetre wavelengths we can find these cases much more efficiently,” Messias said.

In order to get as much data as possible, the astronomers used several telescopes including the Hubble Space Telescope and Spitzer in space, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile, the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and the Karl Jansky Very Large Array in Mexico. Further analysis of the data obtained from these telescopes revealed that two disc-shaped galaxies were colliding with each other while creating hundreds of new stars in the process.

“With the combined power of Hubble and these other telescopes we have been able to locate this very fortunate alignment, take advantage of the foreground galaxy's lensing effects and characterize the properties of this distant merger and the extreme starburst within it,” Rob Ivison of the European Southern Observatory and the study’s co-author, said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.