Superbugs Could Kill 10 Million People Annually, Cost $100 Trillion By 2050: Report

That antibiotic you just popped, what if it made the germ stronger instead of curing you?

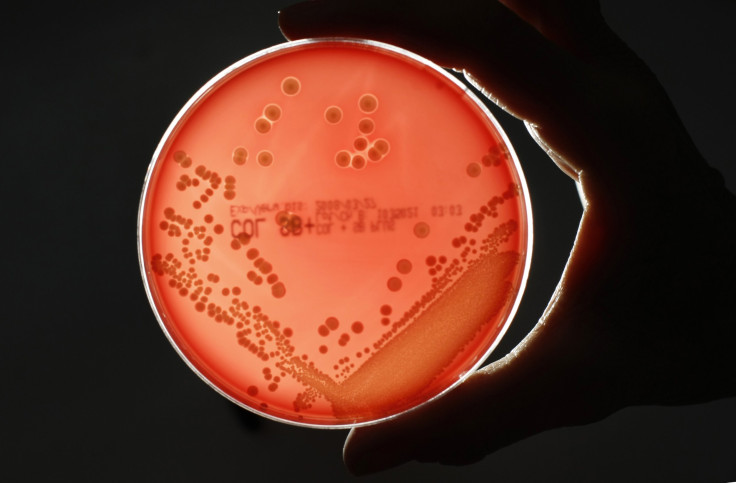

As infection-causing microbes evolve and grow resistant to subscription medicines, the number of superbugs continues to grow. Till a few decades ago, they were mostly confined to hospitals and other medical establishments, but are becoming increasingly commonplace and have been linked to various epidemics over the last few years. And if something isn’t done about this soon, things are about to get a whole lot worse.

Or, at least, so says a reputable report, the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, which was commissioned by the United Kingdom government “to analyze this global problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and propose concrete actions to tackle it internationally.” Compiled by economist Jim O’Neill, the report outlines “a world in 2050 where AMR is the devastating problem it threatens to become unless we find solutions.”

About 700,000 people die every year already, the report said, but grimly warned the figure would go up manifold to 10 million AMR-related deaths every year, or one person every three seconds, surpassing the number of those that die of cancer currently.

“Even at current rates, it is fair to assume that over one million people will have died from AMR since I started this review in the summer of 2014,” O’Neill said in the report.

Being an economist, his report also put an economic cost to the increasing problem of AMR. Based on detailed scenario analyses carried out by consultancies KPMG and Rand, the report said “the cost in terms of lost global production between now and 2050 would be an enormous $100 trillion if we do not take action.”

After pointing out the problems, the report also makes suggestions for ways to tackle the looming menace.

The first suggestion is for “a global public awareness campaign to educate all of us about the problem of drug resistance,” and the report calls for it to be supported by the United Nations at its general assembly meeting in September.

Another intervention would be “to tackle the supply problem,” because “we have not seen a truly new class of antibiotics for decades.” The report recommends “market entry rewards” for developers of new antibiotics, subject to certain conditions.

The third suggestion in the report is to reduce the use of antibiotics among both humans and animals, since their “unnecessary use … speeds up drug resistance.” This would require an overhaul of the current diagnostic tests used by doctors.

Another important recommendation of the report is to “reduce the extensive and unnecessary use of antibiotics in agriculture.” It advocates the “need to make much faster progress on banning or restricting the use in animals of antibiotics that are vital for human health.”

Implementing the suggestions made in the report has its own costs, and there are further suggestions in it, such as a levy on the pharmaceutical sector, to raise the money needed. The report makes a dark forecast but says the challenge is one “well within our ability to tackle effectively.”

Reacting to the review, Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization, said it “takes forward many issues raised in the WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Importantly, the review tackles the burning need to find incentives that can get new products into the pipeline. If not, the scenario it paints for 2050 will surely jolt the last remaining skeptics into action.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.