Syria Peace Talks Hinge On Which Factions Are Considered Terrorist Groups

BEIRUT— It started with an Arab Spring and ended in perpetual winter: Five years after the first uprising in Syria, the country is entrenched in a brutal war that has become a battleground for regional and global combatants. What started as a series of protests by Syrian nationals calling for free and fair elections now encompasses the world’s superpowers and the most dangerous terror groups, making the prospect of finding a peaceful solution to end the violence as complex as the conflict itself.

A six-month-long U.N. peace negotiation in Geneva, informally known as Geneva III, was set to begin Friday, but it was not clear that western-backed rebels would participate.

The talks aim to end a war that has resulted in the deaths of more than 260,000 people and displaced millions. With so many different factions fighting on the ground — including both state and non-state actors — even the list of invitees for negotiations is a point of contention, with each prism in the kaleidoscope of the Syrian battlefield reflecting its own idea of what a successful solution should be.

“The talks may provide some symbolic purpose in showing a small measure of agreement on the need to end the fighting, [but] they are more likely to illustrate how distant peace remains,” according to a report from Soufan Group, an intelligence and risk consultancy.

The ultimate purpose of the talks is to broker a political solution that will eventually lead to a democratic election. But the first priority is to impose a national cease-fire that would put an end to the violence.

In past negotiations, the United States has said that the departure of President Bashar Assad should be the primary goal of any political solution. More recently, that aim has been quashed by the Syrian regime’s refusal — with the backing of its allies Russia and Iran — to participate in talks. Since a political solution is impossible without Assad’s cooperation, that demand has subsequently been dropped. “The winner in all this is inarguably Assad,” the Soufan Group reported. “He has already seen off an attempt by the U.S. to make his departure the starting point of a transitional process.”

The Syrian Regime

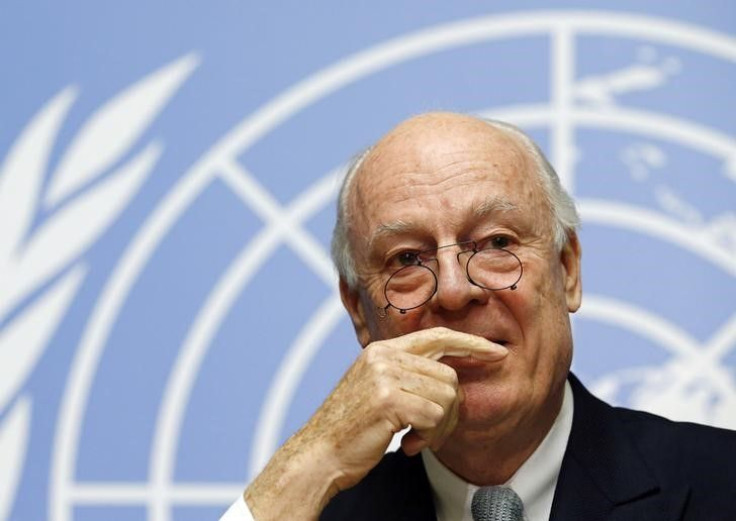

The United Nations Special Envoy Staffan de Mistura sent out invitations for the peace talks earlier this week, with 15 delegates a piece from the pro-Syrian regime side and the opposition side. On the pro-regime side, a delegation from the Syrian government was invited along with representatives from Russia and Iran.

The invitations to the opposition proved more problematic. While it was widely agreed that terrorist groups should not be included at the negotiating table, the participating world powers disagreed on the classification of the various rebel groups. The Jordanian delegate was assigned the task of determining which groups are terrorists but since the categories are subjective they are unlikely to be accepted by everyone.

Opposition Factions

The Islamic State group and Jabhat al-Nusra, Syria’s branch of al Qaeda — both designated as terrorist organizations under international law — were not invited to participate, despite both occupying large swaths of Syria.

Representatives from the Saudi Arabia-backed opposition coalition, the High Negotiations Committee, were invited to the talks. Syrian army defector Asaad al-Zoubi is the leader of the coalition that includes Mohammad Alloush, the delegate for the prominent opposition faction Jaish al-Islam, also known as the Army of Islam, which is considered a terrorist group by the Syrian regime and its Russian allies.

The Committee announced Thursday it would not attend negotiations if their requirements were not met: They demanded that food and medical aid be provided to the roughly 400,000 starving people in besieged areas, nearly half of whom are residents of towns surrounded by regime and allied forces.

#Syria's opposition holding its ground: will "certainly" not be in Geneva tomorrow, Assad's airstrikes and starvation-sieges haven't stopped

— Kyle W. Orton (@KyleWOrton) January 28, 2016Riad Hijab, coordinator of the High Negotiations Committee, told Al-Arabiya television Thursday: "Tomorrow we won't be in Geneva. We could go there, but we will not enter the negotiating room if our demands aren't met.”

The coalition said it would attend the negotiations if their demands were met "within two, three or four days."

Late Thursday evening, the U.S. urged the coalition to attend the meeting and stressed the importance of the negotiations.

"This is really an historic opportunity for [the committee] to go to Geneva to propose serious, practical ways to implement a ceasefire and other confidence-building measures," State Department spokesman Mark Toner said. "We believe these demands, while legitimate, shouldn't keep the talks from moving forward."

The Kurdish Question

The Kurdish factions in Syria are another point of contention for the Committee — the inclusion of the Kurds, who have very active fighting forces in Syria, have become the wildcard for both sides in the war.

The armed faction of the Syrian Kurdish group Democratic Union Party (PYD) has been a major player in the fight against ISIS and a reliable U.S. ally on the ground. However, Turkey, another U.S. ally in the war on ISIS and a NATO member, considers the faction to be a terrorist group. In the week leading up to the talks, Turkey said it would boycott negotiations if De Mistura invited a representative from the PYD, which is aligned with the Turkish Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist group and a long-standing enemy of the Turkish government.

Today's most popular item in Kurdish social media world showing discontent over Geneva #YPG #YPJ pic.twitter.com/yTj3M57Y1z

— Mutlu Civiroglu (@mutludc) January 29, 2016"In which capacity would the PYD sit at the table?" Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu asked in a live interview on the NTV television. "There cannot be PYD elements in the negotiating team. There cannot be terrorist organizations. Turkey has a clear stance."

The allegiances of the Kurds in Syria have fluctuated over the past five years. The Kurdish factions have made it clear that if they did not receive support from the international community they would accept backing from elsewhere, including the Syrian regime.

The rebel coalition has potentially created a loophole for Kurds to be included in the talks, which could draw the powerful fighting force of the Kurdish militias to their side, but only without their political wing. Earlier this week, Fuad Aliko, a member of High Negotiations Committee and political representative for the Syrian National Coalition, the opposition’s main political wing, said the Kurdish people and the militias are “a key component of the Syrian opposition [with] representatives in the opposition’s negotiating delegation.”

For a political solution to be successful and for a national ceasefire to be respected in Syria, the agreement must be inclusive of the major fighting factions in Syria. But this round of peace talks, like the ones that have come before, is still stuck on the guest list.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.