Syrians Say Fear Was Major Motivation For Voting In Election Assad Was Certain To Win

DAMASCUS, Syria --The few voters who trickled into a polling station in central Damascus chatted about the blue ink in which they were required to dip their finger prior to voting, and the needles that the polling station was rumored to have in case one wanted to prick their finger and vote with blood.

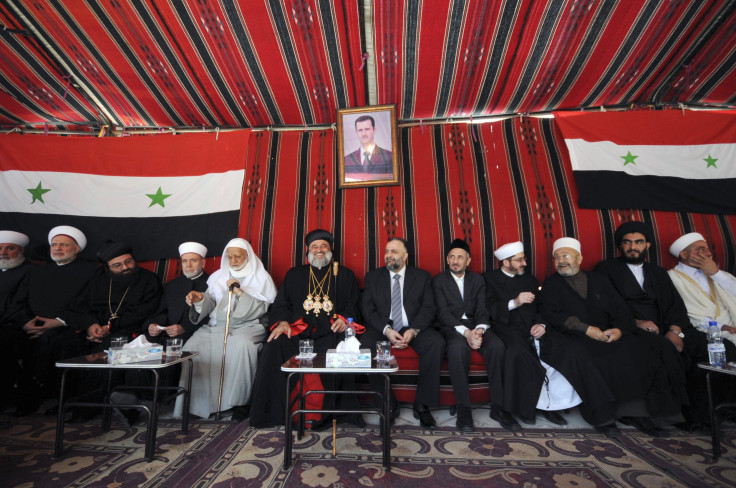

On the ballots were color head shots of the three candidates -- President Bashar al-Assad and two also-rans, businessman Hassan al-Nouri and lawmaker Maher Hajjar.

There were no obvious irregularities or violations of voting protocol reported at polling stations throughout Damascus, butmany Syrians said they voted only due to rumors that they might be penalized if they abstained, and some thought the blue ink would be a first indicator.

“If I don’t have ink on my finger, will they harass me at checkpoints today and tomorrow?” one Damascene who abstained from voting asked, adding that he planned to stay home all day “just in case.”

Leila, a 47-year-old mother of four, also considered abstaining from participating in what she called a sham election, but changed her mind. “I’m totally anti-government, but today I will vote for security reasons, because I live in this country and I have children and I don’t want to be earmarked as a nonvoter,” she said. “God knows what consequences that could bring onto my family.”

Many Syrians expected nonvoters to be flagged and subject to arrest and harassment. In government-controlled areas including the capital, Homs and along the Syrian coast, some wondered if they could get away with casting a blank ballot, though those who opposed the government said they feared authorities would track them down if they abstained. No one expected even a high voter turnout to have any impact on the outcome. Al-Assad was predicted to win by a huge landslide. Even among Syrian refugees who voted at the Syrian embassy in Lebanon or crossed the border to vote in Syria, then returned to Lebanon, most who spoke with International Business Times said they were doing so because they feared the authorities would otherwise deny them entry back to their embattled towns.

The government has done little or nothing to dispel such rumors, which have persisted throughout election day.

When the polls opened, Damascenes were rudely awakened by low-flying warplanes that created unprecedented sonic booms that frightened many out of bed, apparently part of the government’s tighter-than-usual security measures on election day.

“It was the sound of death coming at me, I was convinced of it,” said Ghada, a resident in her fifties in the affluent neighborhood of Abu Roumaneh. She added that she initially thought it was a rocket coming toward her. “We’ve had mortars and rockets come at us many times in the past months, so I know the sound very well. But this? It was a hundred times louder and more determined. I’m still shaking.”

Another resident in the middle class neighborhood of Baramkeh in east Damascus said: “I was by the window, and the few people downstairs in front of the bakery started running like crazy. People in my building came out of their homes and some of my neighbors started running downstairs to the basement before we realized it wasn’t a rocket, but a warplane,” said a man in his thirties.

The maneuvers were part of a wide array of security measures most believed were intended to thwart rebel attacks on Damascus on election day, which both residents and the authorities have been anticipating.

“Our warplanes are protecting the city today,” said one military official on condition of anonymity. “They’re purposely flying low to keep close watch on the ground and make sure [the rebels] don’t fire mortars and rockets at us."

The potential for car bomb and suicide attacks brought parts of the city to a standstill, with commuters prevented from entering from the suburbs except for public sector employees on their way to work. Others in Damascus have complained that the Internet has been unusually slow or non-functioning for the past 72 hours, which some attribute to government intrusion. In the streets of Damascus, traffic was relatively light and most cars had uniformed and armed government security inside or sitting on the roofs to keep watch. Some cars blared pro-Assad music.

The specter of warplanes buzzing the skies of Damascus is not unusual -- it’s been happening for two years as the planes make their way to bomb rebellious suburbs. But the droning sound of warplanes high in the sky followed by the muffled blast of it bombing the suburbs, which continued on election day, paled in comparison with the show of force that included the shocking sonic booms. The fighter jets flew so low and slow over the city that many residents were able to photograph them or try to decipher the type of plane.

“It must be a Sukhoi, because MiG warplanes don’t make this tailing sonic sound,” said one resident in Mazzeh.

The debate continued on social media, with eye witnesses claiming they could tell the make of the jet because it was so low and close.

For days, online activists had solicited information about the movement of security personnel around Damascus in hopes of figuring out where and when Assad would vote.

Government shelling of rebellious pockets around Damascus continued as it has for months, though on election day many believed the attacks were louder and more intense – which may have been a result of the city's otherwise remarkable quiet.

Toward the end of the day, authorities had hastily removed the ubiquitous campaign billboards, which were a particular source of consternation among anti-government residents due to the perceived expense behind them. “With all that money they spent, they could have instead spent it to help displaced Syrians, or to rebuild schools,” said one Damascene. “And all this money on the warplanes and the fuel for them flying. It could have gone to better use.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.