Tunisia’s $1 Billion Smuggling Problem

Smuggling Is On The Rise In Tunisia – But What Are The Benefits?

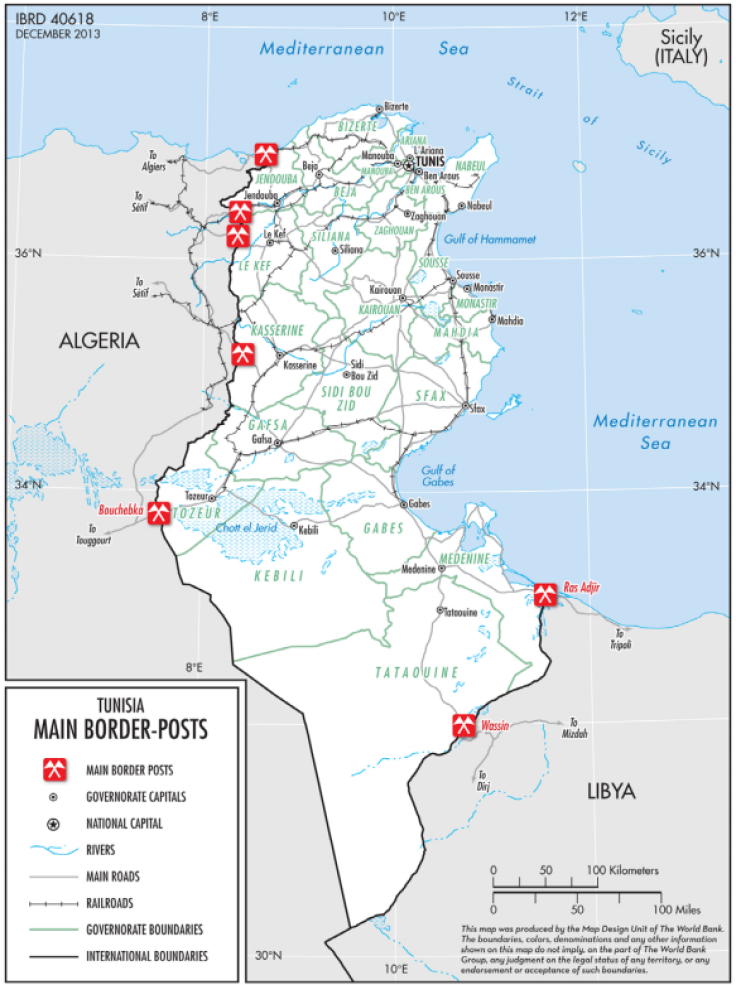

The Tunisian government is losing a major chunk of public revenues due to “informal trade,” or smuggling, over the Libyan and Algerian borders. The World Bank estimates that this illegal transport of goods is worth more than $1 billion to Tunisia -- after it analyzed official data and conducted surveys at border areas.

It accounts for nearly half the country’s trade with Libya, and a significant amount of Algerian trade.

According to a recent report, informal trade has “developed significantly in the last few years of the previous political regime,” and “it appears to be following the revolutions in Tunisia and Libya.”

After the Tunisian and Libyan revolutions, a prominent border facility was attacked and vandalized. “Following a number of other problems and the closing of the border on two separate occasions, customs authorities were unable to properly control cross-border trade flows,” the report read.

Currently, many different groups are involved in smuggling in different ways, according to the report.

“While some are highly visible, such as transporters carrying the goods across the border, street vendors, and ad hoc traders (known informally as 'ants') and others are less so, such as wholesalers, currency changers, and officials in the relevant administration who are willing to turn a blind eye on the practice,” according to the report.

But most smugglers aren’t criminals -- they’re economic opportunists, according to some.

According to Gael Raballand, a World Bank senior public sector specialist, informal trade fills certain market gaps, as he wrote in a Tuesday blog post.

For example, diesel fuel costs about $0.82 per liter in Tunisia but just $0.13 in Libya and $0.19 in Algeria.

Plus, the Tunisian government charges duties from 20 to 40 percent on various articles -- the duty on tires is 27 percent, and it's 36 percent on apples. But for a small payment of roughly $30 to a border guard, cars filled with material can pass through.

“If fuel and other goods can be smuggled across the border with relative impunity, the economic incentive is enough to lure Tunisians -- many of whom are already struggling to find sources of income -- into informal jobs as wholesalers, transporters and various service providers,” Raballand wrote.

In one border town examined by the World Bank, more than 20 percent of the population is considered to be working in informal trade -- which makes it the region’s most important economic sector.

Raballand said that a government crackdown could only lead to further unrest or violence. And the informal sector is sustaining many areas that have not yet developed into mature industries.

“Smuggling is a family business that began a long time ago,” Riyadh, a man who transports contraband goods back and forth between Tunisia and Algeria, told the Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

“There are very few job opportunities, and only a few people from my region finish university," he said. "This is our only way of providing a sustainable life."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.