US And China Conflict Latest News: Beijing Seizes American Underwater Drone

In an unprecedented move, China’s navy captured an American drone cruising beneath the surface of the South China Sea, prompting U.S. officials to demand its return Friday, Reuters reported.

The Chinese warship grabbed the unmanned underwater vehicle, or UUV, Thursday just north of the Philippines, around the time the USNS Bowditch, an American oceanographic surveying vessel, had planned to pick it up, an anonymous defense official told the newswire.

“The UUV was lawfully conducting a military survey in the waters of the South China Sea,” the official told Reuters. “It’s a sovereign immune vessel, clearly marked in English not to be removed from the water, that it was U.S. property.”

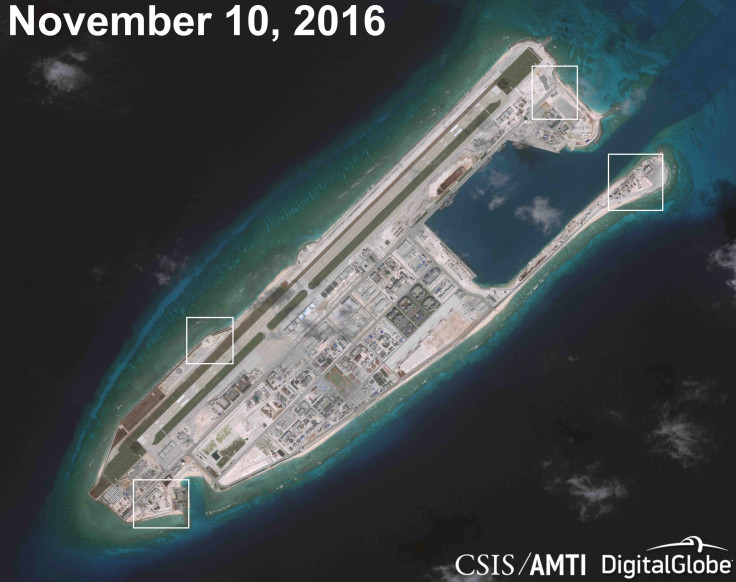

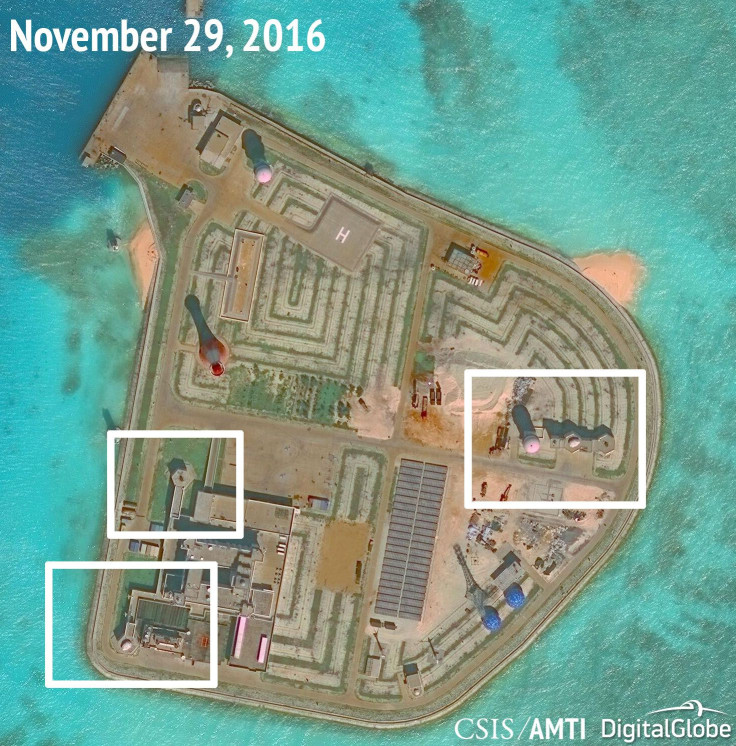

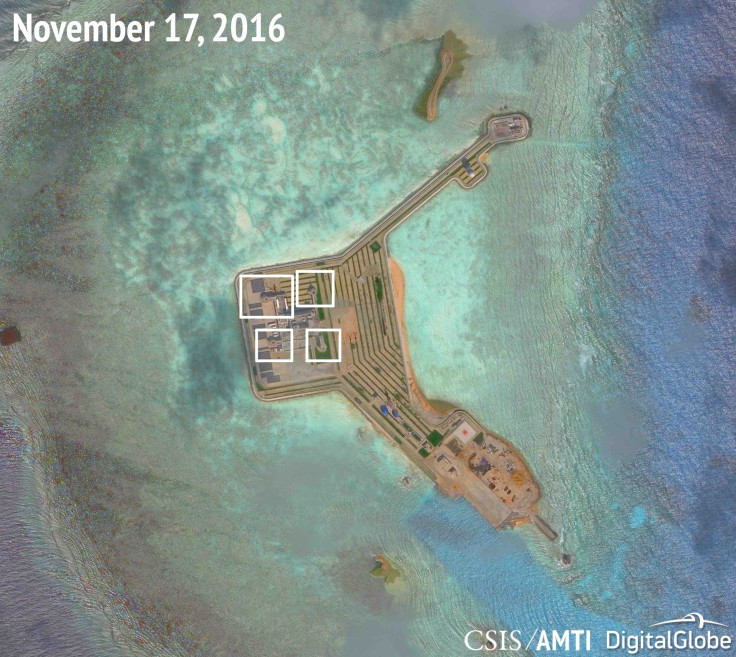

The seizure followed news just three days earlier that Beijing had constructed large defense systems on the South China Sea’s disputed Spratly Islands, which not only China but Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan, Vietnam and the Philippines claim to own. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, a branch of the Center for Strategic and International Studies that began tracking China’s island buildup over the summer, published seven photos, dated between Nov. 10 and Nov. 29, showing a variety of hexagon-shaped structures, evidence of “buried chambers” and platforms “consistent with the pattern of larger anti-aircraft guns.”

Essentially confirming the group’s suspicions, the Chinese defense ministry issued a statement Thursday announcing that it had placed on the islands a variety of weapons it planned to use to “slingshot” external threats, the New York Times reported.

Back in May 2015, U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter urged China to end construction and militarization of islands in the South China Sea, calling such actions “out of step” with multilateral efforts to maintain peace in the region. Speaking at a ceremony at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, Carter also signaled to China’s less-powerful rivals that the U.S. would remain a significant military counterweight in the South China Sea.

“China’s actions are bringing countries in the region together in new ways,” he said, according to Reuters. “They’re increasing demand for American engagement in the Asia Pacific. We’re going to meet it.”

Carter added that the U.S. “will remain the principal security power in the Asia-Pacific for decades to come.”

Beijing responded to the criticism by accusing the U.S. of holding “double standards,” with a foreign ministry spokeswoman noting that American officials “have been selectively mute” in cases of other Asian nations infringing on China’s territories.

“The Chinese people can make their own judgment,” the spokeswoman said, according to the newswire. “No one has the right to tell China what to do.”

Since then, tensions between Washington and Beijing have loosened, with several exceptions. On May 11, for example, the guided missile destroyer USS William P. Lawrence headed within a 12-mile radius of Chinese-claimed Fiery Cross Reef, leading Beijing to send two fighter jets and three warships after the U.S. vessel in an attempt to push it out of sovereign Chinese waters.

Less than a week later, Chinese military plane intercepted a patrolling U.S. reconnaissance aircraft, within of which the Chinese jet flew just 50 feet. While the Pentagon characterized the maneuver as “unsafe,” China’s defense ministry told Reuters the U.S. was “deliberately hyping up the issue of the close surveillance of China by U.S. military aircraft.”

Days later, the newswire reported, a Chinese defense spokesman demanded an end to U.S. surveillance in and around China, arguing that such patrols were “seriously endangering Chinese maritime security.”

And relations may further sour, as the U.S. just elected Donald Trump, who campaigned on an aggressive stance toward China as well as a large military buildup — including the construction of 350 new Navy ships.

Six weeks before the president-elect was set to enter office, he's already sparked diplomatic friction when he took a planned telephone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, shattering decades of foreign-relations protocol in which Washington has quietly aligned with Beijing’s “One China” policy, recognizing Taiwan as a territory of China rather than a sovereign state. Beijing placed the blame on Taipei rather than Washington, calling the move “petty.”

Trump tried to play off the incident as a spontaneous congratulatory call.

But the Taiwan newspaper that broke the story said otherwise.

“Trump reportedly agreed to the call, which was arranged by Taiwan-friendly members of his campaign staff after his aides briefed him on issues regarding Taiwan,” the Taipei Times reported, citing sources in Washington.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.