Vietnam Veterans: Taking The Mantle As America’s Oldest Soldiers

Vietnam veterans were the last generation of soldiers drafted and the first to be spat on. Now, as they enter their upper years, the Veterans Memorial is what binds them together.

WASHINGTON — Michael Mc Mahon, a tall, graying man in his 70s, speaks with a distant trace of his hometown accent forged in Park Slope section of Brooklyn, New York. When he was 18, the Army drafted him, scooped him up from home and plopped him into the 9th Infantry Division. Almost 50 years later, Vietnam is still in his life.

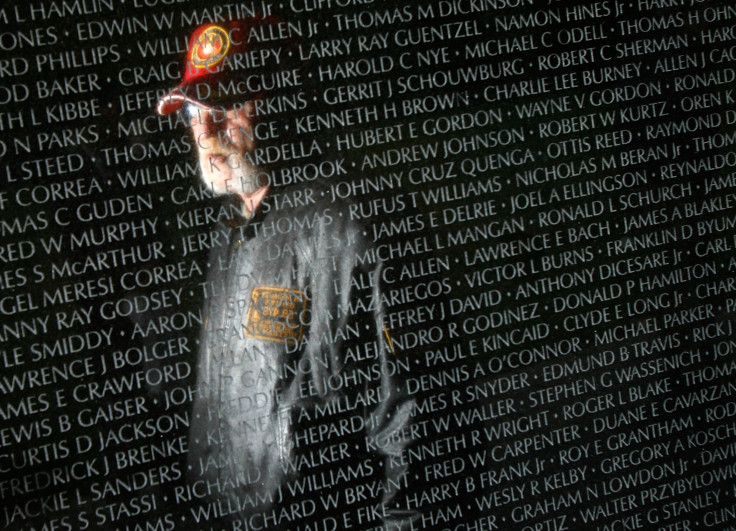

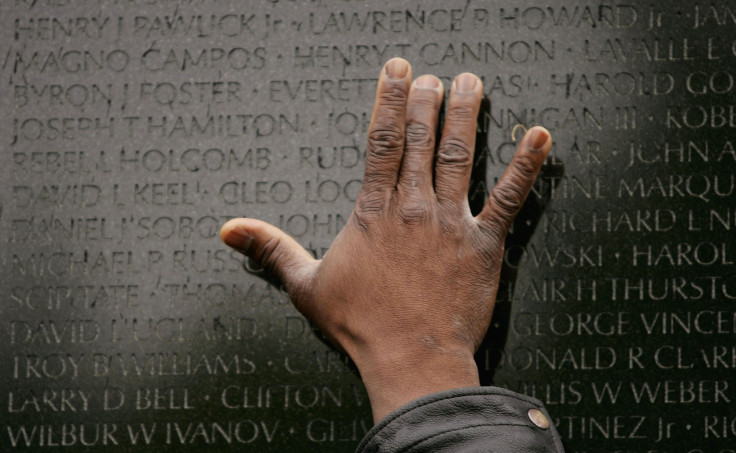

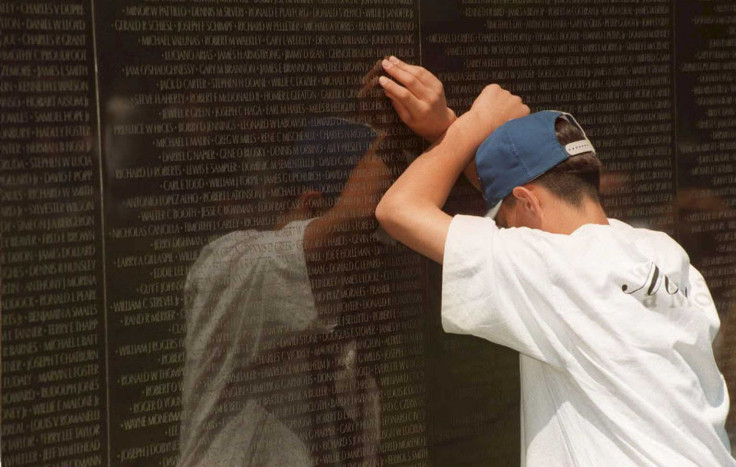

On a brisk December day he stood sentry at Constitution Gardens in Washington in front of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the iconic wall displaying thousands of names of the deceased across massive sheets of black granite. Unlike at other monuments, visitors are encouraged to walk up, to touch it, to run their fingers across the names of the dead engraved into the rock face.

“It changed the way of mourning,” Mc Mahon said.

Most national parks are more structured in their volunteer programs, but the Vietnam memorial has a much more informal system of coverage. There’s not a controlled entrance, so volunteers can come in at any time of day or night. There are no doors, but there are rules. The volunteers’ job is to enforce them.

“You get a lot of veterans here, and it’s very emotional for them,” said Henry Lazzaro, a bald, gruff volunteer and former captain in the Navy. He started volunteering last summer and comes down most Thursdays. “They’re remembering their friends who died, their sons and brothers. A party atmosphere would not be conducive to the scene.”

That’s an understatement. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial enjoys a distinctly different vibe than, say, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York. There you can see selfie sticks, tourists snapping photos, sometimes even children playing around visitors’ ankles.

“That’s one of the things we try and do, keeping people from jogging or riding bikes or walking dogs,” Lazzaro said briskly. “Keepin' ’em off the grass. Kids wanna go on the grass.”

The Americans who served in Vietnam were the last generation of soldiers to be drafted and the first generation not to be celebrated upon their return. Their war memorial, designed by Chinese-American Maya Lin in 1981, weathered a period of intense political backlash within and outside the veteran community that reflected the country’s broader sickness over the war. Tom Carhart, a prominent Vietnam veteran who led protests of Lin’s design, called the wall “an open urinal” when Lin unveiled her design.

But the memorial survived, and as years passed and the anger died down, Lin’s monument managed to serve its purpose as a center of healing. She’s been credited with a real accomplishment, overcoming one of the most scandalized and divisive parts of America’s history and eventually providing its foot soldiers of every rank, race and stripe with a place to meet again. The volunteers who stand guard at the wall have a lot of time to ponder the design and meaning of Lin’s memorial, and they don’t seem to tire of it.

The memorial is a living thing, kept alive by the sentries who volunteer there. But against the popular image of middle-age survivors of the hot part of the Cold War, they are getting older, replacing the Greatest Generation as the elder statesmen of America’s “warrior class.” And soon this war memorial, like all others, will outlive them.

A Good Day to Die

Fifty years ago, Mc Mahon was an unsuspecting college graduate who was getting married and preparing for a career in business. Like one-third of those who ended up serving in Vietnam, and unlike generations of young Americans since, he had no plans for a military career, but he got one anyway.

“This thing called Vietnam started to become real when I was in college,” Mc Mahon said. “My friends and I grew up as children of the Greatest Generation.” His father, every man on his block and every role model he knew was a World War II vet.

“There was a sense that if you were called to serve, you serve. I never thought of having a career in the military,” Mc Mahon said. What’s more, he thought he’d likely end up stationed in Germany, not Da Nang. This transformational power of the draft, once able to turn a lanky college grad into a platoon leader in Southeast Asia, is a part of American life that is increasingly unlikely to return.

Mc Mahon was drafted on Christmas Eve, 1968. “When you were drafted in New York, what they used to do is give you subway tokens — this was before MetroCard,” he said. “They’d put subway tokens in a letter, and when you got the letter you’d feel it. If you felt two tokens, you knew you were coming home. But when you were drafted, you felt one. You were going to Vietnam.”

The memorial is a living thing, kept alive by the sentries who volunteer there.

“I still have my letter,” he said, “and it has the one token.”

Still, Mc Mahon doesn’t much differentiate between those who were drafted and those who signed up. “I think people need to realize others wouldn’t have joined but for economic reasons,” he said. "There’s a lot of benefits you get from serving in the military. It was a way to pay for college, it was a way to pay for tuition.” Unlike the draft, the lure of the military for the poor and disenfranchised is a part of America that has not changed.

Mc Mahon didn’t fancy talking about his time in Vietnam. He swayed in the winter chill with his hands behind his back, snow beneath his feet.

“Some guys are very comfortable talking about it,” he said. “I do not talk about it.” Mc Mahon first began volunteering near his home in Holmdel, New Jersey, but in 2003, one of his friends told him to come down to sign up at Maya Lin’s wall in Washington. Now he drives down every month. “There’s lot of Vietnam veterans who find reunions ... this is my reunion. It’s what works for me.”

Mc Mahon joked to another vet volunteer passing by: “You can tell I’m from Brooklyn ’cause I talk a lot.”

The second vet was, like Mc Mahon, an Army guy. “Not voluntarily!” he noted with a laugh.

His name was Dan Kirby, and if Mc Mahon was uncomfortable bringing up his war tales, Kirby was uncomfortable keeping them in. Born in Arlington, Virginia, he visits the memorial to pay respects day by day. He tried to explain what it was like to be drafted into a war he never supported.

“Before being called up there were many, many discussions at the student union and local bars — among men and women alike,” Kirby said. “While I did not support the war, I felt like I did owe my country some sort of national service. My luck was that there was a rotten war going on.”

In April 1968 he got a letter from the Selective Service System that began, “Greetings.”

Kirby did well in training and, despite his personal opposition to the war, kept punching his ticket further. “My thought was to get this over with as quickly as possible,” he said. People he met who actually volunteered baffled him. “Even the infantry! This I did not understand.”

“When I asked why they had volunteered, most replied that they wanted to serve their country,” Kirby added.

His unit, stationed north of Saigon, suffered a shortage of junior noncommissioned officers, and Kirby became responsible for an entire squad of about a dozen men. His job was to search for enemy soldiers, patrolling assigned areas during the day and setting up night ambushes.

After three months in the field Kirby was wounded by a booby trap while leading a small patrol near his company’s perimeter.

“It was quite an experience, as I recall,” he said with wry detachment. “I didn’t hear anything. All I remember is lots of dust and rocks and smoke all over the place. Then I realized I couldn’t stand up.”

According to the men in his unit, Kirby was thrown into the air, a victim of a grenade in a ration can and a plastic explosive filled with nails.

“I just remember being on the ground, looking up into the blue sky and thinking, ‘Well, I guess this is as good a day as any to die,’” he said.

A couple of guys from his platoon ran over, soon joined by a medic. They cut off Kirby's boot to look at his legs and feet — the trap hadn't fully gone off, and his limbs were all intact. “Of course I wanted to get up and see, but they pushed me back down, told me I was gonna be OK.”

“Someone gave me a cigarette, I said thank you for that,” he said. “I thought, ‘If I can smoke, I’m gonna be OK.’”

A chopper carried Kirby to an evacuation hospital near a town called Cu Chi, where he rested for seven days. Every now and again he’d hear someone in the ward shout, “I’m goin’ home!” and the patient would be lifted off to Japan.

One day a nurse woke him up and told him to pack his things. “And I thought, ‘Oh, I’m goin’ home!’” he said. “No, no, you’re going back to your unit,” the nurse said.

“Well, f--- you very much,” he added with a chuckle.

Kirby was hurt badly enough to remain off the field, but not quite enough to be discharged. He handled a series of rear-echelon duties until his 12-month tour of duty was complete.

‘You Didn’t Know’

“You folks probably didn’t know, but you’re not supposed to walk in that area,” said Joe Follman, a four-year nonveteran volunteer at the memorial who teaches classes at Georgetown University. Two teenagers, one with a skateboard, apologized. “It’s alright, you didn’t know,” he said.

During his shifts, Follman notices the way different veteran volunteers handle the crowds. “Some are very open, friendly and jovial, some are more solemn,” he said. Some, like Kirby, are open about their politics and views (“I was baptized a Democrat”). Some, like Mc Mahon, refuse to go into that and stay on message about the beauty of the site. “Some of them, it’s like teachers who say schools would be better if there weren’t any kids in them,” Follman said, chuckling. “There’s some volunteers here who are kind of like that. They’d rather just be here alone.”

Follman, who incidentally studies volunteer programs in national parks, said there is something unique about the wall and its graying soldiers. “The Vietnam vets have a special dedication. I don’t think you can duplicate it,” he said. “These vets will come from all over the country on their own dime. One comes from Alaska.”

“If you volunteer down the road at the Smithsonian, you sign up from 4-8 doing a very specific job, and they count on you like a regular employee,” Follman added. “Here they don’t.”

Mc Mahon said he felt like Maya Lin’s architecture did more work to keep the memorial sacred than any volunteers could hope to do.

“Do we have the selfies? Yes,” he said. “And just as in New York, I’m sure, visitors from other countries. But it’s not often that I have to play the enforcer — ‘Don’t do this, don’t do that.’ It does happen, but for the most part, [the quiet] is just a natural part of the brilliance of the design.”

That brilliant design was once just another wartime wound on the ego of veterans, civilians and Maya Lin herself. The design earned an evocative list of derisive names: “a black gash of shame,” “a monument to Jane Fonda” and “Orwellian glop.”

“There was no heroic figure,” Mc Mahon said, admiring the design. “What you have is a black wall with the names of the dead and missing below ground. And everything in Washington is white and rises up.” Lin envisioned a giant knife cutting America open. The deepest section of the granite is 10 1/2 feet down beneath the earth. And when visitors scan the names of their friends or family, they see their own reflection in the black.

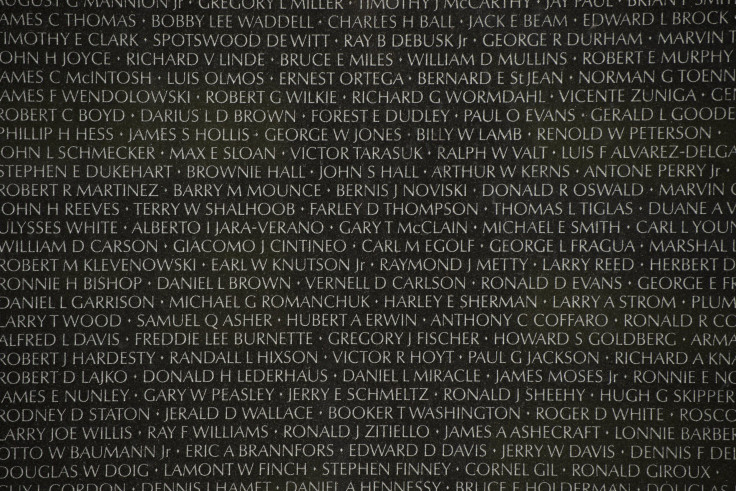

The names of the 57,661 dead and missing are assembled chronologically, from 1959, when the first advisers sent by President Dwight Eisenhower died, to May 15, 1975. There is no reference to rank, race, religion, gender or branch of service. As one veteran on the scene put it, “When you look for your friend, you find him by finding the date he died. The memorial is an open diary.”

You can often tell when the veterans served by where they stand. “It’s common to see a volunteer stand where they served,” a tour guide bellowed from across the lawn.

A name with a diamond next to it means the person is declared dead. A plus is for those still missing, which remains 728 people in total. When new dead are discovered, engravers come and transform the pluses into diamonds. Three diamonds were added this spring.

Mc Mahon mentioned there is no “heroic figure” in Lin’s design, but dissenting veterans got one anyway: After her plans were approved, the secretary of the interior mandated a compromise that included a more traditional monument across the lawn: a statue of three servicemen, one black, one white and one Hispanic. Later came another companion: a statue dedicated to the nurses who served during the war, eight of whom are on the wall.

Almost invisible is a small plaque on the walkway, set aside for those who died after they arrived home, from suicide, illness or Agent Orange and other poisons, which the United States dumped on enemy and friendly soldiers alike.

‘This Is My Reunion’

Upon arriving home, men like Kirby, Mc Mahon and Lazzaro were done with Vietnam, but Vietnam was not done with them. “Readjustment was not that easy,” Kirby said. “I did have a bit of a chip on my shoulder as I saw people going about their business as usual without making any sacrifices as our parents did during World War II. Yet here were men and women dying on a daily basis in Vietnam, and no one seemed to care.”

“I was angry and bitter,” Kirby said. He got himself back into college where he met other returning Vietnam vets. “This was a somewhat sheltered environment where we could share our experiences and feelings with people who knew what it was like.” After graduating from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1971 he embarked on a business career and retired from a local university in 2004.

Mc Mahon’s experience was also alienating: Not only was he drafted, he was also a replacement. “I did not go over with a unit,” he said. “A lot of the men who went over went as part of a group, they trained together, went over together, came home together, had their parade together. They decompressed together. They knew each other.”

“I went over alone. I wound up in a platoon, assigned to a squad, and I was going out on patrol with men I never met before,” Mc Mahon said. “And when I came home, I came home alone.”

That was not the experience of the WWII men, who Mc Mahon said enjoyed the respect of civilians and the camaraderie of former vets.

“You came home and it wasn’t popular to be a vet,” he said. “You put your uniform in your closet and you went on with life — little leagues and girl scouts and whatever else.”

On his first morning home he went to church, then went to breakfast with friends. They were anxious to hear all about Vietnam firsthand from the guy who came back. “The last thing I wanted to talk about was Vietnam,” Mc Mahon said. “But that loneliness, that isolation, I’m just thanking God I’m home. I wanna talk about what you’ve done for the last year, not what I’ve done for the last year.”

But like Kirby and Lazzaro, Mc Mahon eventually returned to his identity as a veteran through volunteering. “I retired and was like, ‘Now what do I do?’ One of the things that happened is, more of the [post-traumatic stress disorder] starts edging into your mind. So you start volunteering.”

But these men are getting older. And though he finds it hard to duplicate their commitment, Follman is optimistic that like the children of World War II veterans before them, the descendants of the Vietnam generation will show up to keep the memorial in good shape.

Lazzaro admits most of those on the park’s schedule are veterans, but said he sees younger people sign up all the time. “The girl that I work with is a college student. There’s a number of younger people.

“The majority of us are my age,” he said, finally cracking a smile. “You know, 25.”

Lazzaro said that like Mc Mahon, he returns to the wall out of a sense of belonging. But Kirby’s reasons for volunteering are wrapped up in the future as well as the past.

“When I think of the human cost on all sides I get very sad. Perhaps that is one of the reasons I volunteer,” he said. “I can make a bit of an effort to not forget those who served and died, and hope that there are lessons to be learned from the war in Vietnam.”

“I can hope,” Kirby said, “but given our recent adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan, I’m not always convinced.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.