What Happens When Police Turn Off Their Body Cameras?

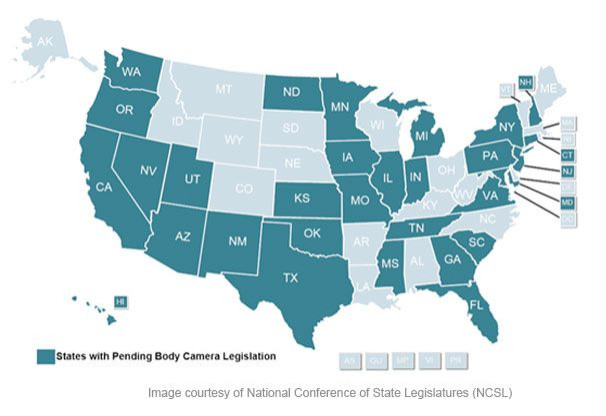

Body cameras are quickly becoming the most sought-after tech gadget in police departments across America. In the last five years, 34 states have considered new legislation that would require their police officers to wear body cameras, while six states -- Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, North Dakota and Utah -- have already implemented statewide programs.

But in the rush to outfit officers with cameras, a basic question lingers. An officer might be wearing a camera, but what happens when that officer doesn’t turn the camera on? And further, should there be a presumption of some kind of evidence tampering if the officer turned off -- or simply did not turn on -- the camera right before an incident?

A recent federal lawsuit in New Orleans could help answer this question.

In the early morning hours of Aug. 10, 2014, Armond Bennett, a 26-year-old security guard from New Orleans, was driving home with his brother. As detailed in a lawsuit filed earlier this month, Bennett and his brother pulled toward their home. There, they noticed a police cruiser parked down the street. As for what happened in the next few minutes -- it’s something of a "he said, she said."

Though New Orleans police officers are equipped with body cameras -- and are required to wear them at all times -- the following interaction was not recorded. Later reports stated that one of the officers involved -- Lisa Lewis -- was not wearing her camera because her shift was ending, while her partner simply did not have his turned on.

According to Bennett’s lawsuit, both officers “got out of the car with guns drawn,” approached Bennett and his brother, “who both had their hands up and visible to the officers.” The lawsuit goes on to state that Lewis “pulled open Mr. Bennett’s door and ordered him to get out of the car,” and “suddenly, and without reason, justification, or provocation ... pulled the trigger on her weapon and shot at Mr. Bennett.”

Bennett was shot in the forehead but survived.

The official police version, however, presents an altogether different portrayal of the events that night. According to NOLA.com, "Bennett got in a physical altercation with Lewis, again, and she fired two shots, one of which struck him in the forehead, police said." Lewis was suspended for one day for failing to wear her body camera, the New Orleans Advocate reported, and "was placed on administrative reassignment after the shooting and remains there, pending 'an ongoing criminal investigation.'"

'Uncharted Territory'

Obviously, footage from a police body camera would have been enormously helpful in understanding what happened that evening. Stephen Haedicke, the attorney representing Armond Bennett, suggests that because officers in New Orleans are required to record their interactions with the public, not recording the interaction could be tantamount to destruction of evidence.

“They had the ability to capture what happened on tape,” he says. “Not only the ability, but duty. ... That makes you go, why? If everything was on the up and up, then why not?”

Marc Blitz, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma who studies the legalities of body cameras, says few states have adopted specific laws that could address this very question. “It’s new technology,” he says. “So it’s uncharted territory.”

Blitz does believe, however, that there is a case to be made that if an officer intentionally turns off a camera before some sort of altercation, it could be treated in court as a destruction of evidence. “Just as courts often instruct the jury to presume that intentionally destroyed evidence was unfavorable to the party destroying it,” he wrote in a May report, “so they could instruct juries to presume that a gap in video footage of a police confrontation is unfavorable to a police officer who has turned off a body-worn camera or dashcam, unless that officer can supply a justification for turning off the camera.”

Cameras Not Rolling

Interestingly, shortly after last year’s shooting, an independent Louisiana review of police-worn body cameras in New Orleans looked at how often police were actually using the cameras. They found that “out of 145 ‘use of force events’ logged ... only 49 reports clearly indicated the event had been recorded.” In other words, police were wearing the body cameras -- but they weren’t turning them on.

To be sure, there are good reasons for an officer to be allowed to turn off the camera. For instance, Blitz notes that when an officer is speaking with a confidential informant, recording that interaction could put that person in danger. But so far, Blitz says, there are no federal rules on when to turn cameras on and off, so each state is left to set its own rules.

Maryland, for instance, announced just last week that it had formed a body camera commission that would govern the rules around when officers would be allowed to turn their cameras off. Blitz says that cameras should clearly be used during traffic stops and other interactions with the public. What’s less clear is if officers should be allowed to turn them off when interacting with minors or witnessing a rape or other sexual act.

"We are dealing with a technology that is literally in its infancy and moving at a very high rate of speed," Frederic Smalkin, a retired U.S. district judge, told the Maryland body camera commission Aug. 4. Smalkin is chairman of the panel.

Or, to use the words of the New Orleans' report, "Police cameras are useless if not used properly."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.