What Has The Curiosity Rover Taught Us About Mars So Far?

Curiosity, Spirit and Opportunity will have a little company in a decade or so. On Tuesday, NASA announced that it will be sending another rover to Mars in 2020.

"With this next mission, we're ensuring America remains the world leader in the exploration of the Red Planet, while taking another significant step toward sending humans there in the 2030s," NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said in a statement on Tuesday.

Curiosity's first months of exploration on Mars aren't exactly the same thrill ride as the rover's initial landing, a complex mechanical maneuver that NASA had dubbed “seven minutes of terror.”

But what has Curiosity found so far? In November, the press got into a minor tizzy when Curiosity scientist John Grotzinger told NPR that “this data is gonna be one for the history books.”

NASA representatives later clarified that Grotzinger was referring to the rover's entire two-year mission and not to any imminent revelation.

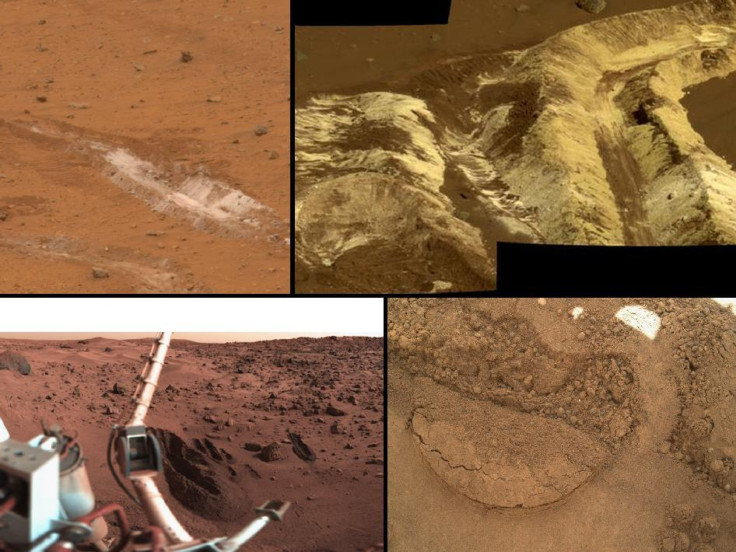

Even though it hasn't immediately stumbled upon the footprints of little green men, the mobile laboratory has already begun to probe the Red Planet deeper than ever before. The latest soil analysis from Curiosity takes small but important steps toward figuring out whether one of Mars' many craters could have ever supported extraterrestrial life.

A little scoop on the rover's arm allows it to take a closer look at Martian soil than any other instrument on the planet before. One of Curiosity's instruments is called SAM, which stands for Sample Analysis at Mars. SAM analyzes soil samples by heating them in a tiny oven and observing the gases that result. One of the signatures SAM is looking for is signs of carbon-containing organic compounds, which are one of the more important building blocks for life.

"We have no definitive detection of Martian organics at this point, but we will keep looking in the diverse environments of Gale Crater," NASA scientist Paul Mahaffy said in a statement on Monday.

Another Curiosity instrument called CheMin found that sand and soil scooped up from a dusty area of the Gale Crater called Rocknest is about half volcanic material and half other things, like glass. SAM also found signs of water in the sample, not a sign that Rocknest is wet, according to NASA. But the amount of water molecules found in the sample was higher than expected.

SAM also saw signs of the compound perchlorate, which is made up of an oxygen atom and four chlorine atoms. Perchlorate reacts strongly with organic molecules and was previously detected on Mars by the Phoenix Lander. The presence of perchlorate could explain why it might be hard for Curiosity to find any organic molecules on its mission.

“This does not mean Mars has life,” astronomer Phil Plait wrote for Discover Magazine in 2010. “But it does mean that if organic molecules are on Mars ... then they may get zapped by perchlorates. ... If perchlorates are common, this may make it less likely for us to find complex organic molecules.”

The perchlorate reacted with other chemicals inside Curiosity's little oven, forming organic compounds -- chlorinated methane compounds that contain one atom of carbon. But there's still a chance that the carbon may be from Earth, so NASA will have to conduct more tests to rule out that possibility.

Curiosity's successful landing, which was a tricky affair, since this rover was much larger than previous ones, also provides a blueprint for future missions. Whatever rover follows in Curiosity's footsteps (or is it wheel tracks?) in 2020 will likely be landing with systems based on it's predecessor.

“The challenge to restructure the Mars Exploration Program has turned from the seven minutes of terror for the Curiosity landing to the start of seven years of innovation,” NASA administrator and former astronaut John Grunsfeld said Tuesday.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.