Where Is Dark Matter? Fresh Analysis Of Fermi Telescope Data Fails To Reveal Traces Of Elusive Particles

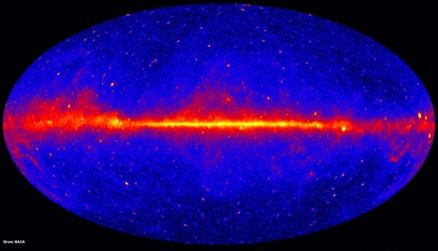

If our eyes could see gamma rays, the sky would never appear dark. No matter where we look, this high-energy radiation is always present, making it as ubiquitous as the cosmic microwave background — the radiation created shortly after the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago.

Although this Gamma-ray background radiation has been studied in extensive detail since the Fermi Satellite equipped with the Large Area Telescope was launched in 2008, its origin remains an enduring mystery. Many have theorized hidden within this so-called isotropic gamma-ray background may be signatures of the elusive dark matter, which makes up 85 percent of the universe’s mass.

Some theories about the composition of dark matter suggest that it consists of Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) that release high-frequency gamma rays when they annihilate each other. If this is true, this should lead to a gamma-ray excess — one that can’t be explained as originating from any known phenomenon.

Could the isotropic background of gamma rays be this smoking gun evidence of dark matter?

According to a new analysis of 81 months of data gathered by the Fermi Large Area Telescope, no.

“Our measurement complements other search campaigns that used gamma rays to look for dark matter and it confirms that there is little room left for dark matter induced gamma-ray emission in the isotropic gamma-ray background,” Mattia Fornasa, an astroparticle physicist at the University of Amsterdam and the lead author of a study describing the findings, said in a statement.

Most of the gamma rays detected by the Fermi satellite originates from within the Milky Way, and are produced from pulsars — which are rotating neutron stars — and supernovae. However, of the nearly 3,000 extragalactic sources of gamma rays detected by Fermi, nearly 75 percent are unaccounted for.

“One class of gamma-ray sources is needed to explain the fluctuations at low energies (below 1 GeV) and another type to generate the fluctuations at higher energy – the signatures of these two contributions is markedly different,” the University of Amsterdam said in the statement.

According to the researchers the high-energy sources are most likely objects known as blazars — cores of active galaxies oriented such that the high-energy jets being released by the regions around their supermassive black holes point directly toward Earth. The source of the low-energy emissions, however, is still not clear, as no gamma-ray emitters — including the hypothetical WIMPs — are believed to exhibit behavior consistent with the new data.

Although the study does not bring us closer to understanding where the gamma-ray background comes from, or where the signals expected from dark-matter annihilation are, it does help scientists rule out some models of dark matter than would have produced detectable gamma-ray signals.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.