White House Rejects Petition To Fire Aaron Swartz’ ‘Overzealous’ Prosecutors

The Obama administration’s decision to stand by the prosecutors who brought criminal charges against Internet activist Aaron Swartz by rejecting a petition for their ouster brings closure to a case that tragically ended in Swartz’ suicide and tested the White House’s commitment to maintaining “a spirit of openness” around the Internet. But Swartz’ backers say the aggressive prosecution of an individual for downloading what they see as the digital equivalent of library books will long have a chilling effect on research and Internet freedoms.

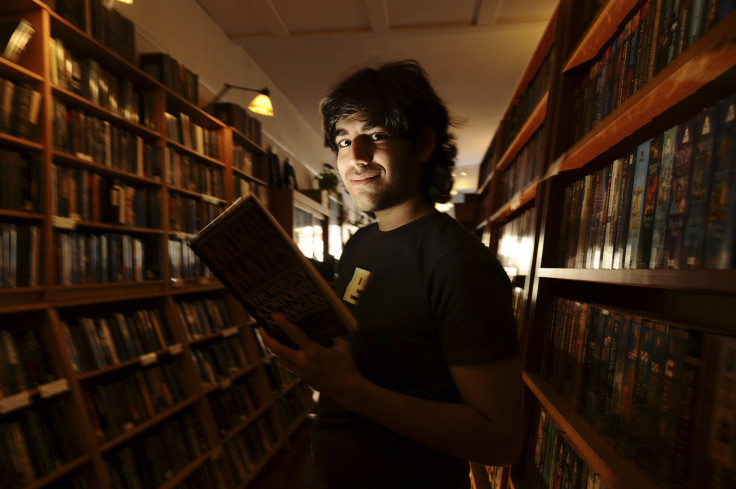

Swartz, a self-described “hacktivist” and political organizer who helped create the RSS format and was heavily involved with the Creative Commons organization, took his own life on Jan. 11, 2013 in his Brooklyn, New York, apartment just before he was due to stand trial for on charges of violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

He was accused of downloading troves of data from the academic database JSTOR, which charges for access, and spreading the files online. The prosecutors in the case, U.S. Attorneys Carmen Ortiz and Steve Heymann in Boston, were widely criticized in the wake of Swartz’ death for seeking the maximum prison sentence of 35 years.

“From the beginning, the government worked as hard as it could to characterize what Aaron did in the most extreme and absurd way. The ‘property’ Aaron had ‘stolen,’ we were told, was worth ‘millions of dollars’ – with the hint, and the suggestion, that his aim must have been to profit from his crime,” Lawrence Lessig, the noted legal thinker, Harvard law school professor and mentor to Swartz, wrote in an impassioned blog post that summed up the raw feeling prevalent after the young man's untimely death.

“But anyone who says that there is money to be made in a stash of academic articles is either an idiot or a liar. It is clear what this was not, yet our government continued to push as if it had caught the 9/11 terrorists red-handed.”

The emotions surrounding Swartz’s death led to a We the People petition calling on the White House to fire Ortiz and Heymann. The petition quickly earned an official White House response by passing the required threshold of 25,000 signatures.

On Wednesday, the White House formally rejected it. “As to the specific personnel-related requests raised in your petitions, our response must be limited,” it stated. “Consistent with the terms we laid out when we began We the People, we will not address agency personnel matters in a petition response, because we do not believe this is the appropriate forum in which to do so.”

The White House went on to “reaffirm our belief that a spirit of openness is what makes the Internet such a powerful engine for economic growth, technological innovation and new ideas.”

For many, that fine sentiment was undermined when one of the brightest technological minds in a generation was threatened with decades behind bars for disseminating obscure academic journals. That threat has contributed to a chilling effect at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Swartz was arrested after allegedly using MIT’s campus network to download the JSTOR articles. MIT students admitted to Boston magazine last year that they’ve been hesitant to share their opinions about the case – and the school’s handling of it – through official MIT forums online.

The wider effect of the Swartz case runs much deeper, according to Chris Ott, communications director at the Massachusetts office of the American Civil Liberties Union. Ott said students and academics may start self-censoring before sharing opinions or research online.

“I think there is a real danger of a chilling effect,” he told IBTimes. “We were struck by the disparity in Aaron’s sentence compared to how people who are responsible for the financial collapse have been treated, or people involved with torture. There’s a real discrepancy here, and who wouldn’t be concerned by the threat of such a long prison sentence imposed on them?”

In addition to the prison term, Swartz was potentially facing a fine of up to $1 million at the time of his suicide. A documentary about his life, “The Internet’s Own Boy,” is now available on YouTube.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.