Why Is China Devaluing Its Currency? US Lawmakers Call It Manipulation, Others See China Moving Toward Free Markets

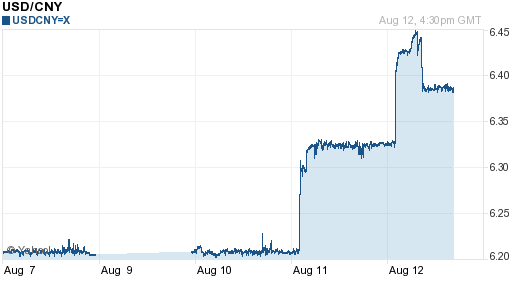

Global markets got a jolt this week from the People’s Bank of China, which abruptly moved to devalue its currency, the yuan. On Tuesday, the currency fell 1.9 percent against the dollar. On Wednesday, the day ended with the currency at 6.3838 yuan to a dollar, a further 1.8 percent decline.

Rattled investors sent markets around the world sliding. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 212 points Tuesday, down 1.2 percent. And by noon Wednesday, the Dow had dipped to a 2015 low. Some worry the move could precipitate a “tidal wave” of similar moves throughout Asia and the world economy.

But reactions among economists are split. The International Monetary Fund already welcomed the news, which it cautiously hailed as “a welcome step” that would “allow market forces to have a greater role in determining the exchange rate.”

In contrast, U.S. lawmakers looked askance at the devaluation. Senators including Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., have long charged China with gaining an unfair advantage in global markets by manipulating its currency. Artificially depressed currencies bolster exports and protect domestic markets.

“Rather than changing their ways, the Chinese government seems to be doubling down,” Schumer told the New York Times.

In a further complication, the Chinese central bank intervened in the final minutes of trading Wednesday to keep the yuan from spiraling into free fall, proving the limits of Beijing’s patience with market moves outside its control.

These vacillations, which will have wide-ranging global ripple effects, reflect a Chinese government navigating the transition from a heavily controlled monetary system to a player in free global markets. It won’t be an easy ride.

How Does The Yuan Work?

For decades, China pegged the yuan firmly to the dollar. In the 1980s, however, the government undertook massive devaluations to make trade more attractive. The economy exploded, and eventually the yuan was frozen again. Facing international pressure a decade later, China let the currency appreciate in 2005. The yuan has since strengthened by more than 20 percent.

Viewed in historical context, the recent moves in the yuan are miniscule.

But the currency is hardly free-floating. Beijing uses a number of measures to control the value of the yuan. According to official guidelines, the yuan may trade only 2 percent above or below a midpoint set daily by the central bank. On Tuesday, the bank announced it would set that midpoint to a level referenced to the previous day’s trading, putting it more in line with supply and demand.

To hem in yuan prices, the PBOC keeps an arsenal of nearly $3.7 trillion in global currencies to deploy as the need arises. When the bank stepped in to prop up the yuan Wednesday, for instance, it did so by directing state-owned banks to sell massive quantities of dollars, taking yuan off the market. These huge trades cow investors hoping to exchange their yuan for greenbacks, giving the Chinese note a lift.

What Does China Want?

China has a number of motivations that are aligning. Its economy has been slumping, with recent economic news showing an industrial slowdown. A devalued yuan means foreign countries can buy Chinese goods more cheaply. Meanwhile, domestic Chinese manufacturers benefit as the cost of importing goods grows.

“I think that’s a red herring,” says Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The Chinese economy has been slowing for years, he points out, and a 2 percent cut is hardly enough to juice slow-moving markets.

A potentially more convincing explanation is China’s quest for global monetary sway. China wants the yuan eventually to challenge the dollar as a global reserve currency. That has Beijing eyeing the IMF’s special drawing rights basket, the group of currencies the fund holds as reserves. The dollar, the British pound sterling, the euro and the yen currently make the cut.

Lardy points out that the IMF meets in November to decide whether to add the yuan to the basket. “They’re stepping up with more transparency with their reserves, all steps to make market participants feel that the [yuan] is going to be an international currency.”

But to join the exclusive club, China needs to show the IMF it won’t meddle too much with its currency. That’s why the move Tuesday to free the reins on the yuan drew kind words from the IMF -- and why Wednesday’s eleventh-hour infusion of support muddies the waters.

What Do Others Want?

Investors often bemoan the heavy hand of the Chinese government in its currency and markets; therefore, some welcomed the recent moves to let the yuan more freely ride the waves of global finance.

In its note of approval for China’s devaluation, the IMF encouraged Beijing to “aim to achieve an effectively floating exchange rate system within two to three years.”

But other large exporting economies might not be so happy. A cheaper yuan means more countries will seek to import from China, hurting manufacturers elsewhere. American lawmakers, who have prodded Washington to designate China as a currency manipulator, argue that points shaved off the yuan mean jobs lost in the U.S.

Lardy finds the argument contradictory. “You can’t say you’re in favor of [the yuan] being more market-determined, but only if it appreciates,” he says.

What’s Next?

It’s too early to tell how deeply China’s commitment to a freely traded yuan will extend. In a statement explaining the move, the PBOC assured that the move wasn’t an effort to boost its economy. It did not promise, however, to refrain from further intervening in its currency. Moving forward will likely be a balancing act between maintaining strict control and pleasing international authorities.

Lardy cautions against making firm predictions. “If you’re China, you can’t move to just the market overnight.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.