Women In Tech Industry Few And Far Between, And Some Say Male Prejudices Are To Blame

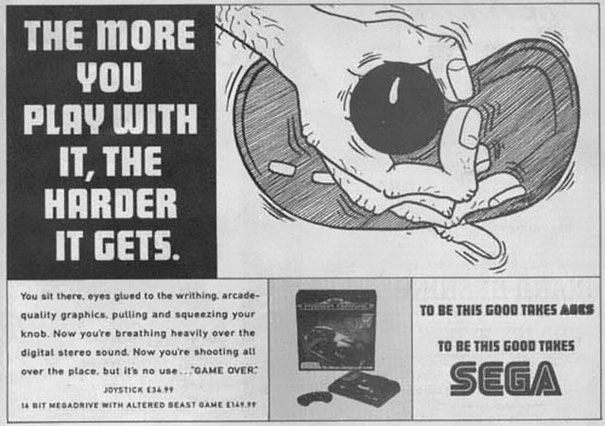

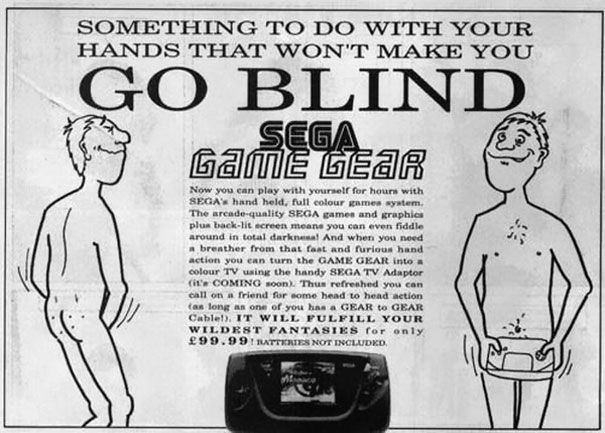

In the 1980s, video games were meant for boys. Sega, Nintendo’s biggest rival at the time, went so far as to advertise its joystick controller and Game Gear handheld console with tongue-in-cheek male masturbatory references.

It was generally accepted that boys played with "boy toys" like Erector sets, Legos and Lincoln Logs, and girls played with "girl toys" like Barbie dolls, American Girl dolls and Easy-Bake ovens. Twenty-five years later, men and women play video games at roughly the same rate, but the gender gap remains in full effect within the industry itself. Women in tech are still rare, and some say old stereotypes and prejudices are to blame.

Both Yahoo, which released its Equal Employment Opportunity statistics this week, and Google, which released its own employment information in late May, have surprisingly low employment rates for women -- 37 percent and 30 percent, respectively. Yahoo -- a company run by one of the smartest and most powerful women in tech, Marissa Mayer -- and Google both separated out non-tech roles such as human resources and public relations and came up with an effective 15 and 17 percent women in tech roles, respectively.

Google Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) and Yahoo Inc. (NASDAQ:YHOO) have acknowledged that their female representation is drastically low but argue that it is because of a problem with applicants: There aren't enough women applying.

We’re not where we want to be when it comes to diversity. - Google

The presumption is that women just aren’t interested in tech, which to a certain degree is true, but not for the reasons one might think.

“It was never a welcoming environment,” Mary Flanagan, a Dartmouth College professor and founding director of Tiltfactor, a software and gaming research laboratory based in New Hampshire, said of the 1990s gaming industry. According to her, “There was still porn on the walls.”

While gaming has grown to become a multibillion-dollar industry and has attracted women around the world -- 45 percent of active console gamers are now women -- representations of women on screen still tend to be hypersexualized, which, according to Flanagan, comes from a lack of diversity on the developer side.

But how can a company have diversity when only approximately 25 percent of computer science or engineering degrees go to women?

The problem starts with education, specifically youth education, Karen Purcell, an electrical engineer who has owned her own engineering company in Reno, Nevada, for 18 years, said.

“In the educational industry, there is still this bias that exists,” Purcell said. Her own daughter just graduated from middle school, she added, and, “Boys are definitely pushed toward traditional male careers or male interests, whereas girls are pushed toward traditional female careers.”

Those careers include health care, teaching and soft sciences such as psychology. According to the National Science Foundation, of the 80,000 female graduates of 2008 in science, 33,000 were in psychology; there were only 22,000 female computer science and engineering graduates combined.

Purcell, who recently published the book "Unlocking Your Brilliance: Smart Strategies for Women to Thrive in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math," claims gender bias in engineering is still prevalent.

“If I go out to a job site where one of our projects is being constructed and the contractor doesn’t know me, they instantly assume that I’m the assistant, that I’m not the engineer,” Purcell said.

Mistaking a woman for an assistant instead of the head engineer may not seem like a big deal -- perhaps just a social gaffe -- but the fundamental issue is potent. By limiting the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) world to a male-centric view, hypermasculine personalities can thrive, leading some to say the industry essentially condones misogyny.

As evidence, critics point to Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel. In late May, Gawker site ValleyWag published a list of emails from Spiegel during his freshman year at Stanford, just four years ago, in which he discussed having drunken sex, urinating on women and using jello shots to encourage “frigid” sorority girls to have sex. Spiegel, 24, turned down a $3 billion acquisition offer late last year from Facebook Inc. (NASDAQ:FB), according to the Wall Street Journal, which cited people briefed on the matter.

Also notable was Rap Genius co-founder Mahbod Moghadam’s annotation of Elliot Rodger’s manifesto, a 141-page document that blames women for the killing of six University of California, Santa Barbara students in mid-May. Moghadam called the manifesto “beautifully written” and went so far as to sexualize Rodger’s sister by saying, “MY GUESS: his sister is smokin hot.”

The other founders of Rap Genius saw the annotation for what it was and fired Moghadam.

The mindlessness that both Spiegel and Moghadam showed in their actions exemplifies the need for change in what Andrea Rees Davies, associate director of Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research, and Caroline Simard, associate director at Stanford’s Office of Diversity and Leadership, call gender bias.

“Gender bias is based on cultural norms,” Davies said in explaining the belief that “a lot of what makes a good programmer is male,” is further evidence of gender bias.

Davies believes that the tech fields aren’t maliciously misogynistic, but that gender bias is so ingrained it is a natural mentality for men -- and women -- to have. Even young girls believe that computer science isn’t an appropriate field of study for them, she said.

“Finding ways to change gender bias, changes representation,” Simard said, noting that representation is directly linked to diversity.

By having a diverse workforce, businesses benefit from multiple perspectives, Purcell said.

Women and men have different priorities, observed Ari Horie, founder and CEO of Women’s Startup Lab, a Silicon Valley startup accelerator that focuses on female entrepreneurs. Horie noticed that traditional accelerators, where startups go to get advice and training in an intensive program, focused on competition between the entrepreneurs. Competition is an inherently male mentality, Horie argues.

“That model works with a very specific demographic,” Horie said.

Instead, Women’s Startup Lab works collaboratively, which Horie considers an approach women are more drawn to -- turning to others and seeking help, rather than trying to best each other. Horie added that her model isn’t better or worse than the traditional one, just different.

In March, Horie was voted one of CNN’s 10 Visionary Women.

While Horie is working toward giving female-led tech startups opportunities, the lack of diversity starts before young girls turn 13, according to a recent Mother Jones report that pointed out “research shows that girls tend to pull away from STEM subjects -- including computer science -- around middle school, while rates of boys in these classes stay steady.”

Ultimately, there isn’t a simple solution, but there are some promising ideas. Last spring, the University of California, Berkeley, undertook what many considered an unlikely effort, but it worked. An introductory computer science class attracted more than 50 percent female student enrollment after the university changed the name of the class. "Introduction to Symbolic Programming" became "Beauty and the Joy of Computing" and the female enrollment rate jumped. Changing the name eliminated a stigma that computer science is more appropriate for males. The language was no longer male-centric. Horie believes we use male-centric language unintentionally, which deters women from exploring science and tech.

“If you want to have diversity,” Horie said, “we have to make conscious effort to question every part of it, the way they talk, the culture that they set up at the corporation, and the number of employees that are reflecting the culture.”

While it's easy to blame misogynistic mindsets, poor education and lack of encouragement for young women or even the rhetoric used in STEM (all of which are very real problems), in the end, Horie, Purcell, Flanagan, Davies and Simard all agree on one thing: More female role models are needed in science and technology.

“I think that if there is a role model,” Purcell said, “if these girls can be exposed to anyone -- doesn’t have to be someone famous, but anyone in these fields -- they see ‘look, she can do it, so can I.’”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.