Your Breast Cancer Risk Not Linked to Your Mother’s, Say U.S. Researchers

The likelihood of contracting breast cancer need not run through family lines, contrary to popular belief. According to new research, it is being suggested that women may not run the risk of breast cancer if their mothers or other members of the family test positive for genetic mutations of the same.

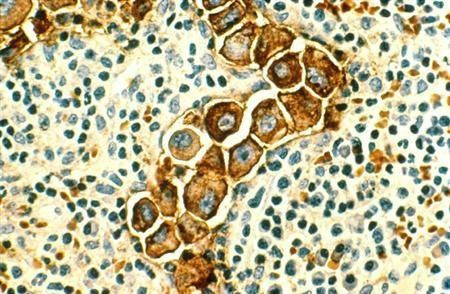

The study, the results of which were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, suggests that close relatives of women who carry mutations in a BRCA gene but who themselves do not express such genetic mutations may be spared an increased risk of developing breast cancer. This is in comparison to women whose relatives with breast cancer do not reveal such mutations. The new findings, therefore, suggest that women who test negative for the mutation may not need extra cancer screening and increased preventive measures.

The new result is an encouraging breakthrough since it is known that between 5 and 10 percent of all instances of breast cancer are genetic in nature. In most cases, the cancer is caused by abnormalities in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Women with these mutations are 20 times likelier to develop breast or ovarian cancer and must undergo intensive screenings and take other precautions to reduce their cancer risk. Many of these women elect to have their breasts or ovaries removed to keep from developing cancer.

The new results overrules a 2007 study that indicated first-degree bloodline relations such as mothers, sisters and daughters of women with BRCA gene mutations to be several times more prone, than the general population, to develop breast cancer, despite not having the mutation themselves.

This new study gives reassurance to non-carriers that they do not have an increased risk due to the familial mutation, and should be regarded the same as other non-carriers with first-degree relatives who have had breast cancer, said lead author Allison Kurian, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Health Research and Policy at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

One strength of the current study is the control women it used as a yardstick for comparing the breast cancer incidence in non-carriers of family-specific mutations. The control women were also relatives of breast cancer patients, but of patients without mutations. This is a more appropriate yardstick than average risk in the general population, since close relatives of all breast cancer patients have somewhat higher than average risks, she added.

Kurian said the studies had looked at women who were in cancer family clinics and compared their breast cancer risk to that of women in the general population. Women from cancer family clinics were more likely to have intensive screening and breast cancer risks tend to be higher among close relatives of breast cancer patients than those in the general population.

Earlier reports of higher risk among non-carriers of family-specific BRCA mutations compared to risks in the general population may reflect a comparison of women with and without a family history of breast cancer, said Alice Whittemore, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The control group we used - relatives of breast cancer patients in families without a BRCA mutation - was important. The results suggest that women who test negative for their family's BRCA mutation have no greater breast cancer risk than a woman who also has relatives with breast cancer but no family-specific mutation, added Whitmore.

The investigators studied women from 3,047 families (each woman had breast cancer) in three population-based cancer registries in Northern California (1,214), Australia (799) and Canada (1,034) through a consortium called the Breast Cancer Family Registry. They found 292 families in which a woman had a BRCA mutation. This is the largest analysis, to date, of the breast cancer risk of non-carriers of family-specific BRCA mutations. They compared the risk of breast cancer among first-degree relatives of breast cancer patients who did and did not carry a BRCA mutation and found no significant difference. This means that non-carriers of a familial BRCA mutation did not have a markedly elevated risk of developing breast cancer.

The investigators also found that a small percentage of women (approximately 3.4 percent in the general populations of Australia, Canada and the U.S.), for unexplained reasons (aside from a BRCA mutation), accounted for approximately 32 percent of all breast cancer cases, reflecting the wide range of factors that could play a role in breast cancer development. Recent research suggests that many different genetic variants affect breast cancer risk and that the women at highest risk have inherited many of these variants.

Many patients and their physicians incorrectly apply the same standard for screening and risk-reducing intervention for mutation-negative, first degree relatives as for mutation positive individuals. This work underscores that the risk for developing breast cancer is considerably lower in women who do not carry a BRCA mutation. Raising awareness of these findings could serve the public well in dissuading some women from unwarranted and excessive screening and/or risk-reducing interventions, summarized Andrew Seidman, MD, ASCO Cancer Communications Committee member and breast cancer specialist.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.