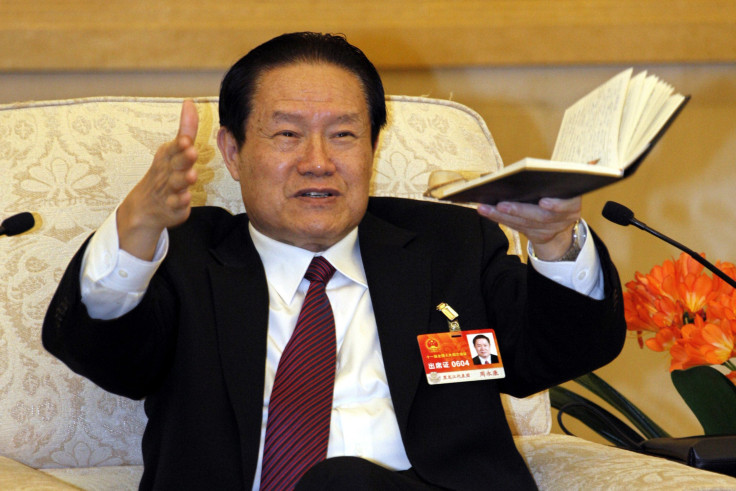

With Zhou Yongkang's Downfall, Xi Jinping Becomes Most Powerful Chinese Ruler In Decades

Tuesday’s announcement that Zhou Yongkang, once one of China’s most powerful politicians, is under official criminal investigation came as little surprise: Communist Party officials had already detained several of Zhou’s relatives and associates over the past several months, and the man himself had not appeared in public since last October. He had retired from the Politburo's Standing Committee in 2012.

But despite the anti-climactic and vague nature of the announcement -- Xinhua, China’s state-run news agency, simply reported that he is under investigation for apparent “discipline violations” -- Zhou Yongkang’s downfall is a major political development in China. If convicted -- a near-certainty in China’s justice system -- he will be the most senior official removed in a corruption scandal since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

Zhou’s purge marks the most significant inflection point in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, which has emerged as the central feature of his tenure. Since assuming China’s top office in November 2012, Xi has ordered Communist officials to curtail ostentatious displays of privilege, such as luxury cars and lavish banquets, that had roused widespread public anger. The president has also vowed to go after both elite and lowly party members -- so-called “tigers and flies” -- who engaged in corrupt practices.

Until now, the most significant tiger nabbed in the campaign was Bo Xilai, the charismatic former party secretary of Chongqing who was convicted of bribery, abuse of power and corruption during a high-profile trial last August. The nature of Bo’s crimes -- he had attempted to cover up his wife’s murder of a British businessman -- electrified China’s staid political scene. But Zhou Yongkang’s removal may ultimately be of far greater significance.

Born into an impoverished family in 1942 and trained as a geologist, Zhou rose through the ranks of China’s oil and gas industries, assuming control of the China National Petroluem Corporation, a state-run giant. Zhou then leveraged his connections in government to be appointed party secretary of Sichuan province, and, four years later, took control of China’s vast domestic security apparatus, a government division whose $110 billion budget exceeds that of the People's Liberation Army.

It is in this role that Zhou’s power grew. He gained control over China’s police, intelligence and court systems, and assumed responsibility for repressing dissent. In 2007, Zhou maintained this portfolio as a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, China’s highest political entity. He had become, as the Financial Times put it, a Chinese combination of Dick Cheney and J. Edgar Hoover.

During his years in public service, Zhou’s family and associates amassed a fortune estimated at 90 billion yuan, or $14 billion. While little of this money was tied directly to Zhou, a New York Times investigation from April revealed how close relatives, including his son Zhou Bin, leveraged Zhou Yongkang’s oil and gas industry connections to land lucrative contracts.

“Because of Zhou’s connections to energy, land and the internal security system, in effect the family had kind of carte blanche to go into anything they wanted,” Andrew Wedeman, an academic specializing in China, told the Times.

Zhou Yongkang is hardly the first senior Chinese official to amass a fortune in office. Associates and relatives of Wen Jiabao, who served as premier from 2002 to 2012, accumulated a combined $2 billion in wealth, according to a New York Times investigation. Those tied to Xi Jinping himself have also earned millions through various business interests, according to an investigation by Bloomberg News. Zhou also avoided the sort of high-profile scandal that led to the downfall of Bo Xilai.

Why was he -- rather than someone else -- singled out for corruption?

The reason lies partly in the complex interplay of Chinese politics, where, despite an external appearance of unity, factions compete for power and influence. Zhou was a close associate of Jiang Zemin, China’s president from 1989 to 2002 and still a man who wields significant influence within government. While Jiang initially supported Xi Jinping’s efforts to stamp out corruption, the ex-president reportedly warned Xi that the “footprint” of the campaign “cannot get too big.”

Xi has consolidated power in other ways. Unlike ex-President Hu Jintao, who waited two years to assume chairmanship of the key Central Military Commission, Xi was named to the post at the same time he became president. Also, by chairing the Central Leading Group on Finance and Economics, Xi has usurped control over economic policy, a portfolio normally held by the prime minister.

So is Xi’s anti-corruption campaign a sincere attempt to steer China toward reform, or a cynical power grab?

Samm Sacks, a China analyst at Eurasia Group, believes that by consolidating power, Xi is better placed to push through structural reforms in the Communist Party's top-down system. The president’s inspection campaigns, introduced in cities across 10 provinces, have improved Beijing’s oversight of provincial and local governments.

“The leadership sees the anti-corruption campaign as critical, and believes that if China doesn’t rid the bureaucracy of fraud and waste, it’ll stand in the way of necessary changes in China’s political culture,” she said.

“The campaign is China’s largest political shake-up since [the crackdown in] Tiananmen Square in 1989.”

Yet Xi’s strategy of curtailing corruption remains very much a top-down affair. Under his administration, media censorship has tightened. And when Xu Zhiyong, a prominent anti-corruption activist, called for the release last year of 10 citizens arrested for protesting corruption, Xu himself was detained.

Examples like these, argues Murray Scot Tanner, a China analyst at CNA Corporation, a non-profit research and analysis organization, show that Xi’s campaign may have more to do with removing potential threats to his power. Despite the high-profile case of Zhou, corruption arrests on a national scale remain modest.

“The acid test will be when Xi takes down senior leaders who are publicly known to be affiliated with him,” he said.

As for Zhou Yongkang, a trial -- and conviction -- are almost certain. But Sacks believe that Zhou’s downfall, as significant a milestone as it is, is likely just a prelude for a larger, more extensive anti-corruption crackdown.

“I think the important thing here (is that) the anti-corruption campaign is systemic, and lasting, and is not episodic … it isn’t just targeting isolated officials that are seen as to opponents to Xi Jinping,” she said.

“The campaign is escalating.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.