2012 Solar Storm Could Have Been More Extreme: Here’s How

KEY POINTS

- In 2012, an extreme solar storm nearly hit the Earth

- Researchers studying the event said it could have been more extreme if paired with another event

- Researchers demonstrated how two solar storms could interact with each other

Solar storms could become more powerful if they happen quite close to each other, researchers studying the 2012 solar storm have found.

On July 23, 2012, a solar storm, which NASA describes as the most powerful one in about 150 years, nearly hit the Earth. Had it hit the Earth, it would have caused an economic impact of over $2 trillion and the damages could take years to repair.

The 2012 near-miss has been likened to the 1859 Carrington Event, one of the biggest solar storms on record, that caused auroras as far south as Cuba and Honolulu.

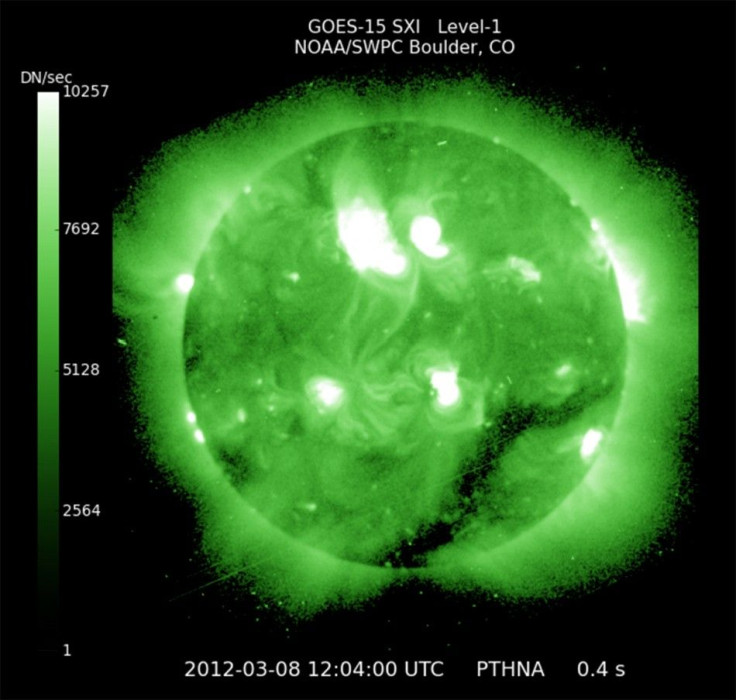

Coronal Mass Ejections (CME) are outbursts of plasma from the sun that release large amounts of energy. When CMEs reach the Earth, they can affect its magnetic fields, creating stunning auroras. They can also potentially disrupt satellites, GPS systems and power grids.

In a new study published in Solar Physics, a team of researchers studied the 2012 near-miss and found that it could have been a more extreme event if it happened just a little bit earlier.

"The 23 July 2012 event is the most extreme space weather event of the space age, and if this event struck Earth the consequences could cause technological blackouts and severely disrupt society, as we are ever more reliant on modern technologies for our day-to-day lives," Dr. Ravindra Desai of Imperial College London said in a news release. "We find however that this event could actually have been even more extreme – faster and more intense – if it had been launched several days earlier directly behind another event."

The team studied a large CME that occurred on July 23, 2012. Researchers said one CME could essentially "clear the way" for another, and hence, an earlier CME that had disrupted the solar wind could allow a second, subsequent one to move much faster without being slowed down by the solar wind. Dr. Desai said there was actually an earlier CME on July 19, just days prior to the near-miss event, from the same active region.

Using a model to represent the July 19 and July 23 CMEs, the researchers tested what would have happened if the July latter had happened closer to the July 19 event. They found it would have reached speeds of up to 2,750 kilometers (1,708 miles) per second or perhaps even more. By comparison, the actual event was estimated to be of about 2,250 km per second.

The two solar storms would have affected each other, with the earlier solar storm giving way for the second one to move with an advantage. But since the July 23 event happened a bit later, the solar wind had "nearly fully recovered" from the previous event by the time it erupted, thereby slowing it down.

"There is always the possibility of similar or worse scenarios occurring this next solar cycle, therefore accurate models for prediction are vital to help mitigate their effects," study co-author Emma Davies, also from Imperial College London, said in the news release.

This is why agencies such as NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are continuously watching space weather and updating the technology used to predict space weather.

Only recently, experts announced that the Solar Cycle 25 has already begun but it may be a rather mild one. But despite this prediction, scientists are still keeping a close watch on the sun as there is still no guarantee that a below-average cycle would not result in extreme space weather.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.