Afghan Presidential Election 2014: Why Pro-Western Candidates May Not Align With US Interest

Of the 11 candidates running in the April 2014 Afghan presidential elections, you'd think the U.S. would prefer one who's more pro-Western over a former warlord with blood on his hands. But the complex political and ethnic divide that characterizes Afghanistan may mean that none of the candidates would align with U.S. interests, according to an expert on U.S.-Afghan relations.

Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow with the Foreign Policy program at Brookings, a nonpartisan Washington think tank, said there are two types of candidates: technocrats and former warlords. Each has weaknesses as well as strengths.

On the one hand, technocrats may be far more motivated to improve Afghanistan's corrupt and ineffective government, but they may have a harder time implementing policies because of their weak power base.

On the other hand, former warlords have widespread and complex networks, giving them far more capacity to implement policy than technocrats have.

In order for technocrat candidates like Abdallah Abdallah, Dr. Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai and Zalmai Rassoul to have any chance of winning, they will have to cut deals with certain unsavory power brokers who carry a lot of influence. In return, they would to some extent be beholden to those power brokers, whose interests could conflict with U.S. interests.

“I think in principle all three candidates have credentials and a sense that they are politically far [more] aligned with U.S. relations,” Felbab-Brown said. “But the great uncertainty about them lies in whether they will have any capacity to implement anything.”

For example, Ahmadzai's vice presidential candidate is his former archenemy General Abdul Rashid Dostum, a powerful Northern warlord. Dostum is a highly controversial figure. Ahmadzai, who called himself the "most virtuous candidate" in the 2009 Afghan elections, is now in bed with a man who has a “problematic human rights record.”

Current president Hamid Karzai is no different, as he is also beholden to extremely controversial groups -- one of them Hezbi-Islami, a militant group responsible for a February suicide attack that killed two coalition contractors and wounded several Afghan civilians.

Some suggest that Karzai’s anti-American attitude and his “delusional strategic perspective is an expression of just how much power Hezbi-Islami has over him,” Vanda-Brown said.

While technocrats may seem the best option from a Western point of view, it still does not mean they would implement policies that promote U.S. interests. Conversely, people who were aligned with the Taliban may now be their adversaries.

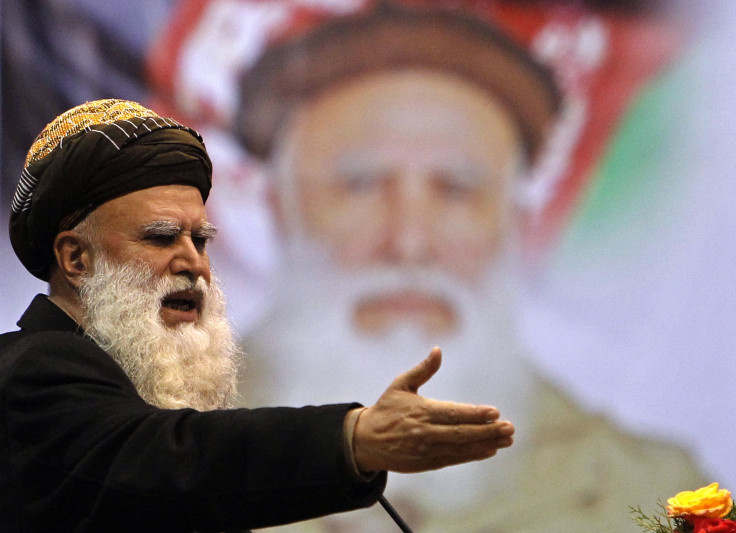

Take Abdul Rab Rassoul Sayyaf, one of the frontrunners in the election and a conservative ex-warlord, who was a mentor of Khaled Sheikh Mohamed, the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks. He is now an enemy of the Taliban, who actually want him dead.

Sayyaf may have an anti-American agenda, Felbab-Brown said, but he acknowledges the importance of having a small U.S. contingent force to hedge against the Taliban after the planned withdrawal of U.S. and international troops by the end of 2014. Sayyaf feels so threatened by the Taliban’s resurgence that he is willing to overlook a U.S. force.

He also has a lot of support from the younger generation in cities, but not because of any religiosity. Rather, they support him because of his powerful influence and ability to implement policies where others have failed.

"It just shows you the extraordinary fluidity and the shifting positions," Felbab-Brown said.

Whether a technocrat or former warlord is elected, Vanda-Brown suggests that the U.S. should not get "trapped in the notion" that one candidate is better than the other. Instead, the U.S. should help improve the stability of the Afghan government while continuing to promote U.S. interests there.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.