African Union Summit 2016: In Burundi, A Loss Of Faith In Peace

As a young man living in Burundi’s war-torn capital, Kavuyimbo fears for his life. The 28-year-old freelance journalist has been hiding at a friend’s residence for weeks following a police raid at his home and others in the Musaga neighborhood of Bujumbura, while searching for opposition members. Kavuyimbo, who did not give his real name for fear of reprisal, said he leaves the house only on Sundays to attend church nearby where he prays for peace. His faith, though, in seeing an end to the violence is waning.

“It’s very, very scary in Burundi,” he said in an interview Monday. “We can’t sleep some nights because of gunfire.”

The African Union, a 54-member continental bloc, had said it would send a 5,000-strong peacekeeping force to quell the violence in war-torn Burundi, with or without the government’s consent. It backpedaled on that plan Sunday, instead announcing a deployment of high-level delegates to Bujumbura to negotiate a solution acceptable to President Pierre Nkurunziza. But the Burundian leader is unlikely to approve foreign boots on the ground under any circumstances, political and human rights experts said, leaving violence to continue unabated and tipping the central African nation closer to a civil war.

“This seems like a missed opportunity,” said Cara Jones, an assistant professor of political science at Mary Baldwin College in Virginia who researches Burundi. “Is this a failure for the African Union? It’s certainly not a success.”

The crisis began in April when Nkurunziza, a former Hutu rebel, said he would seek for a third term as president. Critics said Nkurunziza was violating the constitution and a peace deal that ended 12 years of civil war between Burundi’s Hutu majority and its Tutsi minority. But the ruling party said Nkurunziza’s first term does not count because he was appointed by Parliament rather than elected in 2005 following the peace accord. Demonstrations against Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term broke out, and violent clashes erupted between protesters and forces loyal to the ruling party. A failed coup d’etat escalated the violence in May. More than 200,000 people have been displaced during the current conflict.

Nkurunziza and his ruling National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy declared a landslide victory in the country’s parliamentary and presidential polls in June. The United Nations condemned the controversial elections, saying they took place in an environment that was “not conducive for an inclusive, free and credible electoral process,” according to the Associated Press.

The predictable results have only fueled fresh violence between Nkurunziza and his opponents. The opposition, which boycotted the polls, has been accused of attacking or hounding Burundian authorities and supporters of the ruling party. Since then, dozens of people, including civilians, reportedly have been killed by Burundian authorities as well as armed opposition groups.

“There are still killings every day; a body found here, a body found there,” said Carina Tertsakian, senior researcher in the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch, a New York-based rights group. “It’s been that way for many months now and it’s not showing much sign of abating.”

Most recently, human rights groups accused police of unlawful mass killings in the bloodiest day of Burundi’s escalating crisis. Security forces loyal to Nkurunziza conducted sweeping raids and arrests in areas of Bujumbura after unidentified gunmen attacked military barracks Dec. 11. At least 300 young men were seized, with more than half of them allegedly killed and the remainder missing, the International Federation for Human Rights in Paris and the Ligue Iteka in Bujumbura said in a statement. Burundi’s military has downplayed the death toll, saying 87 people were killed and 49 were captured, according to BBC News.

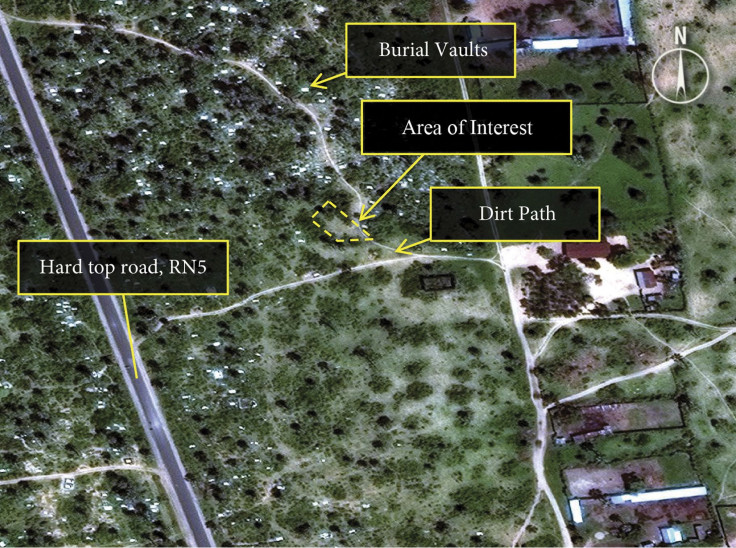

Amnesty International, a New York-based rights group, recently published satellite images that it said shows five mass graves of victims of the December massacre in Buringa, a Bujumbura suburb. “The reason these bodies were buried was to prevent us from knowing exactly how many people had been killed,” Amnesty spokeswoman Nina Walch told France 24 on Saturday.

Days after the mass killings, the African Union announced its plan to send a peacekeeping force to protect civilians and curb intensifying violence in Burundi, giving the government 96 hours to respond. An article in the African Union’s charter gives it the right to intervene in a fellow nation state “in respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.” Nkurunziza’s administration swiftly refused the deployment and said sending troops without its consent will be viewed as an attack. His government also pulled out of peace talks weeks later, saying it objected to the inclusion of opposition figures whom it deems responsible for the ongoing violence.

Following the 26th African Union summit in Ethiopia’s capital Sunday, the pan-African bloc voted to postpone dispatching troops to Burundi and opted for negotiations instead. The decision came days after a French journalist and British photographer, who were covering the ongoing crisis in Burundi, were briefly arrested in the capital during police raids.

“We want dialogue with the government of Burundi,” Smail Chergui, the African Union’s Commissioner for Peace and Security, told reporters in Addis Ababa. “The assembly has decided to send a high-level delegation to the country so they hold a dialogue.”

Political and human rights experts said the move highlighted the concerns among some African leaders, who fear that acting against a government’s wishes could set a precedent. But there are options beyond deploying soldiers. The African Union could also send human rights monitors or an international police force to patrol violence-prone areas and keep both sides in check.

“I don’t think that one initiative is the only piece to this puzzle,” said Tertsakian of Human Rights Watch.

So far, dialogue has not yielded the desired results and Nkurunziza’s defiant stance suggests the violence will not end voluntarily. The African Union’s delayed intervention could generate incentives for armed opposition groups to escalate the violence. The Burundian government may also perceive the move as a chance to crush its opponents.

“This is a real risk now, especially insofar as any escalation by the opposition is likely to provoke further violence by the government,” said Michael Broache, assistant professor of government and world affairs with a regional focus on sub-Saharan Africa at the University of Tampa in Florida.

With little hope for peace, Bujumbura resident Kavuyimbo is debating risking his life to flee his home country. Thousands of Burundians have already fled to refugee camps in Rwanda and Tanzania, but Kavuyimbo said the journey is perilous and young men accused of being dissidents have been arbitrarily detained at the borders. Many of his friends, neighbors and fellow journalists have been arrested, tortured or killed.

“I don’t expect any good answers from the African leaders,” he said in an interview Monday. “I don’t have faith in them anymore.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.